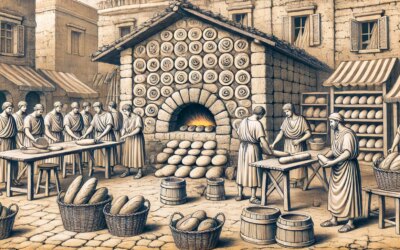

Morning Ritual at the Fornax: Opening the Bakery

In the heart of the Suburra district, where winding alleys echo with the chatter of merchants and citizens, the day for a Roman baker began before dawn. By 4 AM, the pistor (baker) and his assistants—often freedmen or slaves—kindled fires in the clay and brick oven known as the fornax. Maintaining precise heat was an art: too intense, and the crust would char; too low, and loaves remained doughy. Seasoned pistriones gauged temperature by tossing a pinch of flour; if it browned in seconds, the oven was just right.

Mixing the Masa: Ingredients and Preparation

Roman bread, unlike modern loaves, varied widely. The staple panis plebeius, a coarse whole-grain variant, fed the masses, while the elite indulged in refined panis cervisius or panis triticalis made with imported wheat. Bakers sourced grain from rural suppliers and public granaries. Each batch of dough combined 30% grain with water, salt, and—occasionally—olive oil or honey for flavor. After mixing in large wooden troughs, the dough rested for levatio, rising on mats woven of reeds.

Shaping and Scoring: The Baker’s Signature

Once risen, the dough was portioned into various shapes: round placenta loaves, cylindrical buccellatum, and flat lagana resembling modern focaccia. Scoring the surface—often with a stylus or knife—helped steam escape and created signature patterns, marking each baker’s work in crowded bakeries. Inscriptions scratched on the crust sometimes indicated weight or grade, ensuring accurate sales at the macellum (food market).

Baking and Beyond: From Oven to Table

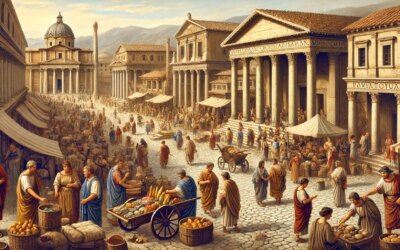

During the peak hours of dawn to mid-morning, the pistor’s team managed a continuous cycle: loading unbaked loaves with long-handled paddles (ligo), monitoring bake times, and unloading golden-brown bread. Baskets lined with cloth held fresh loaves awaiting delivery. Wealthy patrons sent actuarii (messengers) to collect bespoke orders, while the populace queued at the shopfront or within the horrea (grain storage warehouses) for subsidized annona distributions.

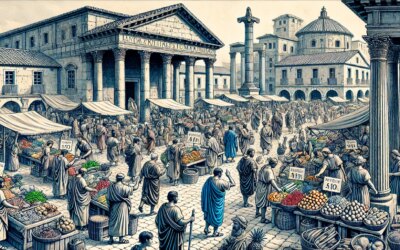

Economic and Social Role of Bakeries

Bakery workshops served as hubs of community life. Patrons exchanged news as they waited, and artisanal guilds—collegia pistorum—regulated quality and training. Imperial rules mandated standard loaf sizes and weight tolerances to prevent fraud, enforced by the aediles. During grain shortages, magistrates auctioned public grain at fixed prices, and bakers played a vital role in preventing civil unrest.

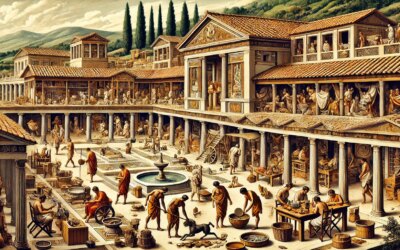

Challenges and Innovations

Urban fires posed constant threats. In 6 AD, Emperor Augustus established stricter fire codes for bakeries, requiring wider alleyways and soot-free chimneys. Technological adaptations included the introduction of water-powered mills—molendina—reducing reliance on animal labor and improving flour consistency. Late Republic bakers experimented with sourdough starters (pultis fermentata), enhancing flavor and bread shelf life, as documented by Cato the Elder in De Agri Cultura.

Evening Aftermath: Cleaning and Preparation

As afternoon waned, the pistor cleaned the bakery: ashes removed from the oven floor, tools washed, and residual dough scraps fed to pigs. By sunset, a small batch of panis militaris—hardened biscuits for legionaries—would be prepared and dried in the residual heat, ensuring Rome’s soldiers received durable rations before campaigns.

The Legacy of Roman Baking

Roman bread set foundations for European baking traditions. The communal ovens in medieval towns mirrored ancient fornaces, and sourdough techniques persisted through the Middle Ages. Today’s archaeological excavations in Pompeii reveal clay bread molds bearing bakers’ stamps, linking modern loaves to their ancient ancestors. The simple act of breaking bread thus remains a timeless testament to Rome’s culinary and social ingenuity.