A Window into Roman Civilization

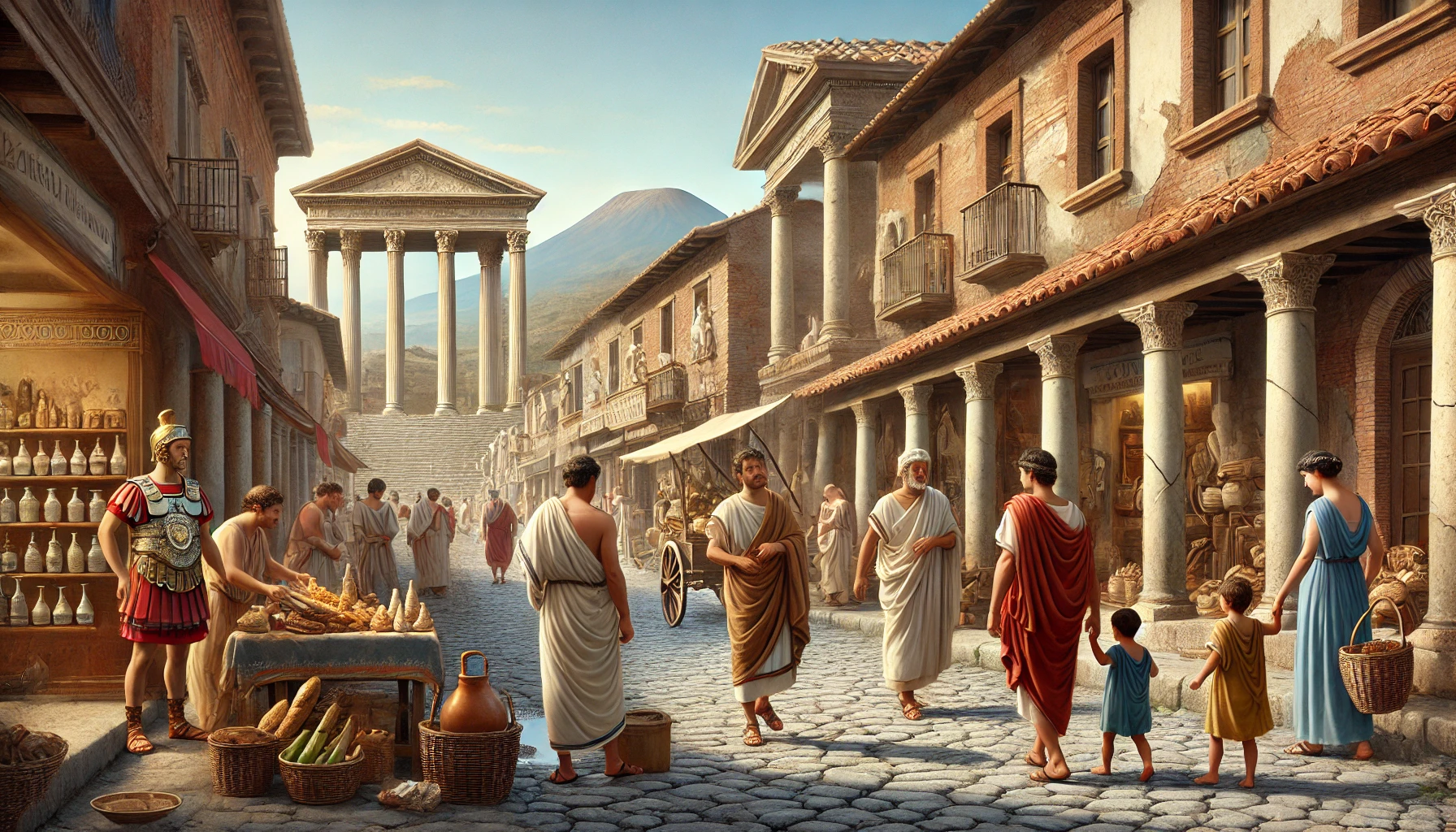

In the bustling Roman town of Pompeii, nestled near the Bay of Naples, daily life unfolded with vibrancy and routine under the reign of Emperor Claudius (41–54 AD). Long before its tragic destruction in 79 AD, Pompeii offered a vivid snapshot of Roman urban life. Thanks to the preservation of its ruins beneath volcanic ash, we know more about this city than nearly any other in antiquity. But what was life truly like in Pompeii around 50 AD?

