A Temple for a New Political People

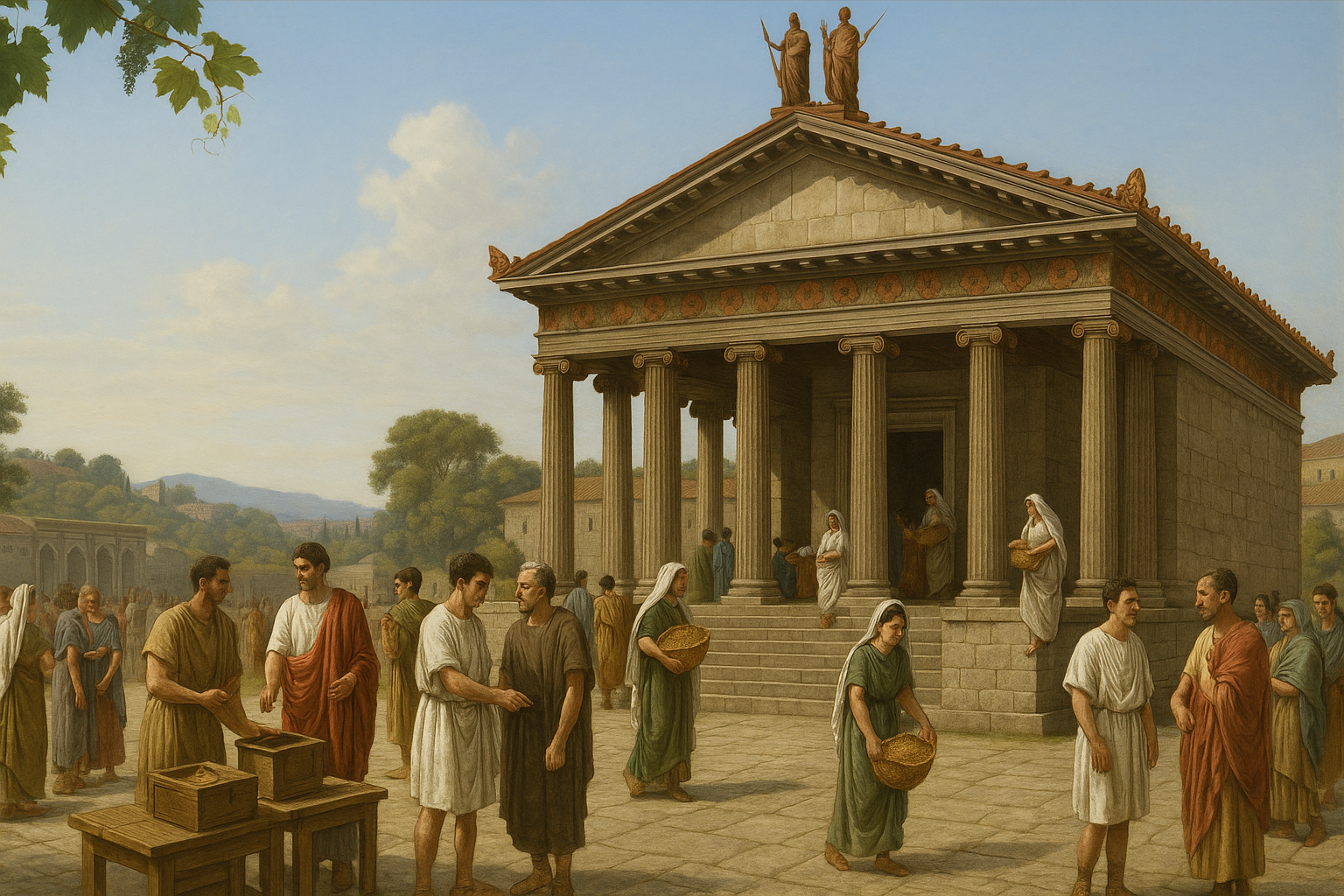

In 493 BCE, as Rome steadied itself after the fall of the kings and the first plebeian secession, a sanctuary dedicated to Ceres, Liber, and Libera rose near the southern valley of the city. The triad—grain-bearing Ceres, vine-loving Liber, and his partner Libera—was not just another addition to Rome’s sacred landscape. It became the religious and civic anchor of a new political people: the plebs. Here ritual met administration. Within sight of the Circus Maximus and the Palatine, plebeian magistrates stored records, collected fines, and staged festivals that fused identity, law, and food security. This temple did not merely serve worshippers; it gave Rome’s commoners a durable institutional home.

Why the Aventine Mattered

The Aventine’s association with the plebeians was more than topography. In early tradition, the hill was outside the patrician heartland, a liminal ridge that became a statement of belonging for those excluded from ancestral power. The sanctuary’s location—close enough to the city’s beating entertainment heart at the Circus, yet distinct from the patrician Palatine—projected a message: plebeians had a hill, a cult, and a house of records of their own. Later memory tied the Aventine to key moments in the “Struggle of the Orders,” including measures that consolidated plebeian settlement and rights on the hill. Even as scholars debate fine points of the temple’s exact site within the valley system, the Aventine remained the symbolic address of popular Rome.

