Vows Beneath the Gods

In the flickering light of oil lamps and the fragrance of floral garlands, a Roman bride draped in a saffron veil stood before the family altar. Her hand was joined with that of the groom, and before the gathered witnesses and divine statues, they offered a panis farreus—a sacred spelt cake symbolizing unity and sacrifice. In the 1st century AD, Roman weddings were complex fusions of religious rite, legal formality, and social performance, binding not just two individuals, but families, fortunes, and legacies.

The Meaning of Roman Marriage

Marriage in ancient Rome was not primarily a matter of romance, but a public declaration of alliance. Known as matrimonium, it marked the lawful union of man and woman for the purpose of producing legitimate heirs and consolidating family power. The institution was deeply woven into Roman law and politics.

There were two principal forms of Roman marriage:

- Confarreatio: A patrician ceremony with sacred overtones, involving a priest and offerings to Jupiter.

- Usus or coemptio: Simpler forms practiced by plebeians or those without priestly sanction, often more contractual in nature.

The Betrothal and Preparations

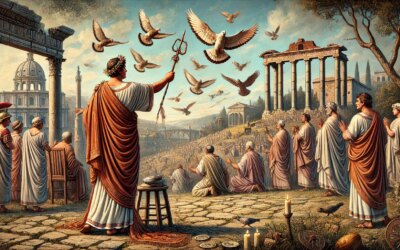

Marriage began with a betrothal (sponsalia), often arranged by the father or guardian of the bride. Contracts were drawn up, dowries negotiated, and auspices taken to ensure divine favor. Astrology and omens played a role in selecting auspicious dates.

In the days leading up to the wedding, the bride was guided by female relatives and prepared in body and spirit. Her bridal gown, usually white, was cinched with a special knot only the groom could untie, and her flammeum—a bright yellow-orange veil—marked her as a woman leaving girlhood behind.

The Ceremony and Rituals

The wedding day itself began with religious sacrifices and prayers. At the home of the bride, the couple stood before a household altar, flanked by priests and family members. A sheep or pig might be sacrificed to secure favor from the gods, particularly Juno, Venus, and Hymen.

The central act involved the joining of hands (dextrarum iunctio) and the offering of the panis farreus, made from ancient grain sacred to Rome. This symbolized unity, fertility, and the communal aspect of marriage.

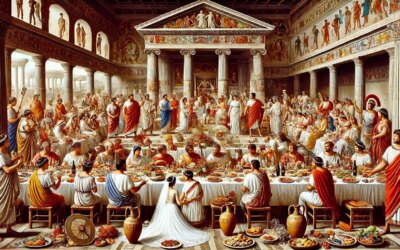

Guests and Witnesses

Weddings were attended by family, friends, and neighbors, all of whom served as social validators of the union. Elaborate banquets followed, with entertainment, music, and toasts. Guests brought symbolic gifts, such as lamps for prosperity or miniature figures for fertility.

Music was often provided by flutists and lyre players. Girls sang traditional nuptial songs, and at times, theatrical performances were included—especially in aristocratic homes where the marriage doubled as a political celebration.

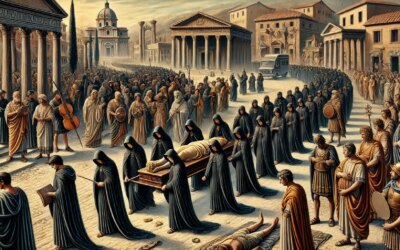

The Procession to the Groom’s House

Following the ceremony, the bride was escorted to her new home in a formal procession. She was led through the streets by torchlight, flanked by boys with laurel branches and accompanied by the chanting of Hymen!—a call to the god of weddings.

At the groom’s door, the bride was lifted over the threshold to avoid stumbling—a bad omen. She then anointed the doorposts with oil and wool, symbolizing her roles as nurturer and protector of the household.

Women and Marriage in Roman Society

For Roman women, marriage marked a major transition. Under manus (legal authority), she might pass from the control of her father to that of her husband. However, by the 1st century AD, many upper-class women retained property rights and independence through free marriage (sine manu), a reflection of evolving social norms.

Despite these freedoms, women were still expected to fulfill roles of chastity, fidelity, and domestic stewardship. Matrons like Livia Drusilla set models for ideal Roman wives—dignified, loyal, and influential within the home.

Marriage, Law, and Citizenship

Marriage also had legal ramifications. Only lawful unions between Roman citizens conferred legitimate offspring and inheritance rights. Marriages with foreigners, slaves, or persons of dishonor could be denied legal standing.

Emperors issued legislation regulating marriage. Augustus, for instance, passed the Lex Julia and Lex Papia Poppaea to encourage childbirth and penalize celibacy. These laws reflected the Roman view of marriage as a civic duty—not just a private choice.

Divorce and Dissolution

Roman marriages could end through divorce, often initiated by mutual consent or dissatisfaction. No formal court was needed—simple declarations sufficed. Dowries were typically returned, and children remained with the father. While divorce carried some stigma, it was common and accepted among Rome’s elite.

Some famous Roman figures, like Cicero and Caesar, divorced multiple times for political or personal reasons. Women, too, could seek divorce, especially if they brought wealth or influence to the table.

More Than a Union

A Roman wedding was not merely a romantic occasion—it was a civic and religious act, steeped in tradition, expectation, and social consequence. In every veil lifted, every hand clasped, and every ritual cake shared, the Romans wove their identity as a people of order, legacy, and divine favor. The echo of these ceremonies still resonates in modern rites, where vows and veils continue to mark the ancient, sacred journey from two lives into one.