Introduction: The Emperor No One Expected

On January 24, 41 AD, chaos reigned in the Roman imperial palace. Emperor Caligula had just been assassinated in a brutal conspiracy led by members of the Praetorian Guard and the Senate. As Rome trembled with uncertainty, a remarkable event unfolded: Claudius, the physically impaired and politically marginalized uncle of Caligula, was discovered hiding behind a curtain. Instead of executing him, the Praetorians saluted him as emperor. Thus began one of the most improbable and consequential reigns in Roman history.

The Julio-Claudian Family and Claudius’ Obscurity

Tiberius Claudius Drusus was born in 10 BC into the prestigious Julio-Claudian dynasty. However, a lifelong limp, speech impediment, and chronic illness led his family to dismiss him as unfit for public life. Sheltered from politics, Claudius turned to scholarship, becoming a historian and linguist. Ironically, this perceived weakness shielded him from the deadly court intrigues that consumed many of his relatives—including his nephew Caligula.

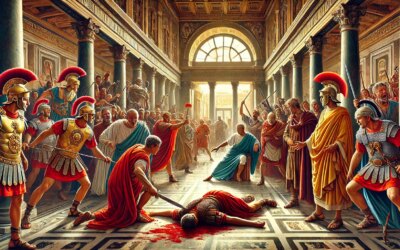

The Assassination of Caligula

Caligula’s short reign had descended into madness, marked by cruelty, extravagance, and humiliation of the Senate. On January 24, 41 AD, a group of conspirators, including Cassius Chaerea, struck him down in a palace corridor. In the ensuing chaos, Rome’s future was uncertain. The Senate considered restoring the Republic, while the Praetorian Guard moved quickly to assert their influence.

The Discovery and Acclamation of Claudius

According to ancient sources, Claudius, fearing for his life, hid in the palace. A Praetorian found him—trembling and disheveled—and rather than kill him, hailed him as emperor. The reasons were pragmatic: Claudius had Julio-Claudian blood and, most importantly, posed no threat to the Guard’s power. Within hours, the Praetorians brought him to their camp and proclaimed him emperor. The Senate, caught off guard and powerless to resist, ratified the choice.

The Rise of Military Influence

Claudius’ acclamation by the army rather than the Senate marked a pivotal shift in imperial politics. It set a precedent for military involvement in succession and diminished the Senate’s influence. The Praetorian Guard received a substantial donative—money paid for their support—thereby institutionalizing bribery as part of future accessions. The office of emperor had become a prize to be claimed and defended by force.

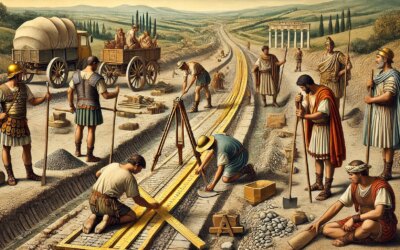

Claudius as Emperor

Despite his unlikely rise, Claudius proved to be a capable and reformist ruler. He expanded the empire by conquering Britain, reformed the judicial system, improved infrastructure, and restored administrative efficiency. He was also known for his interest in law and his unusual accessibility to the public. Claudius ruled for 13 years before being poisoned in 54 AD, allegedly by his wife Agrippina the Younger, to secure the throne for her son Nero.

Historical Perspectives

Ancient historians, often hostile to Claudius due to senatorial bias, portrayed him as bumbling and dominated by freedmen and wives. Modern historians, however, recognize a more complex and competent ruler. Claudius’ policies strengthened imperial authority and stabilized Rome after the turbulence of Caligula’s rule. His reign challenges assumptions about disability, governance, and political adaptability in antiquity.

Conclusion: From Shadow to Scepter

The story of Claudius’ rise in 41 AD is one of paradox and transformation. A man dismissed as a fool by his own family was chosen by force of circumstance and political necessity—and proved to be a wise, if unconventional, ruler. His elevation by the Praetorian Guard marked a new chapter in Roman power dynamics and imperial history. Behind a curtain in the imperial palace, history shifted—and Rome gained an emperor who was never meant to rule, but who changed the empire all the same.