Medicine at the Crossroads of Reason and Ritual

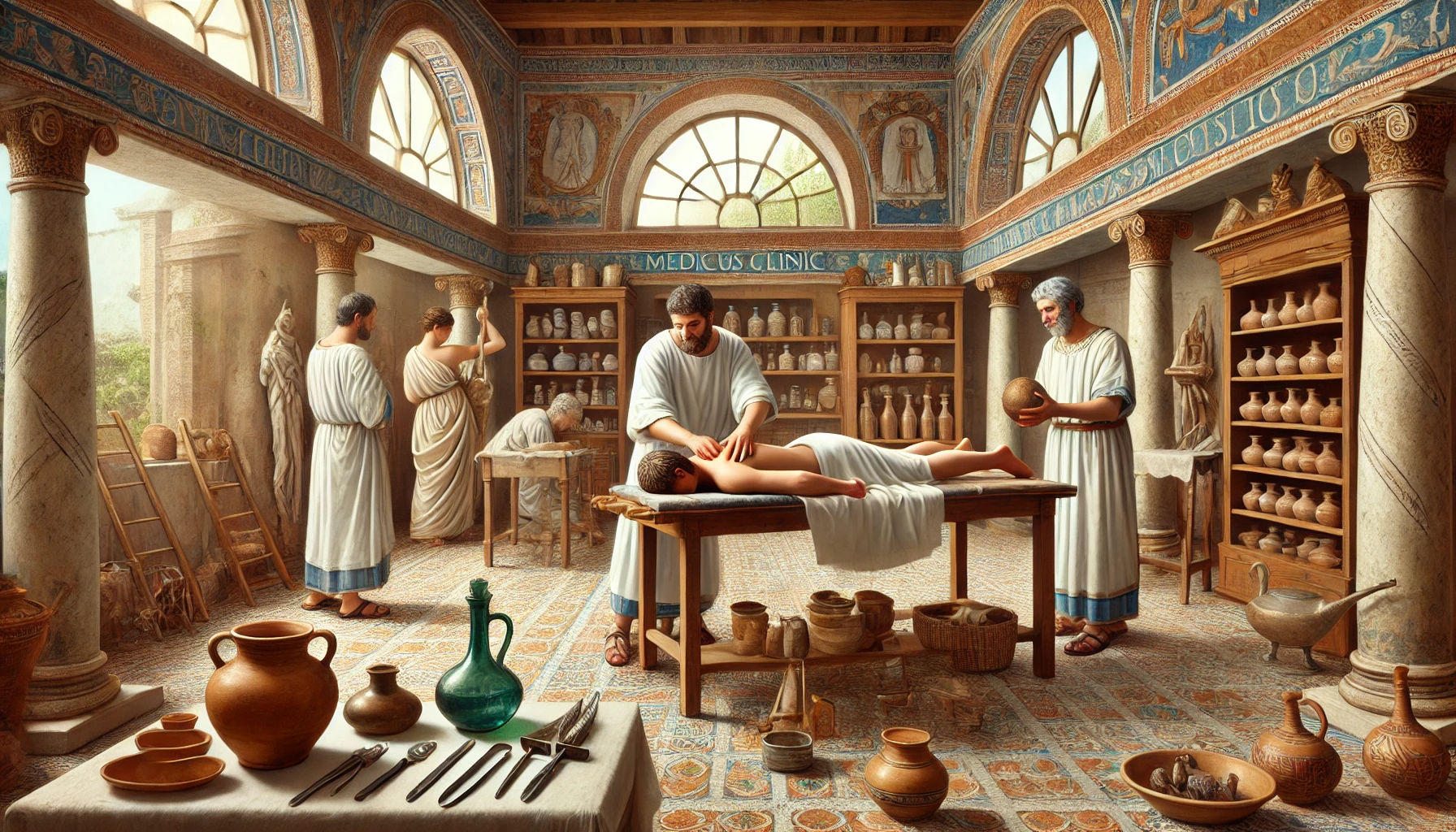

In a modest stone building near the heart of a Roman town, a man lies on a wooden table. A physician inspects a wound, his assistant grinding herbs in a bronze mortar. Surgical tools are arranged with care on a linen cloth—scalpels, forceps, bone hooks. This is a Roman medical clinic in the 1st century AD—a place where empirical observation met inherited superstition, and the body became the terrain of Roman intellect and ingenuity.

Who Was the Roman Medicus?

The medicus, or Roman doctor, occupied a complex social role. Some were highly educated professionals trained in Alexandria or Pergamum, while others were former slaves, soldiers, or self-taught healers. Despite this diversity, medicine was regarded as a respected and essential craft, especially in urban centers and military camps.

