Feeding the Empire One Loaf at a Time

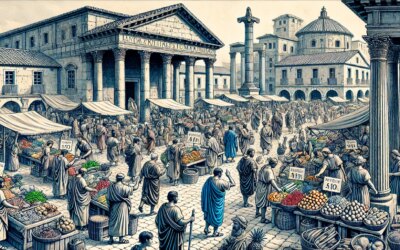

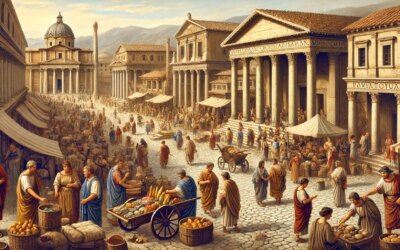

In the labyrinthine streets of ancient Rome, the smell of freshly baked bread was as familiar as the clang of the blacksmith’s forge or the cries of market vendors. In the 1st century AD, bakeries—pistrina—were vital institutions in Roman urban life. They were not merely places of sustenance, but hubs of economic activity, social interaction, and daily ritual. Bread was the staple of the Roman diet, and the bakers who produced it were essential to keeping the city alive.

The Role of Bread in Roman Diet

Grain, especially wheat, formed the core of the Roman diet. From emperors to laborers, bread was a daily necessity. The varieties were numerous—panis quadratus (round loaves marked with dividing lines), panis siligineus (white bread), panis militaris (for soldiers), and even specialty breads with honey, cheese, or olives mixed into the dough.

Bread was often eaten with cheese, wine, or fruit, forming the basis of most meals. In poorer districts, bread was so central that the government eventually introduced a grain dole—annona—to supply subsidized grain to citizens, ensuring social stability.

The Roman Bakery: A Technological and Social Hub

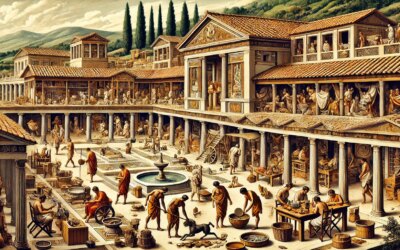

Roman bakeries, typically located on busy corners or near markets, were structured for both production and sales. Key features included:

- Large millstones (often animal-powered) for grinding grain.

- Kneading tables where dough was prepared by hand or with kneading machines.

- Wood-fired ovens—usually dome-shaped and made of brick—reaching extremely high temperatures.

- Shelves and baskets to display loaves for sale to passing customers.

Some bakeries operated as part of large commercial complexes, while others were family-run businesses. Archaeological sites like Pompeii have preserved entire bakeries, including loaves of bread carbonized in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

The Baking Process: From Grain to Loaf

Bread-making began before dawn. Bakers and their assistants ground the grain, sifted flour, mixed it with water, salt, and sometimes sourdough starter or yeast. The dough was kneaded, shaped, and scored with stamps to mark the maker or bakery—an early form of branding.

Loaves were baked in batches. Temperatures were carefully monitored by observing oven walls and adjusting the fire’s intensity. Once ready, the bread was cooled and displayed for sale, or delivered to markets, taverns, and elite households.

Who Were the Bakers?

Bakers—pistores—were typically freedmen or skilled slaves. Many rose to prominence through their trade, forming guilds and accumulating wealth. While not elite, successful bakers held important community roles. Some even became municipal officials or funded public works.

Work in a bakery was physically demanding. Slaves and hired workers handled grinding, kneading, oven tending, and customer service. In some bakeries, donkeys were used to turn millstones, guided in circles by handlers.

The Politics of Bread

In Rome, bread was not only nourishment—it was a political tool. The state-controlled grain supply and distribution to prevent unrest. Emperors from Augustus to Trajan ensured a steady grain annona flowed into the capital, sourced from Egypt and North Africa.

In times of shortage, bakers could be pressured—or coerced—to increase production or distribute bread at reduced prices. Inscriptions and reliefs from baker tombs often emphasize their civic duty as much as their trade, reflecting the respect and responsibility attached to their role.

Bread for the Military and Provinces

The Roman military relied heavily on baked goods. Soldiers on campaign were issued hardtack and loaves made from locally ground grain. Army camps sometimes included portable bakeries or contracted local providers. Bread helped sustain morale and mobility, and its regular supply was a matter of strategy.

Outside Rome, bakeries flourished in provincial cities from Gaul to Judea. These followed similar layouts but often adapted to local tastes. Roman baking techniques spread with the legions, influencing regional cuisines and food economies.

Archaeological Discoveries and Insights

Sites like Pompeii and Herculaneum provide extraordinary glimpses into ancient baking. Dozens of carbonized loaves have been recovered—round, stamped, and divided into segments, just as described in Roman texts. These loaves, alongside wall paintings and surviving ovens, bring daily Roman life vividly to light.

Inscriptions and reliefs found on the tombs of bakers—such as the Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker in Rome—celebrate the importance and pride of the profession. These monuments are both artistic achievements and tributes to a life spent feeding the masses.

From Pistrinum to Piazza

The legacy of Roman bakeries persists. Modern bread stamps, communal bakeries, and street-corner shops trace their ancestry to Roman pistrina. Techniques like sourdough fermentation and wood-fired baking remain popular. The social function of bakeries—as places of daily contact, community, and comfort—also endures.

In every golden crust and flour-dusted counter, echoes of the Roman baker’s art can still be found. In a city of emperors, temples, and senators, it was often the humble loaf that truly held society together.