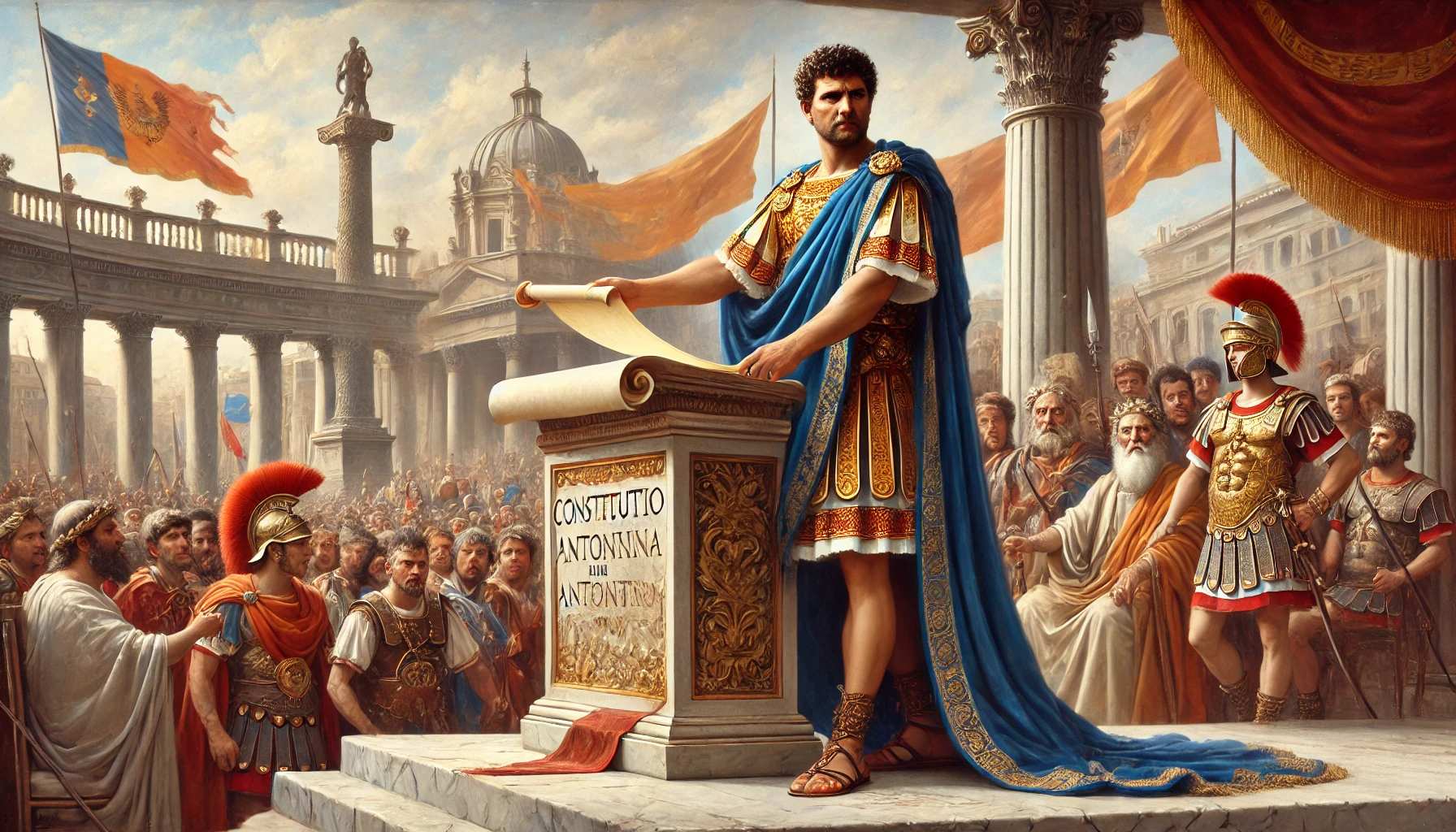

Introduction: A Scroll That Changed an Empire

In the year 212 AD, Emperor Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus—better known as Caracalla—enacted one of the most sweeping legal reforms in Roman history. The Constitutio Antoniniana, or Antonine Constitution, granted Roman citizenship to virtually all free inhabitants of the empire. What had once been an exclusive privilege became a universal right. With one decree, Caracalla redrew the map of identity, reshaping the empire’s social, legal, and cultural landscape.

Caracalla: A Controversial Reformer

Caracalla’s reign (211–217 AD) is often remembered for its brutality—fratricide, purges, and militarism—but his edict of citizenship reveals another, more complex dimension of his rule. The son of Septimius Severus and of mixed Punic and Syrian descent, Caracalla inherited a vast, diverse empire. He understood that governance over such a realm required more than military might. His edict was as much a political maneuver as a philosophical statement—a bold attempt to bind disparate peoples under a common Roman identity.

The Meaning of Roman Citizenship

Before 212 AD, Roman citizenship was a guarded status. It conferred legal protections, property rights, and tax advantages. Citizens could vote (in theory), marry legally, and appeal to imperial courts. Non-citizens—peregrini—lacked many of these privileges. Citizenship had expanded slowly over centuries through grants, military service, and colonial integration, but large swaths of the empire’s population remained excluded.

The Edict: What It Said and Did

The Constitutio Antoniniana declared that all free men throughout the empire were now Roman citizens. Women gained the corresponding legal status of cives with certain gendered limitations. This act did not abolish provincial cultures or local identities, but it legally unified the population under Roman law. The rationale cited by Caracalla was religious: he wanted all subjects to participate in state cults and sacrifices. But the motivations were also economic and administrative.

Taxation and Administration

One of the less celebrated but crucial effects of the edict was fiscal. Roman citizens paid specific taxes—especially inheritance and manumission duties. By enlarging the citizen base, Caracalla increased revenue to support his military expenditures and imperial projects. At the same time, legal uniformity simplified governance, enabling more standardized courts and bureaucratic procedures across the empire’s vast territories.

Reactions and Consequences

The edict’s reception varied. Some elites resented the dilution of citizenship’s exclusivity, while others welcomed the clarity and inclusiveness it brought. For provincials, especially those in the East, it meant upward mobility and fuller integration into Roman institutions. For historians, the edict marks a turning point—the moment Rome became a truly universal state, no longer just an Italian empire ruling foreign lands.

Long-Term Impact

The consequences of the Constitutio Antoniniana were profound. It accelerated the Romanization of provincial elites, increased the spread of Latin and Roman law, and blurred the distinction between core and periphery. It also contributed to the growing identity of Rome as a multinational, multicultural empire—a precursor to later European and Byzantine concepts of citizenship.

Conclusion: A Universal Empire

When Caracalla stood before the Senate and declared all free men citizens of Rome in 212 AD, he did more than change a law—he redefined an empire. The Constitutio Antoniniana stands as one of the most transformative acts of Roman governance, reminding us that identity, power, and inclusion are always in flux. In an age of walls and divisions, Caracalla’s decree echoes still as a radical vision of civic unity across borders.