Masters of Sea and Steel

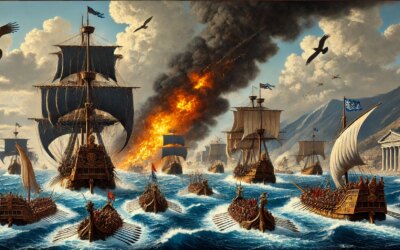

Amid the roar of crashing waves and the clang of iron against wood, the fate of empires was decided not just on land but on the open sea. In the 1st century BC, the Mediterranean—Rome’s Mare Nostrum—was a stage for intense maritime conflict. With its fleet of triremes and seasoned marines, the Roman Republic waged decisive naval battles to secure trade routes, crush pirates, and outmaneuver political rivals in civil wars that reshaped the ancient world.

The Rise of Roman Naval Power

Though Rome had long been dominant on land, its navy was relatively modest until the Punic Wars in the 3rd century BC. By the 1st century BC, however, the Republic had transformed into a formidable maritime force. As civil wars erupted and Mediterranean piracy surged, naval supremacy became essential for survival and expansion.

The Roman fleet was organized under the authority of consuls, praetors, and eventually triumvirs like Pompey, Caesar, and Octavian. Commanders employed aggressive tactics—boarding, ramming, and fire-based assaults—to subdue enemies at sea.

Roman Warships and Technology

Roman warships were based on Greek models but adapted for Roman military needs. The most common vessels during this era included:

- Triremes: Three rows of oars on each side, designed for speed and maneuverability.

- Quadriremes and quinqueremes: Heavier, more powerful ships with multiple oar arrangements and larger crews.

- Liburnians: Fast, light ships borrowed from Illyrian pirates and perfect for anti-piracy operations.

Key innovations included the corvus—a boarding device that allowed Roman soldiers to storm enemy decks—and reinforced rams used to puncture hulls. Ships were equipped with ballistae and catapults for ranged combat.

The Campaign Against the Pirates

In 67 BC, the Mediterranean faced a crisis: rampant piracy disrupted trade, captured citizens for ransom, and embarrassed Roman authority. The Senate granted Pompey Magnus extraordinary powers to clear the seas in what became a brilliant campaign.

Pompey divided the sea into regions, assigning fleets to each. In just three months, he destroyed over 1,300 pirate ships, captured or killed thousands of pirates, and resettled survivors in inland towns. His success restored Rome’s control of the sea and elevated his status to near-legendary proportions.

Naval Warfare in the Civil Wars

The latter half of the 1st century BC saw Rome’s greatest naval conflicts—not against foreign enemies, but between Romans themselves. Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BC ignited a civil war where sea power proved crucial.

Caesar’s fleet faced initial defeats but gradually adapted. In 47 BC, at the Battle of Thapsus, he used naval superiority to blockade his enemies. Later, the confrontation between Octavian and Mark Antony culminated in the monumental Battle of Actium in 31 BC, a turning point in Roman history.

At Actium, Octavian’s fleet, led by the skilled Admiral Agrippa, outmaneuvered Antony and Cleopatra’s larger ships using lighter Liburnians and superior tactics. Their defeat secured Octavian’s rise as Augustus, the first Roman emperor.

Life Aboard a Roman Warship

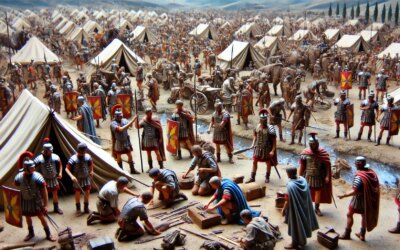

A Roman naval crew included rowers, marines, officers, and support personnel. Rowers were often free men or slaves trained in synchronized movement. Marines—heavily armed infantry—boarded enemy vessels and fought hand-to-hand.

Life at sea was brutal. Conditions were cramped, rations spartan, and morale dependent on victory and loot. Still, service in the fleet offered status, spoils, and occasionally Roman citizenship.

Ports and Naval Infrastructure

Rome supported its fleet with an expansive network of naval bases. Portus Ostia, Misenum, and Ravenna were major harbors, equipped with dry docks, arsenals, and training facilities. Engineers constructed lighthouses, warehouses, and grain depots, ensuring the fleet could operate year-round.

These bases also served political functions, projecting Roman strength across the sea and deterring rebellion in distant provinces.

Symbolism and Power

Naval imagery was prominent in Roman coinage, art, and triumphal processions. Naval victories were celebrated with crowns made of ship beaks (corona navalis) and monumental sculptures like the Navalia in Rome.

Command of the sea was not just military—it was symbolic. It meant Rome controlled trade, wealth, and destiny itself.

Legacy of Rome’s Naval Might

Though often overshadowed by legions, the Roman navy was essential to empire-building. It protected grain routes from Egypt, secured provincial coasts, and enabled fast troop movements across vast territories.

Rome’s naval architecture, strategy, and logistics would influence Byzantine, Islamic, and European navies for centuries. The Mediterranean remained, for much of history, a Roman lake in spirit if not in name.

Warriors on Water

From the Aegean to the Atlantic, the oars of Roman warships carved Rome’s legacy into the waves. Their captains commanded not just ships, but empires. In every sail raised, every ram launched, and every soldier who leapt aboard an enemy vessel, the power of Rome surged forward—an empire not only of land, but of sea.