The Heart of Roman Public Life

In the bustling cities of the Roman Empire, amidst temples, markets, and forums, one structure stood out for its daily draw and cultural significance: the thermae, or Roman bathhouse. By the 2nd century AD, these establishments had become essential hubs of hygiene, health, and sociability. Far from being mere places to wash, Roman baths were architectural marvels and the beating heart of civic life.

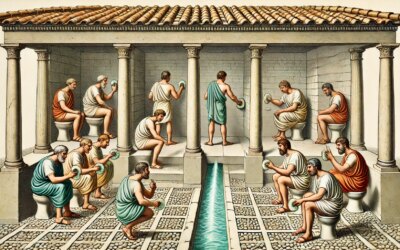

Bathing as a Social Ritual

Bathing in Rome was a daily routine for most citizens, regardless of class. While elite Romans might also have private baths at home, the public bathhouse offered more than cleanliness—it was a place to meet friends, exercise, discuss politics, and even conduct business.

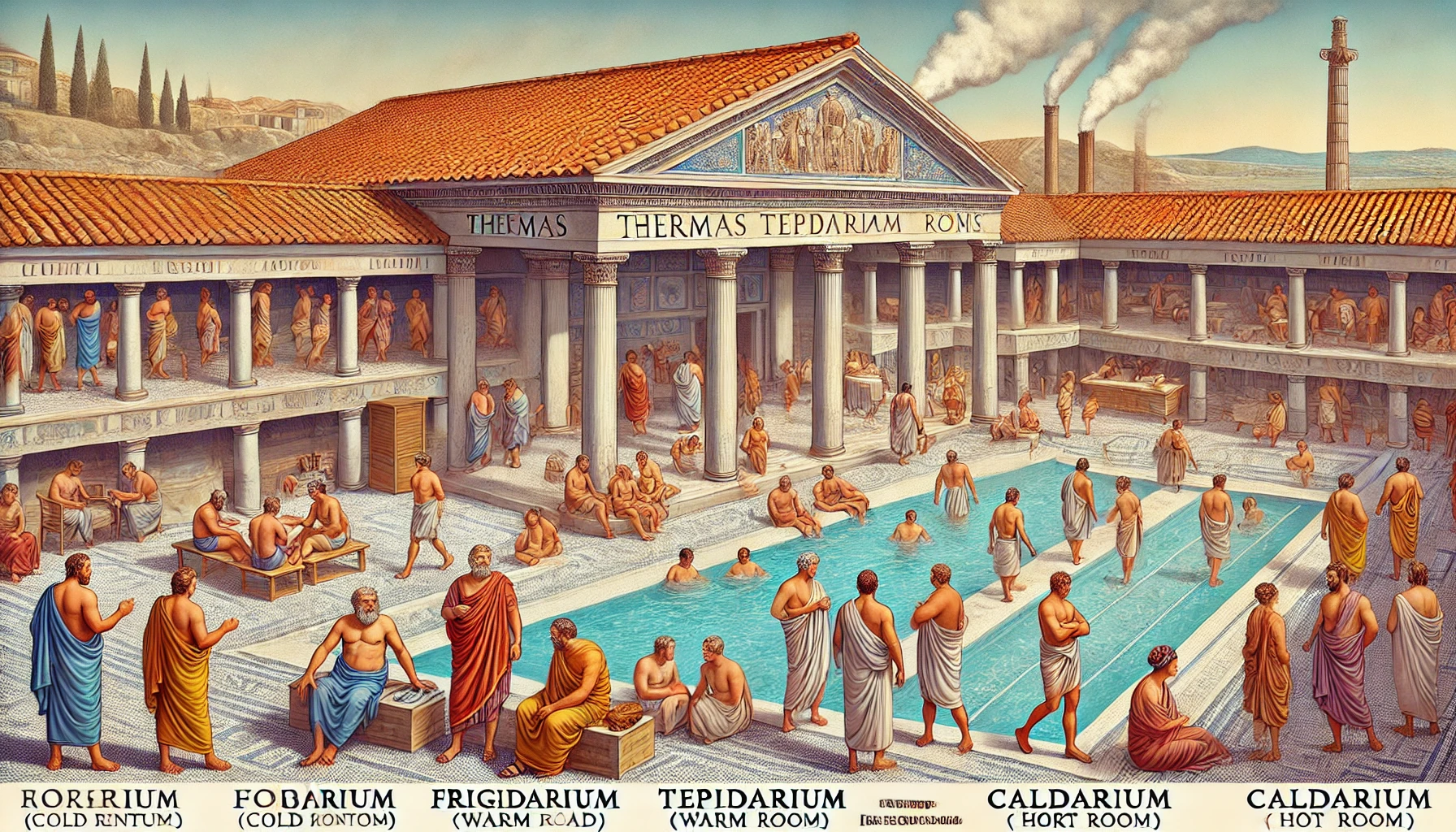

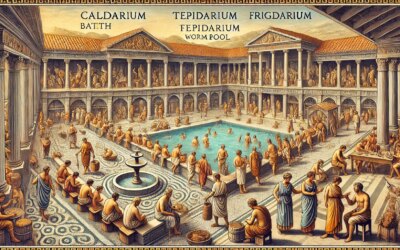

The experience followed a deliberate progression through a sequence of rooms:

- Apodyterium – The changing room, where patrons undressed and stored belongings in cubbies guarded by slaves.

