Medicine by Mortar and Scroll

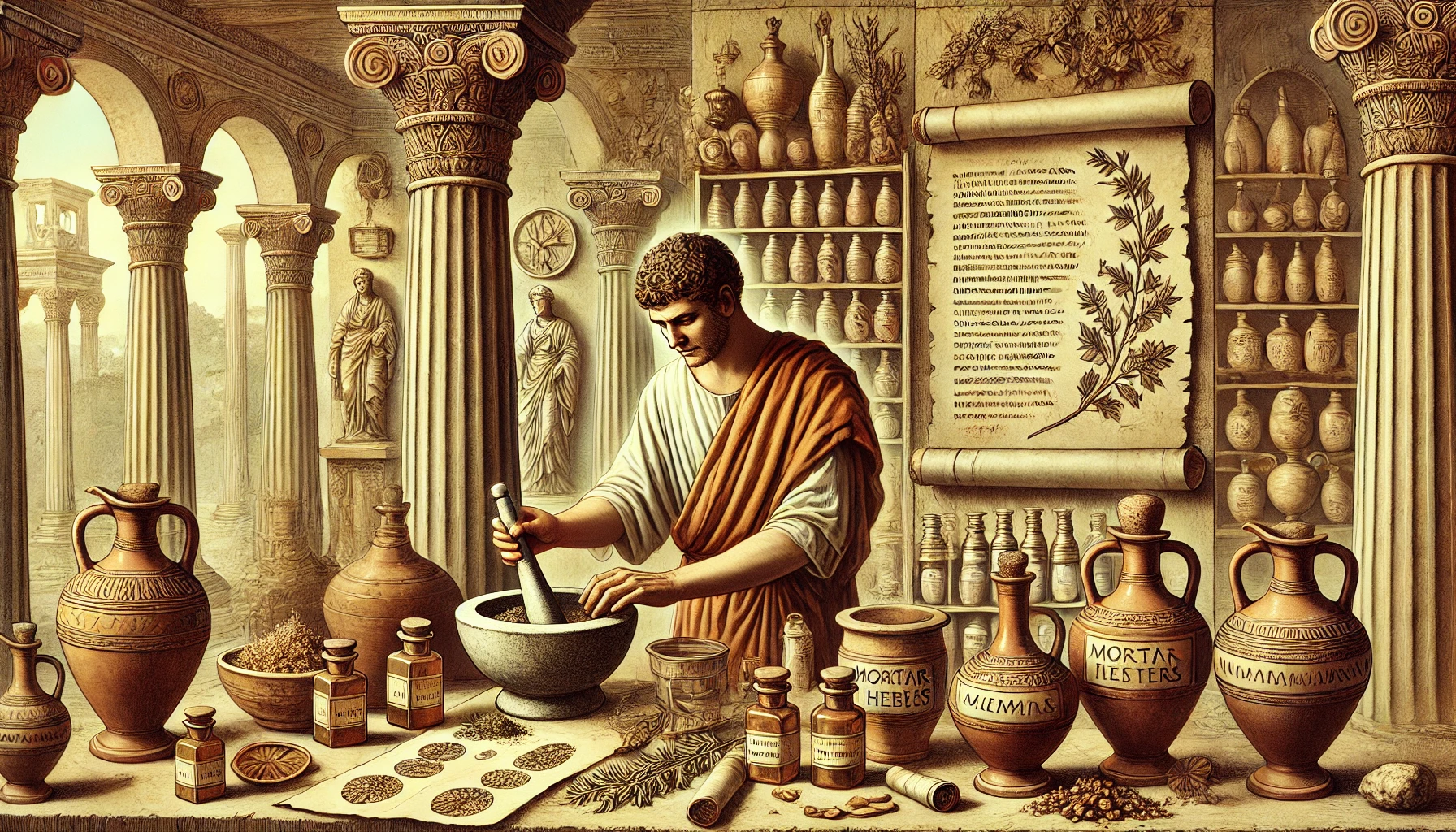

In the flickering lamplight of a Roman workshop, the scent of rosemary and myrrh lingers in the air. A man in a linen tunic leans over a marble counter, grinding herbs with a mortar and pestle, surrounded by amphorae, clay jars, and scrolls scrawled with recipes. This is the Roman apothecary—part scientist, part healer, and an essential figure in the empire’s health and medicine of the 1st century AD.