The Rhythm of a Roman Morning

The streets of Pompeii would begin stirring at dawn. Citizens clad in tunics and togas moved along the stone-paved viae, some heading to temples, others to markets or public baths. Shopkeepers opened their tabernae—street-facing commercial spaces attached to houses—selling fresh bread, olives, wine, and dried fruits. Public fountains gushed from lead aqueduct-fed pipes, and children played with wooden toys or tossed nuts like dice.

The typical Roman home, or domus, opened with an atrium, where a family’s identity was on display. Mosaic floors bore geometric patterns or mythological scenes, while lararia (household shrines) honored protective spirits. Some homes doubled as workplaces, where artisans crafted jewelry, leather goods, or cloth for sale.

Vibrant Commerce and Crafts

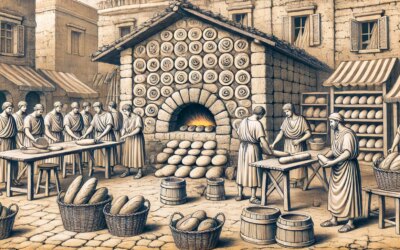

Pompeii thrived on commerce. Bakers kneaded loaves in domed ovens, marked with stamps identifying the baker. Garum factories processed fermented fish sauce, a prized Roman condiment exported across the empire. Fullers washed and bleached clothing in vats of urine and water. Cobblers, potters, and blacksmiths plied their trades—evidence of which remains in the preserved tools and graffiti of Pompeian workshops.

Markets were organized by function: produce, meat, fish, and imported luxuries. Local farmers and distant merchants alike found customers among the 11,000–15,000 residents. Currency ranged from bronze asses to silver denarii, and barter still played a role.

Religion and Ritual in the Streets

Pompeians were devout. Small temples to Venus, Apollo, and Jupiter dotted the city, while household shrines and public altars anchored everyday worship. The cult of Isis had gained a following, especially among women and freedmen. Religious festivals punctuated the calendar—some official, others more localized, like the celebration of local spirits or ancestral rites. Street musicians, mimes, and dancers added spectacle to sacred days, blurring lines between faith and entertainment.

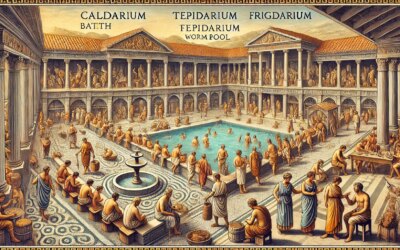

Public Baths and the Social Hub

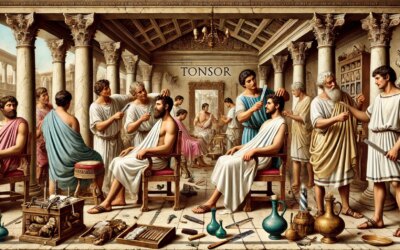

No day in Pompeii was complete without a visit to the baths. Complexes like the Stabian and Forum Baths offered heated pools, steam rooms, cold plunges, and massage oils. More than hygiene, baths were centers of social life. Men and women bathed in separate hours or quarters, discussing politics, business, or gossip.

Exercise courtyards, libraries, and shaded gardens accompanied the baths, making them the equivalent of civic centers. Entry was cheap—subsidized by local elites vying for popularity—and attendance spanned all classes, from slaves to senators.

Entertainment on Every Corner

Theaters, gladiator barracks, and taverns (or popinae) kept Pompeians entertained. The Large Theater hosted plays in Latin or Oscan, while the amphitheater, built around 80 BC, seated 20,000 for gladiatorial combat and beast hunts. Wall inscriptions announced upcoming spectacles: “On the 15th, games! Wild animals and net fighters!”

Taverns offered wine, hot meals, and occasionally upstairs rooms for rent. Gambling, debates, and flirtation filled these spaces, which were as common as modern cafés.

Voices from the Walls

Graffiti immortalized the candid thoughts of everyday Romans. In scrawled Latin, citizens praised lovers, mocked rivals, endorsed political candidates, or simply proclaimed, “Marcus was here.” In one brothel, a drawing advertised services; in a villa atrium, a poetic line mourned a lost pet. These words bring Pompeii to life not as a museum, but a lived-in city, full of humor, desire, and humanity.

Looking Back from the Shadow of Vesuvius

Though Pompeii is best known for its tragic end in 79 AD, its earlier life under Claudius reveals the cultural richness of a Roman provincial town at its height. Its citizens lived in color, worshiped passionately, worked skillfully, and played with gusto. Their preserved city is more than ruin—it is a testament to what made Roman life ordinary and extraordinary.