The Eastern Queen Who Challenged Rome

In the mid-3rd century AD, as the Roman Empire struggled against internal instability and external invasions, one city rose in unexpected defiance—Palmyra. Under the leadership of Queen Zenobia, this wealthy and cosmopolitan desert city transformed into an imperial power, claiming control over much of the eastern Roman provinces. But in 273 AD, Emperor Aurelian launched a swift and decisive military campaign to bring Palmyra back under Roman rule. The fall of Palmyra marked a critical moment in the restoration of the empire, showcasing both the ambitions of Rome’s enemies and the relentless resolve of its generals.

The Rise of Palmyra and the Ambition of Zenobia

Palmyra had long been a semi-autonomous city within the Roman sphere, flourishing as a trading hub between East and West. Following the death of her husband, Septimius Odaenathus, in 267 AD, Zenobia assumed regency over their young son and quickly asserted real control. Over the next few years, she expanded Palmyrene authority across Syria, Egypt, and parts of Asia Minor—territories still technically under Roman control.

Zenobia declared independence in all but name. In 271 AD, she openly broke with Rome, proclaiming her son emperor and issuing coinage in his name. The Palmyrene Empire had arrived, and Zenobia—intelligent, charismatic, and politically astute—became its sovereign face. Her rebellion came at a time when the Roman Empire was deeply fractured, with multiple usurpers and the Gallic Empire still seceded in the west.

Aurelian’s Campaign to Reclaim the East

Emperor Aurelian, who rose to power in 270 AD, was determined to reunify the empire. A former cavalry commander with a reputation for discipline and military brilliance, Aurelian swiftly secured the Danube frontier before turning his gaze eastward. By 272 AD, he launched his campaign against Zenobia, advancing through Anatolia and reclaiming province after province with minimal resistance.

Aurelian’s strategy combined military force with careful diplomacy. Many cities welcomed Roman authority, unwilling to risk destruction for Zenobia’s cause. Still, Palmyra itself remained defiant. Zenobia prepared for a siege, drawing strength from the city’s fortified walls and strategic desert position.

The Siege and Capture of Palmyra

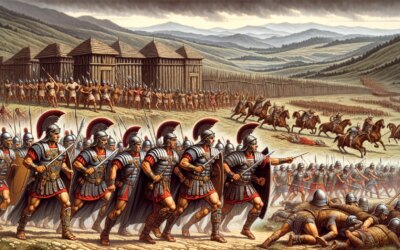

In the autumn of 272 AD, Aurelian reached Palmyra and laid siege. His forces, composed of veteran legions and cavalry, surrounded the city. The Palmyrene defenders, including archers and cavalry drawn from desert tribes, fought tenaciously. But they lacked the manpower and cohesion of the Roman army.

Facing dwindling supplies and no reinforcements, Zenobia attempted a daring escape eastward to seek Persian support. She was captured near the Euphrates and brought back to Aurelian in chains. Shortly thereafter, the city surrendered. Aurelian initially spared Palmyra, recognizing its economic and strategic value. Zenobia was taken to Rome, paraded in a triumph, and—according to some sources—granted a quiet retirement.

The Second Revolt and Total Destruction

In 273 AD, Palmyra revolted once more, perhaps under false rumors of Zenobia’s restoration or in response to harsh Roman administrators. This time, Aurelian responded without mercy. His forces returned and destroyed the city. Palmyra’s buildings were burned, its population decimated, and its status as a major power extinguished. The message was clear: no province, however rich or independent, would be allowed to defy Rome twice.

The Legacy of Aurelian’s Victory

The fall of Palmyra marked a turning point in the Crisis of the Third Century. Aurelian’s campaign restored the eastern provinces, demonstrating the effectiveness of centralized Roman authority. Within a year, he would go on to defeat the Gallic Empire in the west, completing his mission to reunify the empire—a feat not accomplished since the reign of Valerian decades earlier.

Aurelian earned the title Restitutor Orbis—“Restorer of the World”—and his military successes laid the groundwork for the later stability under Diocletian. Though he would be assassinated in 275 AD, his reign marked the beginning of Rome’s recovery from near collapse.

Palmyra’s Ghost in the Desert

Today, the ruins of Palmyra still stand in the Syrian desert—a haunting reminder of a city that once defied an empire. Columns and temples, now damaged by time and war, whisper of Zenobia’s grandeur and Aurelian’s fury. The campaign of 273 AD remains a dramatic chapter in Roman military history: the end of a rebellion, the assertion of imperial might, and the final act of a queen who dared to rule in Rome’s shadow.