Marketplace of an Empire

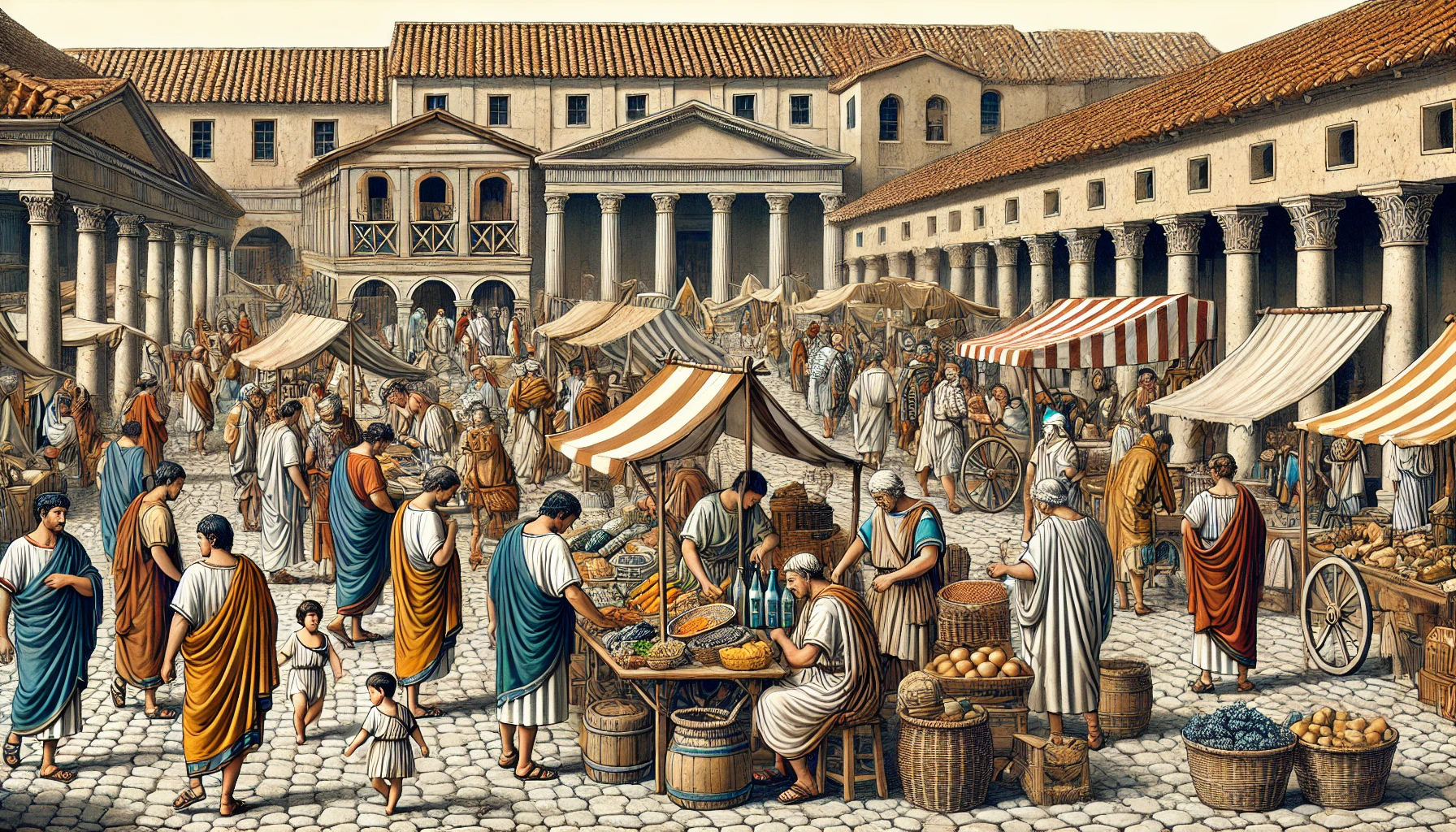

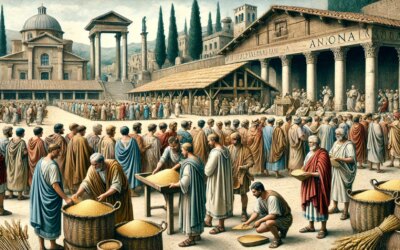

In the quiet morning hours of a Roman provincial town in the 2nd century AD, the forum begins to stir. Merchants unwrap their wares, citizens gather to exchange gossip, and the smell of bread and spices fills the air. The Roman market—forum venalium—was more than a place to shop. It was an economic lifeline, a social hub, and a mirror of Rome’s imperial reach.

