Introduction: A Republic in Peril

In the winter of 63 BC, Rome’s political elite gathered in the Curia Hostilia to confront a threat from within: a coup orchestrated by the disaffected patrician Lucius Sergius Catilina, known as Catiline. As consul, Marcus Tullius Cicero wielded the power of the state’s highest office—and his silver tongue—to expose the conspiracy. His First Oration against Catiline was a dramatic masterstroke of rhetoric, casting a warning that would resonate through Roman history.

Catiline: The Ambitious Conspirator

Born into the noble but financially ruined gens Sergia, Catiline aspired to high office but was thwarted by debts and scandal. Resentful of the Republic’s established order, he recruited a coalition of indebted aristocrats, disillusioned veterans, and urban poor with promises of debt relief and radical reform. By late 63 BC, intelligence reports revealed plans to assassinate leading senators, burn the city, and seize power.

Cicero: The Novus Homo Consul

Cicero, a “new man” (novus homo) without noble lineage, had risen to the consulship through legal advocacy and political acumen. Alarmed by the conspiracy, he convened the Senate on November 8, 63 BC. In a rapid turnaround, Cicero prepared a speech that would not only unmask Catiline’s plot but also assert the primacy of lawful governance over subversion.

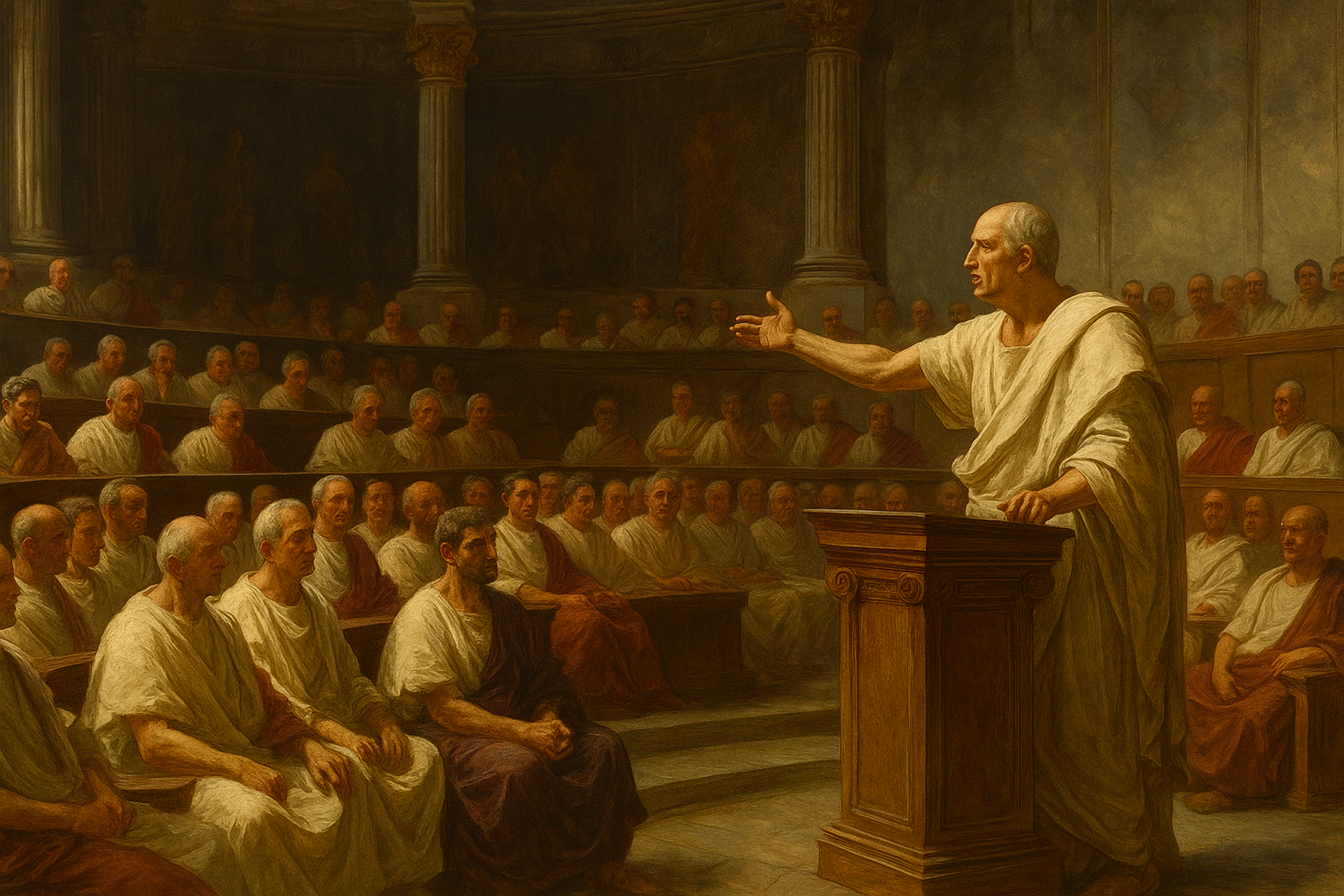

The First Oration Delivered

Standing at the speaker’s platform, Cicero began with the famed words, “Quo usque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra?” (“How long, O Catiline, will you abuse our patience?”). He recounted evidence of the conspiracy: secret gatherings, stolen funds, and plans to set fire across Rome. Cicero’s rhetoric combined fact with moral invective, painting Catiline as a traitor to the res publica and a threat to every citizen’s safety.

Senatorial Reaction and Aftermath

The Senate, shocked and galvanized, issued the senatus consultum ultimum—the ultimate decree—granting Cicero extraordinary powers to protect the Republic. Catiline, present in the chamber, delivered a defiant retort before fleeing Rome to join his forces in Etruria. Cicero followed with two more speeches, securing the arrest of conspirators in the city. Catiline’s eventual defeat and death in battle ended the immediate danger.

Constitutionality and Controversy

Cicero’s actions, though celebrated, sparked debate. Critics argued that his summary executions of conspirators without trial violated Roman law. His defenders cited the emergency powers of the senatus consultum ultimum. The controversy haunted Cicero’s career—years later, the triumvirs would exile him, partially blaming his decisions of 63 BC.

Legacy of the Oration

The “Catiline Orations” became cornerstones of rhetorical education, showcasing Cicero’s mastery of style, structure, and ethos. His plea to the Senate remains a defining moment in the assertion of republican ideals against authoritarian plots. The speeches preserved in Livy, Sallust, and Cicero’s own writings illustrate the tension between liberty and security—a theme echoing through political thought ever since.

Conclusion: Speech as a Weapon of the Republic

In exposing the Catiline conspiracy, Cicero demonstrated that oratory could be as potent as armies in defending the state. The First Oration against Catiline fused persuasive brilliance with legal authority, reaffirming the Roman commitment to the rule of law. Though Catiline’s defeat did not cure all of Rome’s ills, it solidified Cicero’s reputation as the voice of the Republic—and a testament to the power of words in the corridors of power.