Introduction: A Republic in Turmoil

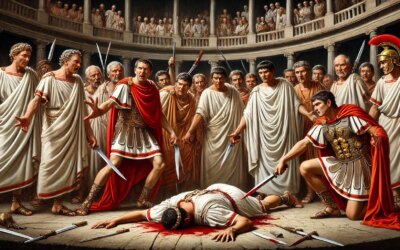

The assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BC—known forever as the Ides of March—sent a seismic shock through the heart of the Roman Republic. As senators stood over the blood-stained floor of the Theatre of Pompey, Caesar’s lifeless body symbolized not only the fall of a man but the unraveling of an era. The Senate, divided and anxious, now faced an uncertain future. Would the Republic be restored—or torn apart?

The Scene in the Senate

In the days following the assassination, the Senate reconvened under the shadow of fear and confusion. Many senators, even some conspirators, feared retaliation from the people or Caesar’s loyalists. The Senate House, draped in mourning, bore witness to urgent and volatile debate. The empty curule chair of Caesar, covered in the imperial purple cloak he had worn, became a powerful image of sudden vacancy and contested legitimacy.

Caesar’s Legacy and the Power Vacuum

Though dead, Caesar’s influence lingered. As dictator perpetuo, he had centralized power in a way unseen since the days of the early kings. His reforms—land distributions, calendar changes, military reassignments—were incomplete. His will, revealed days after his death, named his great-nephew Octavian as heir and generously distributed money to the Roman populace. The people’s grief turned to fury, and public support for Caesar surged.

The Conspirators: From Liberators to Fugitives

Led by Brutus and Cassius, the assassins called themselves “liberators,” claiming they had saved the Republic from tyranny. But the reaction from the Roman masses was not as they had hoped. Instead of acclaim, they were met with condemnation and fear. Forced to flee Rome, they watched from afar as their dream of restoring the Republic slipped away.

Mark Antony’s Maneuvering

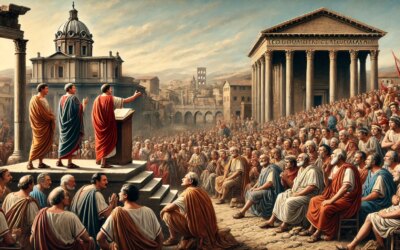

As Caesar’s close ally and consul, Mark Antony seized the political moment. He orchestrated a dramatic public funeral, displaying Caesar’s bloodied toga and rousing the crowd with a fiery oration. The Senate’s effort to balance peace and justice—granting amnesty to the conspirators while upholding Caesar’s acts—was rapidly crumbling under the weight of public emotion and Antony’s ambition.

The Rise of Octavian

Into this chaos stepped Octavian, a teenager with a famous name and formidable ambition. Despite his youth, he skillfully rallied Caesar’s veterans and positioned himself as the true heir—not just to Caesar’s estate, but to his vision. Over the next months, the alliance between Antony and Octavian would falter, evolve, and ultimately fracture the Republic into new civil wars.

The Senate’s Waning Authority

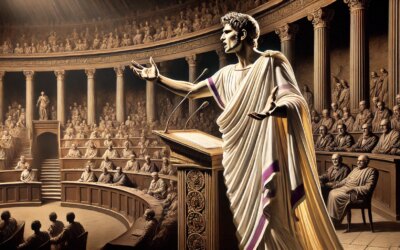

The events of 44 BC revealed the Senate’s declining power. Once the fulcrum of Roman politics, it had become a reactive body, struggling to contain the ambitions of generals and populists. Its symbolic mourning after Caesar’s death could not mask its growing irrelevance. The Republic, nominally intact, now functioned at the whim of rival warlords.

Conclusion: Mourning the Man, Foretelling the Empire

The mourning of the Senate after Caesar’s assassination was more than a moment of grief—it was a prelude to transformation. The Republic, long strained by inequality, war, and populism, stood at the edge of collapse. Within two decades, Augustus—formerly Octavian—would stand as Rome’s first emperor. What the senators had hoped would preserve the Republic instead catalyzed its demise. In the silence around Caesar’s empty chair, Rome’s future was already being written.