Physicians treated everything from infections and injuries to childbirth, mental illness, and chronic pain. While not licensed in a modern sense, many were affiliated with guilds or sponsored by wealthy patrons. Some became famous across the empire, such as Galen of Pergamum, whose theories shaped Western medicine for centuries.

The Roman Medical Clinic

Most clinics were private domus-based spaces, although public facilities also existed in larger towns. A typical clinic included:

- Examination area with a wooden or stone table

- Shelves of jars and phials containing herbs, resins, and powders

- Tool chests with scalpels, probes, forceps, specula, and cautery irons

- Writing tablets and styluses for prescriptions and case notes

- Decorative frescoes or statuettes invoking gods of healing

Lighting was provided by oil lamps, and ventilation came through arched windows or open courtyards. Hygiene varied, but military clinics (valetudinaria) in legionary forts were among the cleanest medical spaces of the ancient world.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Roman physicians relied on observation, patient history, and manual examination. They felt pulses, examined urine, and listened to symptoms. While they lacked germ theory, they developed a sophisticated understanding of bodily systems, especially under the influence of Greek medicine.

Common treatments included:

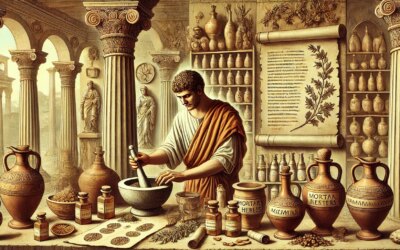

- Herbal remedies: Mint, garlic, rue, poppy, and myrrh

- Diet and regimen: Controlled food intake, baths, and exercise

- Surgical procedures: Removal of tumors, bloodletting, bone setting

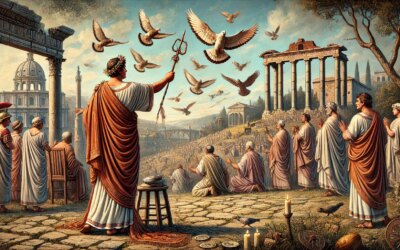

- Magical and religious cures: Amulets, incantations, and offerings to Asclepius

Patients were often instructed to visit baths, take prescribed walks, and avoid certain foods or behaviors. Though rudimentary, many treatments had practical therapeutic value.

Military Medicine and Innovation

The Roman army was a major driver of medical advancement. Each legion had a dedicated valetudinarium (field hospital), staffed by medici, assistants, and orderlies. These clinics were well-organized, with specialized rooms for surgery, recovery, and storage.

Roman military doctors became skilled in trauma care, wound dressing, and amputation, especially during frontier campaigns. Medical manuals and surgical instruments have been recovered from forts across the empire, from Germania to Britannia.

Public Health and Sanitation

Roman cities boasted unprecedented public health infrastructure: aqueducts, sewers, latrines, and baths. While not designed with germ theory in mind, these systems reduced disease spread and promoted hygiene.

Physicians occasionally advised city officials on epidemics, water contamination, or diet, although public health policy was not a formalized discipline. Still, Rome’s emphasis on cleanliness and water access set a benchmark for centuries.

Medical Education and Theory

Medical training was often hands-on, beginning with apprenticeship under a practicing physician. Advanced students might study in Greek-speaking medical schools in Alexandria, where dissection and anatomy were explored.

Theories of health centered on the four humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Illness was believed to result from imbalance, treatable through diet, bleeding, or purging. Though flawed, this model encouraged systematic thinking and patient-centered diagnosis.

Women in Roman Medicine

While male doctors dominated the profession, female midwives (obstetrices) played crucial roles in childbirth and gynecological care. Some women became physicians, especially in the Greek East. Their knowledge of herbs, healing rituals, and female anatomy earned them respect in local communities.

Legacy of Roman Medicine

Roman medicine influenced medieval and Renaissance practice profoundly. Galen’s works, based on Roman and Greek observation, became medical canon for over a thousand years. Surgical tools found in Pompeii and Herculaneum are strikingly similar to those used in modern clinics.

Though limited by their era’s knowledge, Roman doctors laid the foundations for clinical observation, medical ethics, and empirical care that endure today.

Instruments of Empire, Tools of Care

In the stillness of a Roman clinic, beneath frescoed walls and flickering lamplight, lives were saved, healed, or simply comforted. With bronze scalpels, herbal salves, and reasoned minds, the medici of Rome practiced a form of healing that straddled science and ritual. Their legacy, carved in steel and scroll, endures in every examination room—and every search for a cure.