The Warrior Emperor of the Western Empire

In an age when Rome was slowly succumbing to external threats and internal instability, Emperor Valentinian I stood as a pillar of military discipline and imperial resolve. His reign (364–375 AD) was marked by relentless campaigns against barbarian incursions and efforts to reform the increasingly fractured Roman state. But in a sudden and unexpected twist, this seasoned general met his end not on the battlefield—but in a fit of fury during a tense diplomatic exchange with Alemannic envoys along the Rhine frontier.

A Reign Defined by Defense

Valentinian I rose to power following the death of Emperor Jovian, at a time when the Roman Empire was reeling from the catastrophic loss of Emperor Julian and the humiliating peace with Persia. Elected by the military and accepted by the Senate, Valentinian took command of the Western Roman Empire, while delegating the East to his brother Valens.

He immediately set about defending the empire’s extensive frontiers, particularly along the Rhine and Danube. A career soldier with years of experience, Valentinian believed in discipline, logistical efficiency, and the importance of building and maintaining fortifications. Under his leadership, the empire constructed dozens of watchtowers, fortresses, and roads across Gaul and Pannonia—part of a vast effort to contain the rising tide of Germanic tribes.

Campaigns Against the Alemanni

The Alemanni, a confederation of Germanic tribes, posed a recurring threat to Roman Gaul. Valentinian waged several campaigns against them, securing notable victories at Scarponna (in modern Lorraine) and along the Rhine. Though the Alemanni were not entirely subdued, they had learned to treat Valentinian’s name with caution. Yet, tensions remained, and diplomacy often walked hand-in-hand with warfare.

In 375 AD, Valentinian launched a campaign in Illyricum before returning to the Rhine to settle fresh disturbances. There, near the Roman fort of Brigetio (modern Szőny, Hungary), a delegation of Alemannic envoys arrived to negotiate. What followed was a moment that Roman chroniclers would remember as both dramatic and tragic.

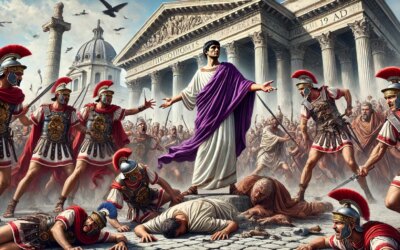

The Fatal Outburst at Brigetio

According to the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, the Alemanni approached with veiled threats, demanding favorable terms and making bold assertions. Valentinian, already ill-tempered and intolerant of barbarian arrogance, became visibly enraged. Despite warnings from his advisors, he insisted on conducting the audience in person.

As the envoys continued their demands, Valentinian lost control. He reportedly leapt to his feet, shouting, red-faced, gesturing furiously—so furious, in fact, that he suffered a fatal stroke during the exchange. The emperor collapsed and died shortly thereafter, leaving his court and commanders in stunned disarray.

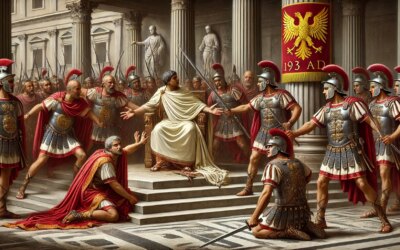

The Aftermath: An Empire in Transition

Valentinian’s sudden death created a crisis. His son, Gratian, was only 16 and had been co-emperor in name. To maintain order, the imperial court quickly elevated Valentinian’s infant son, Valentinian II, as co-Augustus in the West, creating a fragile three-way imperial structure between Gratian, Valentinian II, and Valens in the East.

The empire, though still powerful, was growing increasingly unwieldy. Valentinian’s death removed one of the last emperors with strong military credentials and a clear vision for frontier defense. His successors would soon face new waves of crises—from the Gothic Wars to the rise of Theodosius and the eventual sack of Rome itself.

Legacy of a Hard, Just Ruler

Valentinian I was not a beloved emperor. He was feared and respected. His strict rule and sometimes brutal justice earned him enemies, especially among corrupt officials and lax governors. Yet even his critics acknowledged his unwavering commitment to Roman integrity. Ammianus called him “severe but just,” a ruler who favored merit over privilege, and who prioritized the survival of the state above personal comfort or popularity.

In death, Valentinian became something of a tragic figure—a man who built walls, led armies, and kept the Western Empire intact, only to fall to his own unyielding temper. His demise was a symbol of the era: a powerful empire, still formidable, but increasingly brittle, where even an emperor could be undone not by war, but by the weight of his own rage.

The Emperor Who Died Standing

The story of Valentinian’s end at Brigetio is more than a footnote in Roman history. It is a testament to the pressures of leadership in a collapsing world, and a reminder that, for all Rome’s power, its fate was often shaped by deeply human moments—anger, pride, defiance. Valentinian I ruled with an iron hand, and in the end, it was that very force that led to his fall.