The Origins of Roman Pharmacology

Roman medicine drew heavily on Greek foundations, particularly the writings of Hippocrates and Dioscorides. By the early imperial period, the Roman world had developed a vast pharmacopoeia combining herbal remedies, animal products, minerals, and ritual elements. The apothecary, or pharmacopola, was the figure who transformed these raw materials into effective treatments.

While some medicines were compounded by physicians themselves, specialized apothecaries emerged in cities and military camps, offering ready-made remedies for everything from indigestion to snakebite.

The Apothecary’s Shop

A typical Roman apothecary operated from a street-facing shop or the rear room of a physician’s domus. Inside, shelves lined with ceramic jars, bundles of dried herbs, oils, resins, and powders were carefully labeled. Scrolls and codices provided medicinal recipes and dosage instructions, often copied from authors like Dioscorides, whose work De Materia Medica became a cornerstone of ancient pharmacology.

Tools included:

- Mortars and pestles for grinding ingredients.

- Measuring scales for precise dosages.

- Strainers, ladles, and crucibles for mixing and heating.

- Glass vessels and terracotta flasks for storing tinctures and infusions.

Common Remedies and Ingredients

Roman apothecaries relied on a mix of botanical, zoological, and mineral substances. Their knowledge came from centuries of observation, experimentation, and cultural exchange. Popular remedies included:

- Willow bark for pain relief (a precursor to aspirin).

- Garlic as an antibiotic and circulatory aid.

- Opium poppy to ease severe pain and induce sleep.

- Honey and vinegar to clean wounds.

- Wormwood and mint for digestive issues.

- Lead compounds—dangerously used in cosmetics and ointments, despite their toxicity.

Many treatments were infused with religious or superstitious elements. Charms, incantations, and offerings to healing deities like Aesculapius or Salus were often part of the prescription.

Apothecaries and Physicians

The relationship between Roman apothecaries and physicians (medici) was complex. Some worked closely together, with the apothecary preparing the physician’s orders. Others operated independently, offering over-the-counter solutions for common ailments. In large cities, elite physicians might maintain in-house apothecaries, while rural areas relied on traveling herbalists and healers.

Though considered artisans rather than scholars, many apothecaries were well-educated in botany and chemistry. Their libraries often included Greek medical treatises, Roman compilations, and personal notes passed from teacher to apprentice.

Medicine and Empire

Rome’s expansive trade networks brought exotic ingredients from across the empire—Egyptian resins, Arabian myrrh, Gallic herbs, and African minerals. Apothecaries played a role in maintaining public health in military garrisons, urban centers, and rural villas alike.

In army camps, especially, their work was vital. Roman military medicine was surprisingly advanced, and soldiers received treatments for wounds, infections, and fatigue. Apothecaries might accompany troops or be stationed at valetudinaria (military hospitals).

Women in Medicine

Although male apothecaries were more visible, women were active as herbalists, midwives, and domestic healers. Some inscriptions identify female apothecaries, and literary sources refer to women preparing salves, perfumes, and contraceptives. In elite homes, women often learned medicinal recipes passed down through generations, blending care with culinary and spiritual practices.

The Legacy of Roman Apothecaries

The practices of Roman apothecaries deeply influenced medieval and Renaissance pharmacology. Their recipes were copied into monastic herbals, Islamic medical texts, and early modern dispensaries. The concept of compounded medicines, the standardization of ingredients, and the use of pharmacopoeias all trace their roots to Roman innovation.

Artifacts—glass bottles, measuring scales, mortars, and preserved herbs—unearthed in Pompeii and other Roman towns offer a vivid picture of the ancient apothecary’s world.

Healers in the Shadows

The Roman apothecary worked in a space between science, tradition, and commerce. Part healer, part craftsman, and part philosopher, he offered solace to the sick and insight into the natural world. In his scrolls and salves lay the knowledge of generations—and the hope of a cure in an age where illness was often a mystery. Though his name may not have echoed through forums or temples, his presence was felt in every home, every army, and every life touched by the quiet, persistent pursuit of healing.