From Flavian Need to Fiscal Innovation

In the aftermath of the Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE), Emperor Vespasian faced an empire fatigued by civil war and strained finances. To refill the treasury, he introduced a novel levy on a surprisingly lucrative commodity: urine. Collected from public latrines across Rome, urine’s ammonia-rich properties made it valuable for tanning leather, laundering garments, and several industrial uses. The tax, known formally as the vectigal urinae, exemplified Flavian pragmatism—turning everyday waste into state revenue without burdening the traditional tax base.

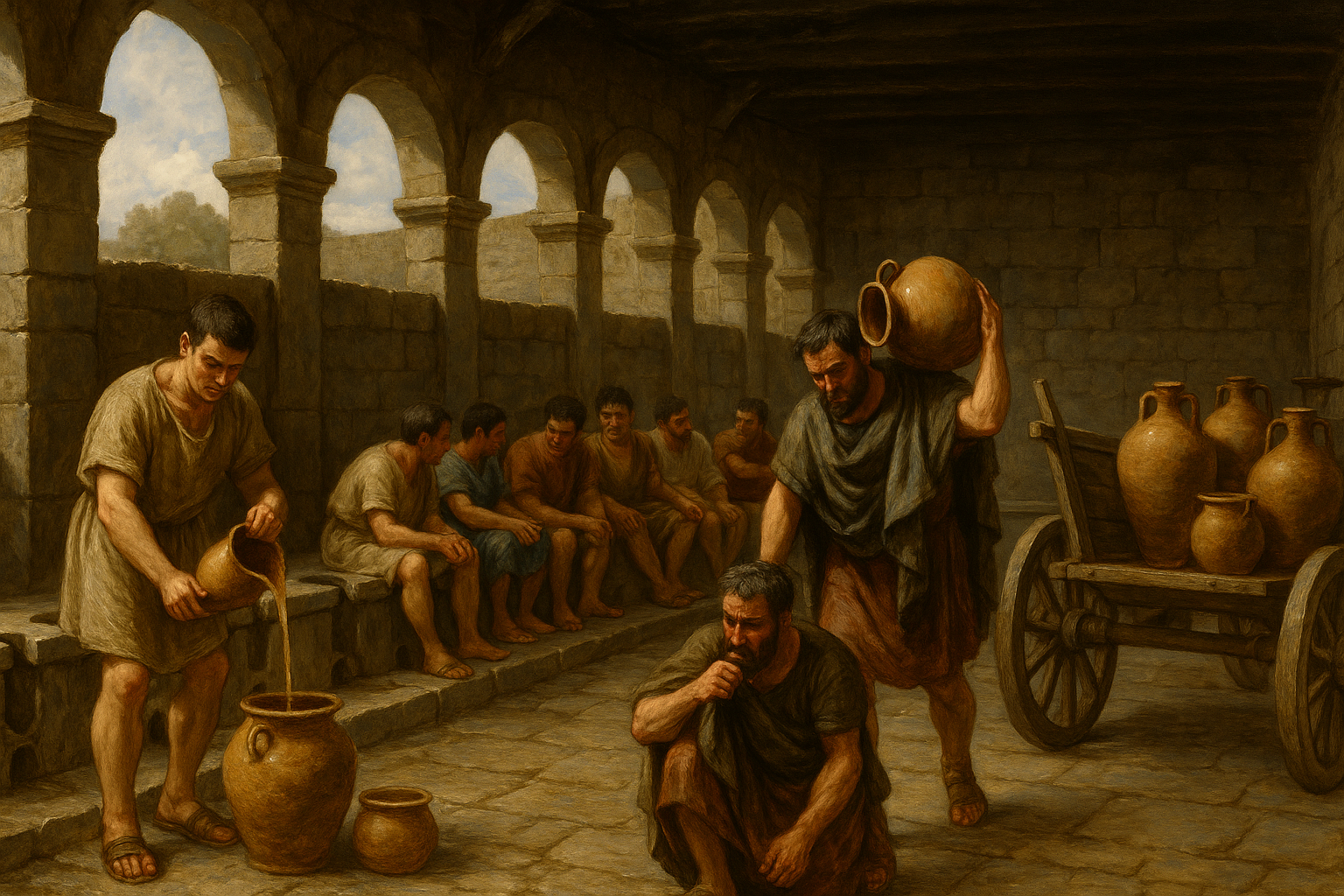

Public Latrines as Revenue Centers

Rome’s public latrines, foricae publicae, numbered over 140 sites in the capital by the late first century CE. Free access was permitted, but urine collectors—often private contractors—paid the state for the exclusive right to gather and transport it. They tapped vats beneath the benches or placed amphorae to catch the flow. The contractors bid at auction for these rights, offering a fixed annual sum to the treasury. Higher bids translated into more rigorous collection efforts. In effect, each latrine became a small-scale enterprise contributing directly to imperial coffers.

