The Foundations of Roman Learning

In the 1st century AD, at the height of the Roman Empire, education was a cornerstone of elite Roman identity. While formal schooling was not universal and remained largely reserved for the sons (and occasionally daughters) of wealthy families, the Roman education system reflected the values, ambitions, and structures of imperial society. Rooted in Greek tradition but shaped by Roman discipline and civic ideals, education aimed to produce orators, statesmen, and citizens worthy of the Republic’s legacy—even under the emperors.

Who Was Educated?

Education in Rome was a marker of class and status. While basic literacy may have been more widespread among traders and artisans, comprehensive schooling was primarily the domain of the elite. Boys from senatorial and equestrian families were groomed from an early age to lead, govern, and persuade. Girls from upper-class families sometimes received private instruction in reading, writing, and music, but rarely advanced beyond the basics unless their families were unusually progressive.

Slaves also played a crucial role in education. Many educated Greek slaves were employed as paedagogi (tutors), grammar teachers, or even philosophers within Roman households. Some freedmen opened small schools for children of modest means, especially in larger cities like Rome, Alexandria, or Antioch.

The Structure of Roman Education

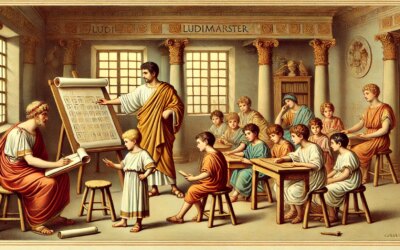

The Roman education system was divided into several distinct stages:

- Ludus litterarius: From around age 7, children attended a primary school run by a ludi magister. Here, they learned the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Wax tablets, reed pens, and scrolls were standard tools of the trade.

- Grammaticus: Around age 12, boys moved on to study with a grammaticus, who taught grammar, literature, and poetry—mostly in Latin and Greek. Students read Homer, Virgil, and other classics, analyzing syntax and themes while learning moral lessons.

- Rhetor: The final stage was instruction in rhetoric, taught by a rhetor. Reserved for the most ambitious, this stage prepared students for careers in law, politics, and public life. They practiced declamations, learned persuasive techniques, and memorized legal arguments—skills essential for the Senate or the courts.

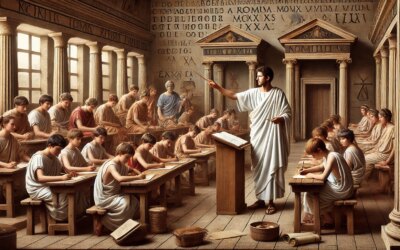

The Schoolroom Environment

Schooling often took place in modest surroundings: rented rooms, porticos, or even shaded areas of the domus (house). Students sat on benches or stools and copied texts with styluses on wax tablets. Discipline was strict; corporal punishment was common and often expected. The paedagogus accompanied children to and from school, ensuring proper behavior and reinforcing lessons at home.

Classes were usually mixed in age and ability, with instruction largely oral and repetitive. Students memorized lines, recited aloud, and copied sentences—a method that favored rote learning but built foundational skills.

Curriculum and Content

Roman education emphasized literature, language, and moral instruction. Students read Roman and Greek authors: Virgil, Horace, Cicero, and Homer. They learned history through stories, geography through myth, and ethics through maxims. Religion and mythological knowledge were woven into literary study, reinforcing cultural norms and traditional values.

Mathematics, music, and geometry were sometimes taught, especially to elite students, but never at the expense of rhetorical training. The ultimate goal was not just knowledge, but virtus—the Roman ideal of courage, character, and civic excellence.

Philosophy and Advanced Learning

For those pursuing further education, especially in the Greek East, philosophy was a natural next step. Wealthy Romans sent their sons to Athens, Rhodes, or Alexandria to study under famous philosophers of Stoicism, Epicureanism, or Platonism. The aim was to cultivate moral reasoning, ethical strength, and cosmopolitan perspective.

Philosophy remained a marker of intellectual prestige, though few Romans adopted its teachings fully. It was as much a social credential as a genuine guide to life, especially among the senatorial class.

Education and Social Control

Roman education served the state as much as the individual. By training young men to speak well, obey elders, and honor tradition, it helped reproduce the elite class and preserve Roman identity across generations. Schools reinforced hierarchy, discipline, and patriarchy, mirroring the political structure of the empire.

Yet within this system, moments of creativity and individual excellence emerged. Poets, historians, jurists, and orators all passed through these classrooms. The legacy of their training shaped not only Rome but the Western world’s future educational ideals.

The Legacy of Roman Education

The Roman model influenced medieval monastic schools, Renaissance humanism, and modern classical curricula. Its methods—memorization, recitation, commentary—persist in language and law instruction to this day. Cicero’s rhetorical techniques are still taught in debate, and Latin remains a foundation of legal and scientific terminology.

Education in 1st century Rome was far from democratic, but it laid the groundwork for intellectual continuity in a world that prized order, eloquence, and tradition. In every scroll, every speech, and every etched wax tablet, one can trace the disciplined hand of a civilization that believed learning was the key to greatness.