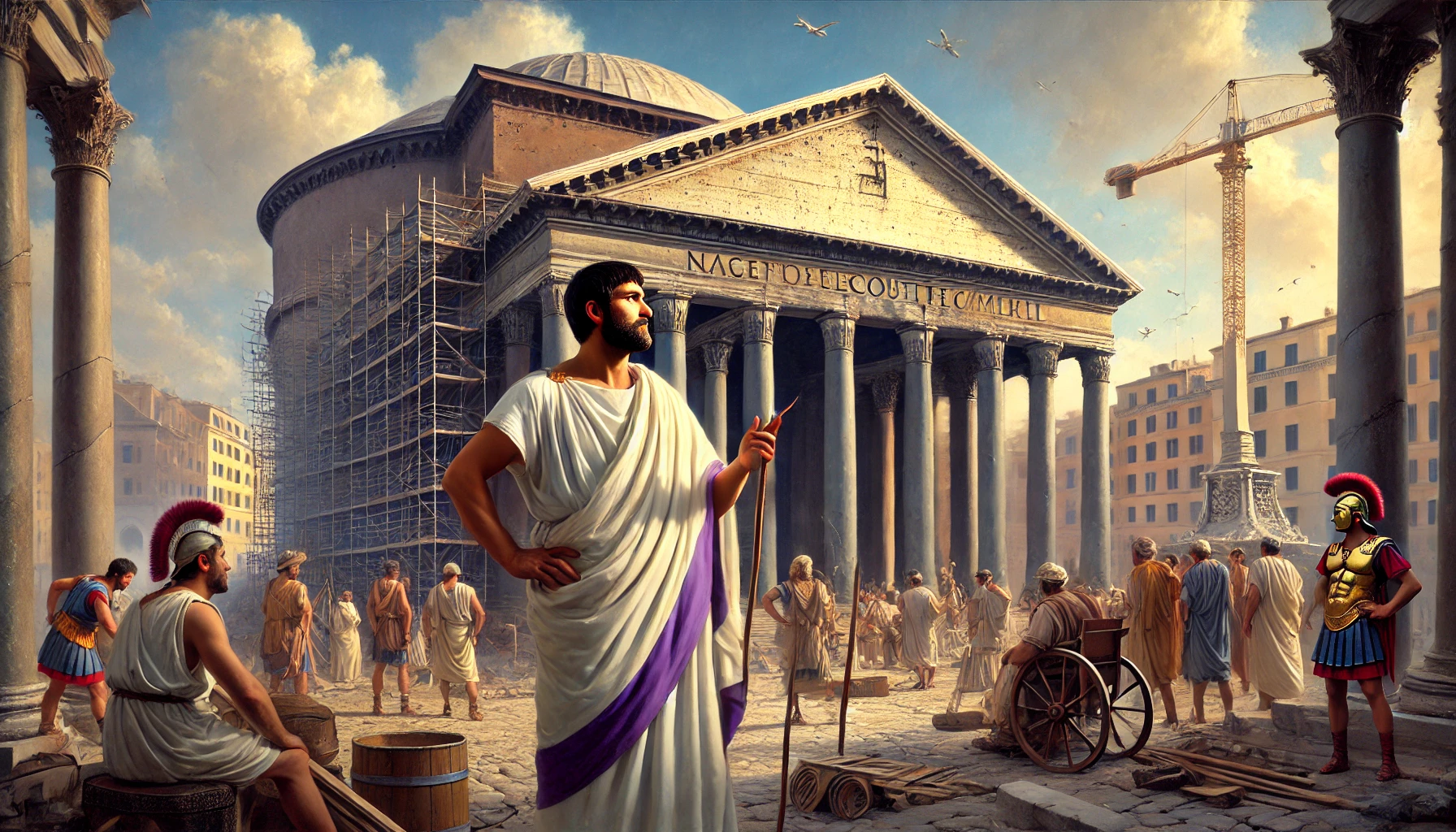

Introduction: Building for the Gods and the Empire

In the transformative year of 27 BC, as Rome transitioned from Republic to Empire under Augustus, a grand architectural vision began to rise on the Campus Martius: the Pantheon. Though the current structure visible today dates from Hadrian’s era, the original concept belonged to Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa—Augustus’s most trusted general, strategist, and builder. His first Pantheon laid the foundation not only for one of the world’s greatest temples but for a new architectural language of Roman power.

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa: More Than a General

Born around 63 BC, Agrippa was a childhood friend and lifelong ally of Octavian, later Augustus. He played a decisive role in the civil wars, defeating Sextus Pompey at Naulochus and Mark Antony at Actium. Yet beyond the battlefield, Agrippa was a visionary administrator and patron of infrastructure. As aedile, he overhauled Rome’s water supply, cleaned its streets, and commissioned numerous public works—including the Pantheon.

The Context of 27 BC

Augustus had just been granted extraordinary powers by the Senate, initiating the Principate. Rome needed symbols of this new stability and divine sanction. Agrippa, acting in alignment with Augustus’s vision, began constructing a temple that honored all gods—hence the name “Pantheon.” Located in the heart of civic life, it would become a focal point of political theology and architectural innovation.

The Design of Agrippa’s Pantheon

The original Pantheon, completed around 25 BC, was quite different from the iconic domed building we know today. It featured a traditional rectangular temple front with Corinthian columns and a deep portico, possibly facing south. Behind it stood a circular courtyard or rotunda, the details of which remain speculative due to later reconstructions. What set it apart was its purpose: a temple not to one god, but all—reflecting the unity Augustus sought to impose on Rome’s diverse religious landscape.

Engineering and Innovation

Agrippa’s engineers pioneered construction methods that blended Greek design with Roman scale. Marble, travertine, and volcanic tufa were utilized strategically. The Pantheon stood as a showcase of Roman engineering ambition—both technically and ideologically. In its proportions and materials, it echoed the Augustan message: the empire was grounded in tradition, but reaching toward eternity.

Dedication and Inscription

The inscription Agrippa left on the building—“M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT” (“Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, made [this building] when consul for the third time”)—survives today on the Hadrianic reconstruction. It reflects both humility and pride: Agrippa dedicated the building in his own name, not Augustus’s, a rare gesture that hints at their close trust and shared vision.

The Fire and Rebuilding

The Pantheon suffered two major fires, in 80 AD and again around 110 AD. Each time it was rebuilt, culminating in Hadrian’s monumental version completed around 126 AD. Yet Agrippa’s original concept endured. Even Hadrian kept the original inscription, a nod to the structure’s founding spirit and its enduring symbolism of imperial unity and divine order.

Legacy of Agrippa’s Vision

Agrippa’s Pantheon was not merely a temple—it was an embodiment of Augustan ideology. It expressed the Pax Romana, the harmony of gods and empire, and the architectural confidence of a city at the center of the world. Though his version no longer stands, his vision echoes through the columns and dome of its successor, a living monument to one man’s blend of pragmatism, loyalty, and divine imagination.

Conclusion: Foundations That Endured

In 27 BC, Marcus Agrippa began more than a building—he initiated an architectural conversation that would stretch across millennia. His Pantheon, born in a time of political renewal and imperial consolidation, remains a cornerstone of Roman legacy. As the stones rose, so too did the ideals of an empire—disciplined, enduring, and ever reaching toward the heavens.