The Lifeblood of an Empire

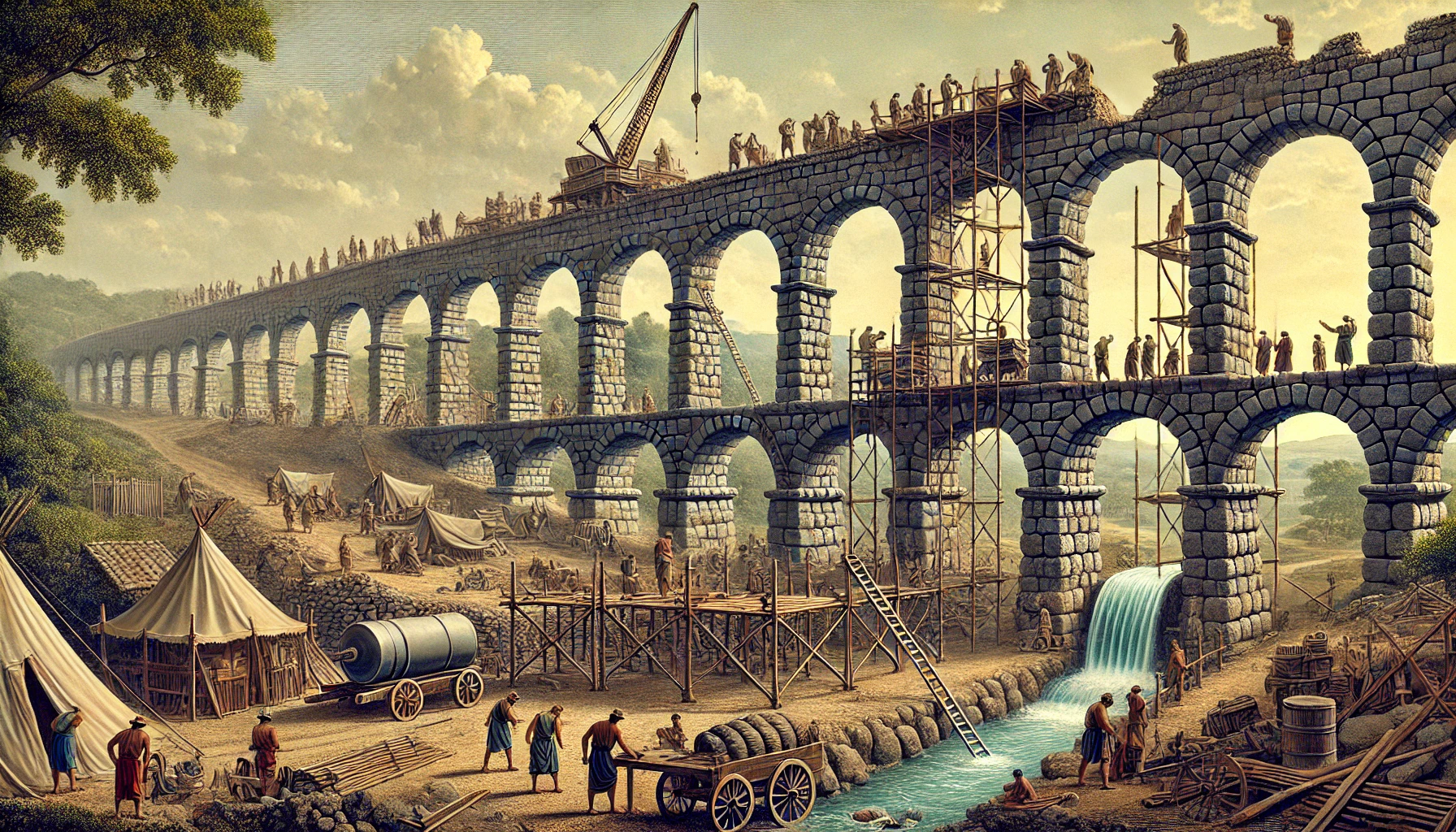

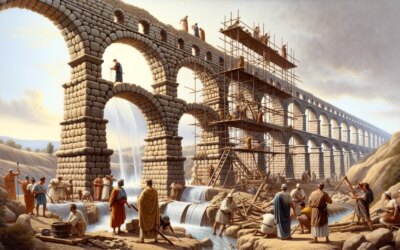

In the dust of a Roman countryside, the sound of chisels and shouted orders echoes under the Mediterranean sun. Arched structures rise slowly from scaffolding as teams of laborers, engineers, and slaves hoist stones into place. This is not a temple nor a fortress—it is the construction of a Roman aqueduct in the 1st century AD. Behind these massive stone veins lies a civilization’s ambition to channel water, tame nature, and nourish its cities with engineering genius.

