The Silent Scholars of Rome: A Different Kind of Education

In the grand villas of patricians and the modest homes of merchants, education in ancient Rome shaped more than minds—it defined identities and futures. While the education of boys in rhetoric, philosophy, and law has been extensively chronicled, the education of girls remains a quieter, more nuanced chapter. Yet young Roman girls—particularly from elite families—did receive education, primarily at home, laying the groundwork for their expected roles as cultured, virtuous matrons. Their learning, though constrained by societal boundaries, reveals Rome’s deep connection between literacy, morality, and public virtue.

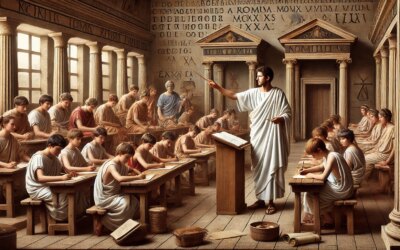

Learning at Home: Tutors and Family Instruction

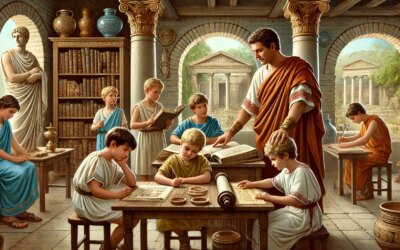

Unlike boys, who might attend formal schools or study under philosophers, girls were typically educated at home. Instruction often began as early as age six or seven, usually provided by private tutors known as paedagogi or by parents themselves. Mothers played a crucial role—particularly those with cultural ambitions or literary backgrounds. Well-documented figures like Cornelia Africana, mother of the Gracchi, became renowned for instilling moral and intellectual rigor in their children.

The curriculum included:

- Basic literacy: reading and writing Latin (and sometimes Greek) using wax tablets and styluses.

- Arithmetic: useful for managing household accounts and estate affairs.

- Domestic management: training in textile work, food preparation, and hosting etiquette.

- Moral instruction: learning traditional Roman values through texts like the Annales Maximi or family genealogies.

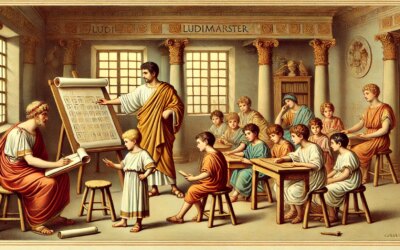

Instruments of Learning: Tablets and Tradition

Girls learned with the same tools as boys—wax tablets (tabulae ceratae), wooden styluses, scrolls of Virgil or Ennius—but with different aims. While a boy might train to argue in court, a girl learned to recite poetry or draft letters for family correspondence. Still, the tools fostered intellectual curiosity. In wealthier households, girls might also be exposed to Greek, music, or even philosophical dialogue, especially if their family moved in cosmopolitan circles.

Famous Learned Women: Outliers or Icons?

While rare, a number of educated Roman women are known to history. Sulpicia, a 1st-century BC poet, wrote elegant love elegies in the style of Tibullus, challenging assumptions of women’s illiteracy. Julia Balbilla, a noblewoman and companion of Emperor Hadrian, inscribed Greek epigrams on the Colossi of Memnon during a Nile visit. Hypatia of Alexandria, though later and in the Greek East, remains the most famous female philosopher of antiquity—her story showing both the heights and the dangers faced by educated women.

Girls of the Plebs: A Different Classroom

For lower-class girls, education was far more practical. While literacy was less common, many learned skills by apprenticeship—working in shops, markets, or alongside mothers in homes. Inscriptions reveal female bakers, midwives, scribes, and even businesswomen who had acquired enough literacy to sign contracts or manage trade. In urban centers like Ostia and Pompeii, graffiti and shop signs attest to women’s everyday interactions with written language.

The Limits of Roman Pedagogy

Despite these achievements, education for girls remained framed by patriarchal limits. Girls were seldom prepared for public office or philosophical debate. Their learning was meant to enhance their role within the domus (household) and to project a family’s honor. Elite marriages, often arranged by age 14, curtailed educational trajectories. Yet even within these bounds, educated women could exert influence through writing, social networks, and childrearing.

Legacy and Influence

Roman ideals of female education—focused on virtue, eloquence, and domesticity—would deeply influence medieval and Renaissance attitudes. Christian mothers like Monica, mother of Augustine, carried forward the Roman matron model. In art and literature, the learned Roman matron appeared as a symbol of refined motherhood and civic grace.

Voices Preserved in Wax and Stone

While few writings from Roman girls survive, their educational world can be glimpsed in mosaics, inscriptions, and recovered tablets from sites like Vindolanda. These artifacts tell a subtle but powerful story: that Roman girls, though often silent in history, shaped the values and culture of their world from the atrium outward. With stylus in hand and mother beside her, a girl might not have written orations—but she wrote a legacy nonetheless.