The Last Emperor and a Dying Empire

On May 29, 1453, the thousand-year-old Byzantine Empire came to a dramatic and violent end. As the walls of Constantinople crumbled under the relentless bombardment of Ottoman cannons, Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos, clad in imperial armor, fought and died alongside his soldiers—refusing to flee even as his capital fell. The Fall of Constantinople marked not just the collapse of Byzantium but the final breath of the Eastern Roman Empire, a direct continuation of the empire founded by Augustus in 27 BCE.

A City Under Siege

By the mid-15th century, the Byzantine Empire was a shadow of its former self—reduced to the city of Constantinople and a few scattered territories. Surrounded by the rising Ottoman Empire, led by the ambitious Sultan Mehmed II, the imperial capital stood as the last vestige of Rome in the East. In April 1453, Mehmed began his siege with an army of over 80,000 men, including elite Janissaries and formidable artillery, most notably the monstrous Basilica cannon, capable of breaching ancient walls.

Constantine XI, though commanding only about 7,000 defenders—many of them foreign mercenaries—refused to surrender. The city’s Theodosian Walls, once thought impregnable, faced a new kind of warfare powered by gunpowder and siege engineering. Over the next seven weeks, Constantinople endured relentless assault, with skirmishes, tunnel warfare, and constant bombardment taking a heavy toll.

Constantine’s Stand and Final Hours

Constantine XI was not only emperor but a warrior-leader in the Roman tradition. In the final days of the siege, he visited every section of the wall, encouraged the weary troops, and organized defenses. On the night before the final assault, he reportedly gathered his closest allies, confessed his sins, and partook in one last Christian liturgy inside the Hagia Sophia—Rome’s greatest church turned final sanctuary.

When the Ottomans breached the walls at dawn, Constantine threw off his imperial regalia and fought in the melee. His final moments are shrouded in legend. Some say his body was never found; others that he was identified by his purple boots. To many Greeks, he became the Marble Emperor, destined to return and reclaim his city—a myth that lives in folk memory even today.

The Conquest and Aftermath

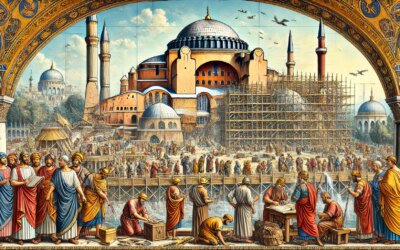

After hours of brutal street fighting, Mehmed’s forces overran the city. The Ottomans looted and killed for three days, as was customary, before Mehmed reestablished order. He rode into the Hagia Sophia and ordered its conversion into a mosque—symbolizing both conquest and continuity. He declared himself Kayser-i Rûm (Caesar of Rome), positioning the Ottoman Empire as the heir to the Roman legacy.

The fall sent shockwaves through Christian Europe. While the West had long treated Byzantium with suspicion, its final demise prompted fears of Islamic expansion and inspired a flood of refugees, scholars, and manuscripts to Italy—fueling the Renaissance. The Roman Empire, which had split in 395 CE and weathered countless invasions, was now gone. Its spiritual and intellectual legacy, however, remained embedded in European consciousness.

The Long Legacy of a Lost Empire

Constantinople was not just any city—it had been the “New Rome,” founded by Constantine the Great in 330 AD. Its fall marked the end of the medieval Christian East, the shift of power to the Ottomans, and the dawn of a new geopolitical era. For Orthodox Christians, the loss was especially painful; the Ecumenical Patriarchate would survive, but under Ottoman rule.

Yet the memory of Constantine XI endured. In Greek Orthodox tradition, he is revered as a martyr. Poems, laments, and folk songs remember his courage. His story inspired 19th-century Greek nationalists and continues to be honored by modern Byzantinists and heritage scholars. In some corners of the Orthodox world, he is even considered an unofficial saint—though never canonized.

From Ruin to Renewal

Today, Istanbul’s skyline bears the legacy of that fateful siege: minarets rising above the dome of the Hagia Sophia, once the centerpiece of Eastern Christendom. Visitors walk through the old city walls, now weathered but still majestic. Museums and mosaics recall the brilliance of Byzantine culture, even as the city pulses with Ottoman and Turkish history.

The Fall of Constantinople is more than a military event—it is a pivotal cultural and civilizational moment. It marks the end of antiquity’s last empire, the transformation of the Eastern Mediterranean, and the enduring power of a story: of an emperor who chose to fall with his city, rather than flee its fate.