Coining Empire: Money, Authority, and Image

In a Roman workshop echoing with the clang of iron on bronze, a worker raises his hammer and strikes a die with practiced force. A moment later, a fresh coin—emblazoned with the image of the emperor—falls onto the stone floor. In the 1st century AD, the mint was not merely a place of manufacture; it was where imperial ideology met economic necessity. Coins served as currency, tools of propaganda, and tangible proof of Roman authority, flowing from the mint to every corner of the empire.

The Role of Coinage in the Roman World

Coins in ancient Rome were far more than mediums of exchange. They were announcements of power, commemorations of victories, and reminders of civic virtue. Each coin bore images and inscriptions that reinforced Rome’s political order—from portraits of emperors to symbols of the gods, military triumphs, and public works.

By the reign of Augustus, and throughout the 1st century AD, coinage had become a central tool of imperial communication, especially in provinces far from Rome. A citizen in Britannia or Syria might never see the emperor—but he would hold his likeness daily in his hand.

The Process of Minting Coins

Roman coins were made using a labor-intensive process that combined craftsmanship with bureaucratic control. The primary steps included:

- Preparation of blanks: Discs of metal, called flans or blanks, were cast or cut from metal rods and heated for malleability.

- Striking the coin: A die engraved with the coin’s reverse image was placed below the blank; the obverse die (usually the emperor’s portrait) was placed above. A mint worker struck the top die with a hammer, imprinting both sides.

- Cooling and inspection: Coins were cooled, cleaned, and examined for clarity and conformity.

While some coins were struck in large mints with multiple stations, others were produced in smaller local facilities. Quality varied depending on metal, engraver skill, and regional oversight.

The Denominations and Metals

Roman currency in the 1st century AD followed a structured system, primarily based on three metals:

- Gold (aureus): The highest value coin, used for large transactions and military payments.

- Silver (denarius): The backbone of the Roman economy, commonly used in trade and salaries.

- Bronze and copper (sestertius, dupondius, as): Everyday currency for the average Roman.

Coins were standardized in weight and content, though occasional debasement occurred—usually reflecting financial strain or imperial mismanagement. The denarius was particularly resilient, remaining dominant well into the 3rd century.

Supervision and Control

The production of coinage was tightly controlled by the Roman state. The Senate nominally oversaw bronze coins, while the emperor controlled silver and gold minting. By the mid-1st century AD, the imperial authority had eclipsed republican traditions, and coins bore titles like CAESAR, AUGUSTUS, or DIVI FILIUS.

Mints operated in key cities—Rome, Lugdunum (modern Lyon), and Antioch were prominent centers. Official engravers (signatores) and assayers (probatores) ensured consistency and guarded against forgery, a crime punished with extreme severity.

Propaganda in Metal

Roman coins were miniature billboards. Emperors used them to celebrate military victories, honor deified relatives, or promise future reforms. Typical reverse images included:

- Victory holding a wreath or palm.

- Goddesses like Roma, Fortuna, or Pax.

- Symbols of plenty like cornucopiae, altars, or ships.

- Scenes of imperial generosity: distributing grain or funding temples.

The coins of Vespasian, minted after the civil wars of 69 AD, emphasized stability and divine favor. Trajan’s coins later commemorated his conquests in Dacia. Each issue was a carefully crafted message—part history, part promise.

Circulation and Reach

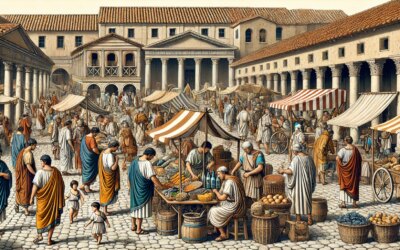

Roman coins traveled widely. Merchants, soldiers, and tax collectors spread them across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. Provincial mints sometimes included local symbols or languages, but always featured the emperor’s image, reinforcing Rome’s unifying presence.

Archaeological hoards reveal coins from multiple emperors and mints buried together, illustrating their circulation and use across generations and geographies.

Coinage and the Common Roman

To the average Roman, coins were part of everyday life—used for bread, wine, clothing, and entertainment. Their imagery influenced public perception, subtly shaping political loyalty and imperial cult practice.

Reliefs and paintings sometimes depict merchants weighing coins, or beggars holding out a hand for an as. Even graffiti in Pompeii reflects coin use—listing prices, wages, and debts. For both rich and poor, coins were the language of commerce and power.

The Legacy of Roman Coinage

Modern currencies draw heavily from Roman precedent: uniform coinage, state-minted images, and standardized denominations. Many emblems—laurel wreaths, eagles, bust profiles—have roots in Roman numismatics.

Collectors and historians study Roman coins not only for economic history, but for insights into politics, religion, art, and propaganda. Each coin remains a preserved voice of its era, struck in metal, passed from hand to hand through the centuries.

Echoes of Empire in Every Coin

In the rhythmic striking of hammers in a Roman mint, we hear the heartbeat of a civilization—one that combined order, ambition, and innovation in every detail. Coins were more than money—they were Rome’s message to its people and to history itself.