Administrative Mechanics and Oversight

The Flavian administration assigned oversight of the urine tax to officials in the aerarium militare and the fiscus. Collectors registered with local magistrates and attended auctions held in the Forum. Winning bidders received a written contract detailing the volumes and harvest points. Failure to meet quotas incurred fines or loss of franchise. While not as onerous as land or poll taxes, the urine levy demanded accuracy. Inspectors measured amphorae and audited accounts to ensure state dues were paid and collection was thorough.

Economic Ripple Effects

Shortly after Vespasian’s decree, related industries experienced shifts. Tanners and fullers—concerned about rising input costs—lobbied for exemptions or price controls. Some smaller dyers switched to alternative agents like fuller’s earth, while others consolidated their operations around sites with cheap access. The tax also generated a minor surge in amphora production, as collectors needed vessels that resisted ammonia corrosion. Local potteries near latrines adjusted their designs, reinforcing necks and using glazes to prevent damage.

Social Reactions and Moral Debates

Contemporary writers found the urine tax worthy of comment. Seneca reputedly quipped that “money does not stink,” though the attribution remains debated among scholars. Critics likened the levy to a species of moral taxation, charging citizens for an involuntary biological act. For many Romans, it was a visible sign of imperial intrusion into daily life. Yet the levy did not provoke open revolt. Its indirect nature, collected from contractors rather than private citizens directly, diffused outrage and showcased the subtlety of Roman fiscal innovation.

Legacy and Symbolism

Vespasian’s urine tax survived his reign and into the second century, testament to its efficacy. Later emperors continued to auction collection rights, occasionally adjusting rates to reflect market fluctuations. Beyond its financial role, the tax left a cultural imprint: public latrines symbolized the calculus of waste and wealth, where even the least sanitary resources could be harnessed for state power. The famous anecdote of Vespasian displaying a coin from the tax under Nero’s nose reinforced the emperor’s reputation for frugality and wit.

Why It Matters for Rome’s Fiscal System

The vectigal urinae illustrated several enduring features of Roman taxation: reliance on indirect levies, the use of public auctions to establish competitive revenue streams, and administrative precision in auditing. It demonstrated the empire’s capacity to adapt ancient systems to new economic realities without destabilizing social order. In a city teeming with inefficiencies, turning human waste into wealth was a testament to Roman ingenuity and the state’s reach.

FAQ

What exactly was Vespasian’s urine tax?

The urine tax, or vectigal urinae, was a levy on urine collected from public latrines in Rome around 70 CE. Contractors paid for exclusive rights to harvest and sell the urine, which was used in tanning, laundering, and other industries. The state benefited through fixed annual payments based on auctions and collected fines if contractors failed to meet quotas.

How did collectors bid for urine rights?

Auctions took place in the Forum under magistrates’ supervision. Collectors submitted bids for the annual lease of extraction rights at specific latrine sites. Winning bidders received contracts stating volume obligations and payment schedules. Failure to comply led to fines or revocation, ensuring collectors maintained consistent harvests and revenue flowed to the treasury.

Did ordinary Romans pay the urine tax directly?

No. Ordinary citizens did not pay the tax directly. The levy applied to contractors who gathered urine. This indirect mechanism minimized popular resentment and avoided direct charges on individuals, reflecting Rome’s preference for indirect levies that diffused social impact while securing state income.

What industries benefited from collected urine?

Tanning and fulling industries relied heavily on urine for its ammonia content, which assisted in removing fats and cleaning cloth. Laundries, dyeing workshops, and even glues and cosmetics manufacturers valued urine as a cheap chemical agent. The tax influenced production patterns, encouraging larger-scale operations near collection points.

Is Vespasian’s “money does not stink” quote authentic?

Ancient sources attribute the phrase “money does not stink” to Vespasian, but it remains debated. Some argue it reflects Flavian pragmatism rather than an exact historical utterance. Regardless, the anecdote captured the symbolic power of the urine levy and underscored the emperor’s image as a fiscal innovator unbothered by sanitary taboos.