Welcoming the Spirit of Spring

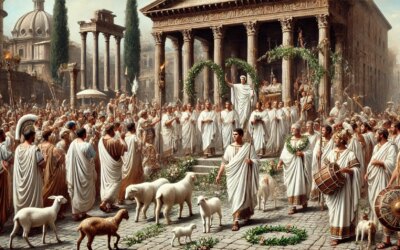

Each year between late April and early May, ancient Romans filled their streets with color, laughter, and blossoms for one of the most joyous festivals of the Roman calendar: Floralia. Honoring the goddess Flora, patron of flowers, vegetation, and fertility, the festival was a riotous celebration of spring’s renewal. In contrast to the somber and austere rites of other Roman religious observances, Floralia was marked by theatrical performances, games, and revelry that celebrated life’s beauty, sexuality, and spontaneity.

Flora: The Goddess of Blooming Life

Flora was a relatively minor deity in the Roman pantheon but held an essential role in the agricultural cycle. Associated with flowering plants, she embodied the moment when buds burst into bloom—an image that carried both literal and metaphorical fertility. Her cult was of Sabine origin and deeply rooted in Rome’s rural past, when the rhythms of agriculture governed daily life.

The Temple of Flora, located near the Circus Maximus, was built in 238 BCE following a series of unusual omens and a consultation of the Sibylline Books. From that moment, the Floralia was established as an official ludi—public games—held annually in her honor.

The Timing and Spirit of the Festival

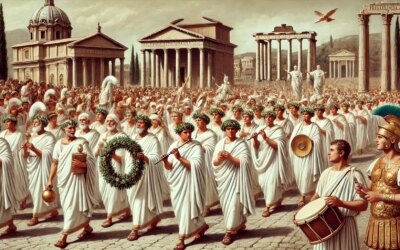

Floralia began on April 28 and ran for six days, culminating in a vivid expression of liberation and indulgence. Unlike the solemn Lemuria or Parentalia, Floralia was bawdy and theatrical—appealing to the senses and reflecting the lush abundance of spring.

Its themes of growth, fertility, and sexuality were overtly celebrated. In Roman thought, spring was the season of Eros, and Floralia embraced this with a playful and unrestrained tone. It was one of the few festivals that especially emphasized women’s participation and expression, granting them space to step outside the constraints of traditional decorum.

Celebrations in Bloom

The Roman people honored Flora with a variety of customs:

- Floral Garlands: Citizens wore brightly colored garments and adorned themselves with flower wreaths. White was replaced by vivid hues—yellow, pink, and green.

- Theatrical Performances: Comedy, mimes, and farcical plays were staged, often with risqué or erotic content. Actors performed naked or in minimal costume, drawing roars of laughter from the crowd.

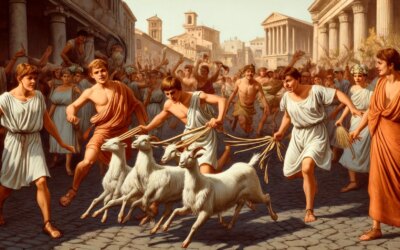

- Venationes: On one day, exotic animals such as hares, goats, and deer—symbols of fertility—were released into the Circus Maximus for games and amusement.

- Freedom of Behavior: During Floralia, norms relaxed. Prostitutes were allowed to participate openly, and women could mimic the behaviors of men—drinking in public, participating in jokes, and engaging in theatrical roles typically denied them.

The overall atmosphere was one of joyful transgression, a moment of sanctioned social inversion, not unlike Saturnalia but set in the bloom of spring rather than the depths of winter.

Floralia in the Roman Cultural Landscape

Floralia served multiple functions in Roman society. It was agricultural, reinforcing the community’s bond with the land and seasons. It was religious, venerating a deity tied to the cycle of life. And it was psychological—an annual release valve of fun and freedom before the resumption of order and duty.

The festival was also politically useful. Roman elites and emperors used it to win favor, sponsoring games and spectacles. Like other ludi, it reinforced civic unity and imperial benevolence. By the 1st century AD, emperors such as Nero and Claudius lavishly funded Floralia events to distract and entertain the masses.

Decline and Christian Rejection

As Christianity took root in the empire, festivals like Floralia drew condemnation. Their celebration of sensuality, fertility, and public licentiousness clashed with emerging Christian morality. By the 4th century, many pagan rites were suppressed or reinterpreted through Christian lenses. Floralia, with its theatrical nudity and liberation of gender roles, was particularly frowned upon.

Yet, like many ancient customs, its memory endured. The symbolic power of flowers, springtime joy, and female agency continued to ripple through art, literature, and later traditions in European cultures.

Echoes in Modern Celebration

While Floralia itself vanished with the fall of pagan Rome, echoes of it remain. Spring festivals, May Day dances, flower parades, and fertility customs in modern Europe and beyond owe much to traditions like Floralia. Even the contemporary emphasis on flowers during springtime holidays may unconsciously channel ancient Rome’s most colorful feast.

In a world that often prized austerity and hierarchy, Floralia was a bright exception—a moment when petals, pleasure, and parody took center stage. For Romans, it reminded them that joy too was sacred, and that even the gods might smile when the city bloomed.