Why Aqueducts Mattered

Rome’s meteoric growth brought pressing demands for water—clean, abundant, and reliable. Springs and rivers near the city were quickly exhausted. The solution? Transport water from distant sources, across hills and valleys, using gravity alone. Aqueducts were not only utilitarian; they were symbols of Roman order and urban superiority.

By the 1st century AD, the Roman capital alone was supplied by 11 aqueducts stretching over 500 kilometers combined, delivering up to 1 million cubic meters of water daily—enough for baths, fountains, households, and industrial use.

The Genius of Roman Design

Roman aqueducts were marvels of gravity-driven hydraulics. Water flowed along channels (specus) with precise gradients—typically less than 1%. Engineers carefully calculated elevation changes to maintain steady flow without stagnation or erosion.

Key structural elements included:

- Arches: Allowed aqueducts to span valleys while maintaining elevation

- Arcades: Long rows of stacked arches for stability and visibility

- Covered channels: Protected water from contamination and evaporation

- Settling tanks (castella): Removed debris and regulated flow

- Lead or ceramic pipes: Used in pressurized sections

The Builders Behind the Arches

Building an aqueduct was a monumental endeavor. The workforce included:

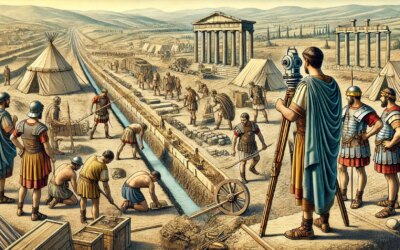

- Architecti and surveyors: Planned routes using instruments like the chorobates and dioptra

- Engineers: Oversaw materials, logistics, and site management

- Skilled laborers: Stonemasons, carpenters, and crane operators

- Manual workers and slaves: Hauled stone, mixed mortar, and cleared earth

Stone was quarried locally when possible, and wooden cranes powered by treadwheels or animal labor lifted blocks into place. Lime mortar ensured durability, and opus caementicium (Roman concrete) allowed underwater construction for tunnels and foundations.

Notable Aqueduct Projects

Some of the most renowned aqueducts constructed or expanded in the 1st century AD include:

- Aqua Claudia (started by Caligula, completed by Claudius): 69 km long, supplying the Palatine Hill

- Aqua Anio Novus: Transported water from over 80 km away, built concurrently with Aqua Claudia

- Pont du Gard (southern Gaul): A triple-tiered aqueduct bridge over the Gardon River, supplying Nemausus (Nîmes)

- Aqueduct of Segovia: One of the best-preserved, stretching over 800 meters through the Spanish city

These projects combined mathematical precision, logistical planning, and architectural flair, setting a standard for centuries to come.

The Urban Impact

In Rome, aqueducts fed public baths, ornamental fountains, and latrines. Water enabled the hygiene, leisure, and cleanliness that distinguished Roman urban life. The Baths of Agrippa, Nero, and later Caracalla depended on consistent water flow to operate at full scale.

Residents could tap into the supply—legally through registered access or illicitly via unauthorized diversions. Pliny the Elder praised aqueducts as among the most remarkable Roman achievements, while Frontinus, a 1st-century water commissioner, compiled detailed reports on water management and corruption control.

Challenges and Maintenance

Keeping aqueducts functional required vigilance. Lime scale (calcium deposits) narrowed channels over time. Roots, rodents, and sabotage posed risks. Specialized crews of aquarii and curatores aquarum inspected, cleaned, and repaired damage constantly.

Protective laws prohibited construction near aqueduct paths. The penalty for tampering could be severe—fines, confiscation, or worse. Despite these efforts, water theft remained widespread.

The Decline and Echoes of Innovation

With the decline of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD, maintenance collapsed. Many aqueducts fell into disrepair or were deliberately destroyed during sieges. Cities returned to wells and rivers, and the level of urban life declined.

Yet the legacy endured. Medieval architects marveled at surviving aqueducts, and Renaissance engineers, inspired by Roman models, revived hydraulic planning. Modern water systems owe much to the principles pioneered by Rome’s aqueduct engineers.

Monuments of Movement

To stand beneath a Roman aqueduct is to witness the ambition and ability of a civilization that mastered water and stone. These constructions were not only feats of engineering—they were declarations of control, permanence, and care for the urban populace.

They remain among the greatest gifts ancient Rome bequeathed to the modern world: silent, soaring reminders that to supply water is to sustain life—and to do so on an imperial scale is nothing short of genius.