The Layout and Life of the Market

Provincial Roman markets were modeled on their metropolitan counterparts in Rome. Located near the forum or civic center, they were framed by colonnades, stone stalls, fountains, and statues of emperors or local magistrates. Covered markets (macella) offered shade and shelter, while open plazas hosted vendors under canopies or umbrellas.

Key features included:

- Designated stalls for butchers, bakers, fishmongers, and grocers.

- Central fountains for washing produce and hands.

- Temples or altars nearby for offerings before trade.

- Inscribed tariffs and price lists posted by local aediles to prevent fraud.

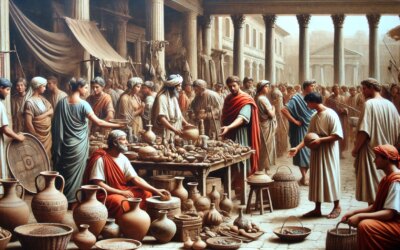

What Was for Sale?

The 2nd century AD marked the height of Rome’s territorial expanse, and the markets reflected that diversity. On a typical day, shoppers might find:

- Grain and bread from local harvests and imperial shipments.

- Fruits and vegetables grown in surrounding farms—figs, grapes, olives, onions.

- Meat and fish sold fresh, dried, or salted, depending on proximity to coasts or rivers.

- Imported goods like Egyptian spices, Gallic wines, Syrian textiles, or Spanish oil.

- Craft goods—pottery, glassware, metal tools, sandals, and jewelry.

Prices fluctuated with supply, season, and transportation. Haggling was common, and repeat customers developed close relationships with their preferred vendors.

The People of the Market

Markets were melting pots. Citizens, freedmen, slaves, soldiers, and foreigners mingled freely. Merchants ranged from local producers to long-distance traders who traveled with their goods. Many vendors were freedmen—former slaves who used their skills and savings to run small businesses.

Children played while their parents shopped. Women came to buy for their households, sometimes accompanied by slaves or servants. Soldiers patrolled or visited stalls on leave, adding both discipline and liveliness to the scene.

The aediles—municipal officials—oversaw weights, measures, hygiene, and pricing. Fraudulent merchants faced fines or public shaming.

Trade Networks and Infrastructure

Even small provincial towns were connected to the vast Roman trade network. Roads, bridges, and ports enabled goods to flow swiftly between regions. An amphora of oil from Hispania, a bolt of cloth from Asia Minor, or a jar of garum (fish sauce) from Baetica might find its way into the baskets of provincial buyers.

This infrastructure was maintained by Roman engineers and funded through imperial taxation and local tribute. Markets were not just commercial—they were manifestations of Roman order and integration.

Festivals, Politics, and the Forum

Markets often coincided with religious festivals, political events, or court proceedings. The civic forum—adjacent to the commercial area—hosted speeches, trials, and announcements. On festival days, musicians performed, actors entertained, and temples offered sacrifices. These days saw increased foot traffic and sales.

Local elites used the market to curry favor—sponsoring events, donating fountains, or funding grain handouts. Inscriptions record their generosity, often tied to election campaigns or imperial honors.

Prices and Currency

Most transactions were in coin—denarii, sestertii, asses—though bartering occurred, especially in rural zones. Coinage ensured standardization across the empire, and currency exchange was available for foreign traders.

Prices were regulated, especially for essentials like bread and oil. The imperial government occasionally issued price edicts, as seen later in the Edict on Maximum Prices under Diocletian (301 AD), though localized controls existed earlier.

Echoes in Stone and Soil

Excavated Roman markets, like those in Pompeii, Ostia, and Leptis Magna, reveal mosaic floors, weighing stations, shop counters, and graffiti advertising goods. Inscriptions preserve names of merchants, patrons, and regulations. These sites give us a vivid picture of commerce and community at the empire’s grassroots.

The Market as Mirror

Roman provincial markets reveal much more than trade. They show how culture, economy, governance, and daily life intertwined. Here, Latin mixed with local dialects, olive oil fueled both lamps and meals, and Roman values mingled with regional customs.

For modern historians and visitors alike, the Roman market offers a window into the rhythms of ancient life—practical, vibrant, and profoundly human.