The Aventine Triad: Old Gods, New Community

Rome’s choice of Ceres, Liber, and Libera reflected a deliberate blend of agrarian substance and civic symbolism. Ceres embodied grain cultivation and the social duty to feed the people; her rites emphasized order in the food supply. Liber and Libera, linked to fertility, wine, and maturation, animated the cycle from sowing to celebration. The pairing signaled more than prosperity: it mapped the life of the plebeian household—from fields and workshops to festivals—onto Rome’s sacred calendar. The triad’s rituals, processions, and public games fostered a shared identity that crossed the city’s neighborhoods and trades, creating a public culture with plebeian accents.

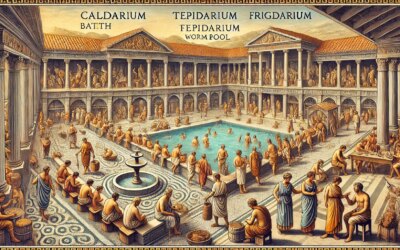

Stage and Sacred: Rome’s First Recorded Theater

When the temple was dedicated, Rome inaugurated its first recorded ludi scaenici—dramatic performances sanctioned as religious service. In a city where spectacle shaped civic life, these state-backed plays widened the audience for plebeian ritual and gave the Aventine cult a cultural reach beyond its steps. Theater did not replace sacrifice; it amplified it. Staging drama for Liber tied performance to popular festivity and helped the plebs claim Rome’s crowded public spaces as their own. The triad’s festivals would remain moments when ritual, recreation, and politics interwove.

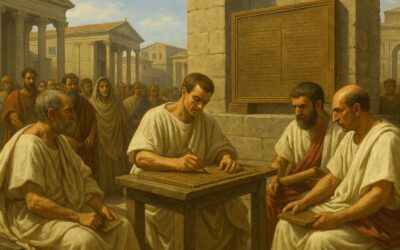

Law in a Sanctuary: Tribunes, Aediles, and the Archives

What made the Aventine triad extraordinary was not only piety but paperwork. The sanctuary functioned as a plebeian archive, administered by the plebeian aediles. Here copies of key senatorial decrees were deposited, and here fines levied by plebeian magistrates were held. In a society where control of writing and storage meant control of memory, placing records under the guardianship of plebeian officials mattered. It reduced room for patrician gatekeeping, made institutional knowledge harder to manipulate, and gave tribunes and aediles a home base from which to enforce the sacrosanct protections attached to their offices. In effect, a temple doubled as a records office and treasury—faith wrapped around files.

Grain, Justice, and the City’s Stomach

The Aventine sanctuary also touched everyday life through grain management. Ceres’ sphere encompassed the ethics and logistics of supplying the city—weights, measures, and the orderly flow of cereals into markets. As Rome expanded, the temple’s priests and associated magistrates became reference points for standards and for the public signaling that the grain year was on track. When food security frayed, ritual processions and offerings at the sanctuary proclaimed communal resolve to restore balance. The message was clear: plebeian Rome cared for the city’s stomach and would hold magistrates to account if they failed.

Greek Colors on a Roman Canvas

Architecturally and ritually, the Aventine triad bore a marked Greek flavor. The sanctuary’s early design recalled Tuscan temple forms with timber and terracotta ornament, while its cult language echoed that of Demeter and Dionysus. Far from imitation, this was a practical translation. Rome adopted what worked: a grain goddess with orderly festivals; a wine-linked pair whose rites marked youth’s passage to civic life. The result was a Roman grammar of plebeian worship that felt familiar in the Mediterranean yet spoke in the idiom of the Republic’s new politics.

From Fire to Renewal

Temple buildings are mortal. In the late first century BCE, the Aventine sanctuary suffered a devastating fire. Its reconstruction in the new imperial era retained the site’s prestige even as Rome’s skyline turned to shining marble. Ancient writers still pointed to the complex as a model of earlier building taste, a reminder that the city’s public religion had deep wooden roots beneath its later stone.

Secessions, Statutes, and the Memory of a Hill

The Aventine had long been a stage for collective action. Traditions of plebeian withdrawals from the city—moments when commoners refused to serve until their grievances were addressed—left a durable imprint on the hill’s story. Later measures concerning rights of settlement and the keeping of public decisions with plebeian officials turned custom into law and space into statute. Over time, the Aventine came to stand for a political program: that ordinary Romans could claim hillsides, festivals, courtrooms, and archives, and make them instruments of accountability.

Rituals of Freedom: The Liberalia and the Plebeian Year

Every spring the Liberalia marked personal transitions and civic belonging. Processions wound through the streets, rustic emblems reappeared in the city, and the rites of maturation acknowledged youth as future citizens. Framed by the triad’s temple, these annual rhythms stitched households into the larger plebeian fabric. In a republic that often spoke the language of the elite, the Aventine calendar gave commoners a grammar of their own.

What the Aventine Triad Changed

The Aventine sanctuary did not win the “Struggle of the Orders” by itself; no single building could. But it gave plebeian politics a place: a headquarters, a set of festivals, a chest of records, a promise to feed the city fairly, and a stage on which popular officeholders could be seen doing the work of the commons. It taught Rome that law can live in a temple and that the performance of justice—filing decrees, counting measures, paying fines—can be a sacred duty.

A Hill of Memory, A Republic of Many

Walk the southern valleys of Rome in imagination and the lesson of 493 BCE remains legible. The Aventine Triad made plebeian Rome visible, audible, and durable. It channeled harvests into markets, protests into statutes, and rituals into shared identity. By giving commoners custodianship over sacred space and civic archives, the city learned to broaden who keeps its memory. In that sense, the Aventine did not simply host a temple; it made a republic feel like the work of many.