- Tepidarium – A warm, relaxing room to acclimate the body.

- Caldarium – The hot, steamy room featuring a heated pool and intense humidity, often fueled by the hypocaust system beneath the floor.

- Frigidarium – A cold pool to close pores and refresh after the hot rooms.

- Palaestra – An adjacent gymnasium for exercise and sports.

Many thermae also included libraries, gardens, shops, and spaces for massage and perfuming, turning a simple bath into an immersive social experience.

Ingenious Engineering: The Hypocaust System

The bathhouses of Rome were engineering masterpieces. The cornerstone of their heating system was the hypocaust, a series of pillars and flues built beneath the floors. Heated air from furnaces (praefurnia) circulated below, warming the floors and walls. Slaves stoked these fires constantly, ensuring even heat throughout the caldarium and tepidarium.

Water came from Rome’s expansive aqueduct system. Baths like the Baths of Caracalla and Baths of Trajan could service thousands of visitors daily thanks to aqueduct-fed cisterns and massive underground reservoirs.

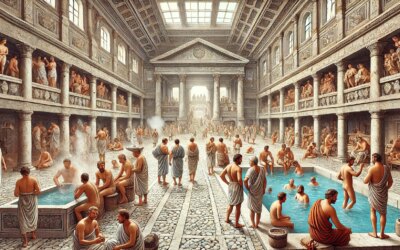

Architecture and Aesthetics

Thermae were grand and often monumental in design. Vaulted ceilings, mosaic floors, marble-clad walls, and statues of gods and emperors created an atmosphere of opulence. Domes and clerestory windows allowed light to flood the space, enhancing the sense of splendor and sacred ritual.

In the 2nd century AD, emperors saw bathhouses as expressions of imperial benevolence and Roman superiority. Building them not only provided public service but also eternalized their names in the urban fabric of Rome and its provinces.

Baths for Everyone

While some elite baths required a fee or offered private suites, most bathhouses were accessible to common citizens. A small entry fee—often just a few asses—was waived on holidays or paid by wealthy patrons. Separate hours or entrances were designated for men and women, though mixed bathing did occur, especially in less formal settings.

Bathing was an egalitarian experience—soldiers, merchants, slaves, and senators could all be found within the same steam-filled walls. The rituals of scrubbing, oiling, and relaxing served as a daily equalizer.

The Bathing Process

Patrons began by exercising in the palaestra, working up a sweat. They then moved through the warm rooms to the caldarium, where oil and strigils were used to cleanse the skin. Soap was rare; olive oil applied and then scraped off with curved metal tools served to remove dirt and dead skin.

After enduring the heat, bathers would plunge into the frigidarium, refreshing themselves and stimulating circulation. Massage, hair removal, and perfuming followed, before patrons redressed and returned to their lives.

Hygiene and Health

Despite their social nature, Roman baths were also about health. Physicians recommended regular bathing to prevent illness, improve digestion, and promote mental clarity. The baths’ steam and thermal therapies prefigured modern spa practices, and their cleanliness—compared to other ancient societies—was notable.

However, critics like Seneca occasionally warned of moral laxity and noise in the thermae. Yet even the most austere philosophers rarely abstained entirely from their use.

Provincial Baths and Romanization

Bathhouses were not limited to Rome. In Britain, Gaul, North Africa, and the Levant, provincial thermae adopted local designs while adhering to Roman standards. These structures became symbols of Romanization, introducing conquered peoples to imperial customs, language, and lifestyle.

In cities like Bath (Aquae Sulis), Nîmes (Nemausus), and Jerash (Gerasa), bathhouses blended local elements with Roman engineering, cementing their role as cultural and civic anchors.

The Decline and Legacy

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, many thermae fell into disrepair. Aqueducts ceased operation, and heating systems were lost. In the East, Byzantine baths persisted, but gradually gave way to Islamic and Christian bathing traditions.

Today, the ruins of thermae—like those in Rome, Pompeii, and Trier—continue to awe visitors. Their design and function influenced medieval bathhouses and modern wellness spas alike. The spirit of communal hygiene and relaxation lives on in Turkish baths, European spa towns, and health resorts across the world.

Steam, Stone, and Civilization

More than architectural wonders, Roman baths were daily rituals of purification, unity, and vitality. They encapsulated the Roman ethos of public service, innovation, and pleasure. In their echoes, we find the enduring heartbeat of an empire that made hygiene a civic art and community a daily habit.