Rome’s Forgotten Artery Beneath the Streets

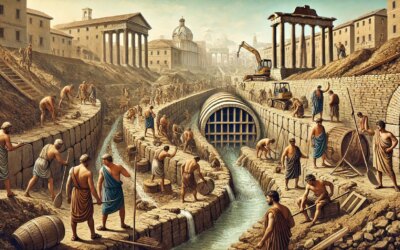

Long before aqueducts carried fresh water to marble fountains or the Colosseum echoed with roaring crowds, the early Romans tackled a less glamorous but equally vital challenge: sanitation. At the heart of this effort was the Cloaca Maxima, one of the world’s earliest and most ambitious sewer systems, built in the 6th century BC under the reign of King Tarquinius Priscus.

Though it lies buried beneath the streets of modern Rome, the Cloaca Maxima was a transformative engineering feat that not only helped to drain the swamps between the Palatine and Capitoline Hills but also enabled the city to grow into a metropolis of over a million people centuries later. It remains, even today, a symbol of Rome’s early genius in civil engineering.

The Origins of the Sewer System

The site of early Rome was marshy and vulnerable to flooding from the Tiber River. The valleys between the hills were essentially wetlands, unsuitable for construction or habitation. According to Roman tradition, King Tarquinius Priscus (r. ca. 616–579 BC), the city’s fifth king, undertook a bold project: to drain these lowlands by constructing a massive underground canal system to redirect wastewater and storm runoff into the Tiber.

Using primitive tools, Roman engineers and forced laborers (likely both slaves and local workers) excavated vast trenches, lining them with stone and creating vaulted tunnels. What began as an open-air canal was eventually roofed over and expanded as the city grew. By the 2nd century BC, it was a fully enclosed sewer stretching beneath the heart of the Forum Romanum.

Design and Engineering Brilliance

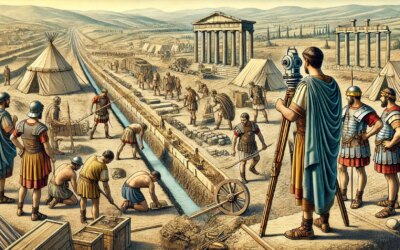

Though ancient, the Cloaca Maxima demonstrates a remarkable understanding of hydrodynamics and load-bearing architecture. It employed corbelled vaults and later true arches—long before such methods became widespread in the Mediterranean. The main channel was large enough to walk through, and smaller branch tunnels fed into it from private homes, public baths, and latrines.

Its durability is astounding. The original tunnel, carved from volcanic tufa and lined with ashlar blocks, survived floods, earthquakes, and even the occasional Imperial renovation. Roman engineers relied heavily on gravity, ensuring that the slope of the channels carried waste efficiently without modern pumps or mechanical aid.

The Urban Impact

The Cloaca Maxima wasn’t just about removing waste—it was foundational to Rome’s urban identity. With proper drainage, the valleys between the hills could support markets, temples, and public buildings. The Forum, arguably the most sacred civic space in Roman life, owes its very existence to the Cloaca’s ability to make the area habitable.

Moreover, the system set a precedent. Future Roman cities, from Londinium to Antioch, would emulate this model. Sewage systems became a defining feature of Roman urban planning, helping reduce disease, manage floods, and maintain hygiene in increasingly dense urban centers.

Maintenance and Expansion

Maintaining the Cloaca was no small feat. Regular inspections and clearings were necessary to prevent blockages. The job fell to various public officials, including the aediles, who were responsible for urban upkeep. In Imperial times, emperors such as Augustus and Claudius oversaw renovations, and graffiti from maintenance workers can still be found in its stone tunnels.

The system also evolved over time. During the Republican and early Imperial periods, additional tunnels were dug to serve new neighborhoods, baths, and latrines. Innovations such as lead piping and settling basins improved its functionality, making it one of the most advanced sanitary systems in the ancient world.

The Sacred and the Profane

Interestingly, the Cloaca Maxima also held religious significance. Because it emptied into the Tiber—a sacred river to the Romans—it was seen not just as a utility but as part of the city’s divine connection to nature. The goddess Cloacina, originally an Etruscan water deity, was associated with the sewer system and had a small shrine near the Forum.

Thus, the Cloaca Maxima straddled a curious line between engineering and theology—both a marvel of practicality and a symbol of the Roman worldview, where even sanitation was imbued with ritual significance.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

Portions of the Cloaca Maxima are still accessible today, and parts of it still function in the modern drainage of Rome. Though its original scale has been diminished by centuries of overbuilding and modern plumbing, it remains a testament to Rome’s enduring engineering legacy.

Modern cities around the globe owe a debt to the principles embedded in this ancient system. Concepts like gravity-fed drainage, public sanitation infrastructure, and urban hydrology have roots in the Cloaca Maxima’s design. It is a striking reminder that even the most overlooked elements of civilization—waste management, infrastructure, drainage—are vital to sustaining life and culture.

More Than a Sewer

In the story of Rome’s greatness, the Cloaca Maxima rarely earns the spotlight. Yet without it, the grandeur of temples, the bustle of markets, and the pageantry of triumphs would have been impossible. Beneath the marble and myth of ancient Rome runs a river of ingenuity—one that began with a simple, monumental act of draining the land to raise a civilization.