Rome’s Most Essential Ritual of Power

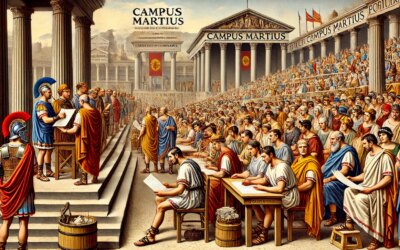

Every five years, Roman citizens would line up in solemn procession at the Campus Martius in Rome or their local forum across the provinces. They weren’t there for entertainment or religious ritual, but for a civic duty as old as the Republic itself: the census. In the 1st century AD, the Roman census was more than a population count—it was an exercise in order, identity, and the machinery of imperial rule.

What Was the Roman Census?

The Roman census was an official survey of citizens and property, originally instituted by King Servius Tullius in the 6th century BC and later reformed under the Republic. By the imperial period, it had evolved into a vast administrative operation that touched every corner of the empire.

Conducted under the supervision of censors—or by imperial officials in the provinces—the census cataloged not only population numbers but also:

- Property ownership (land, slaves, livestock)

- Social status and wealth class (used to determine voting power and tax obligations)

- Military eligibility and duties

- Citizenship claims and lineage

The process symbolized inclusion in Roman society and reinforced the intricate hierarchy of status and privilege.

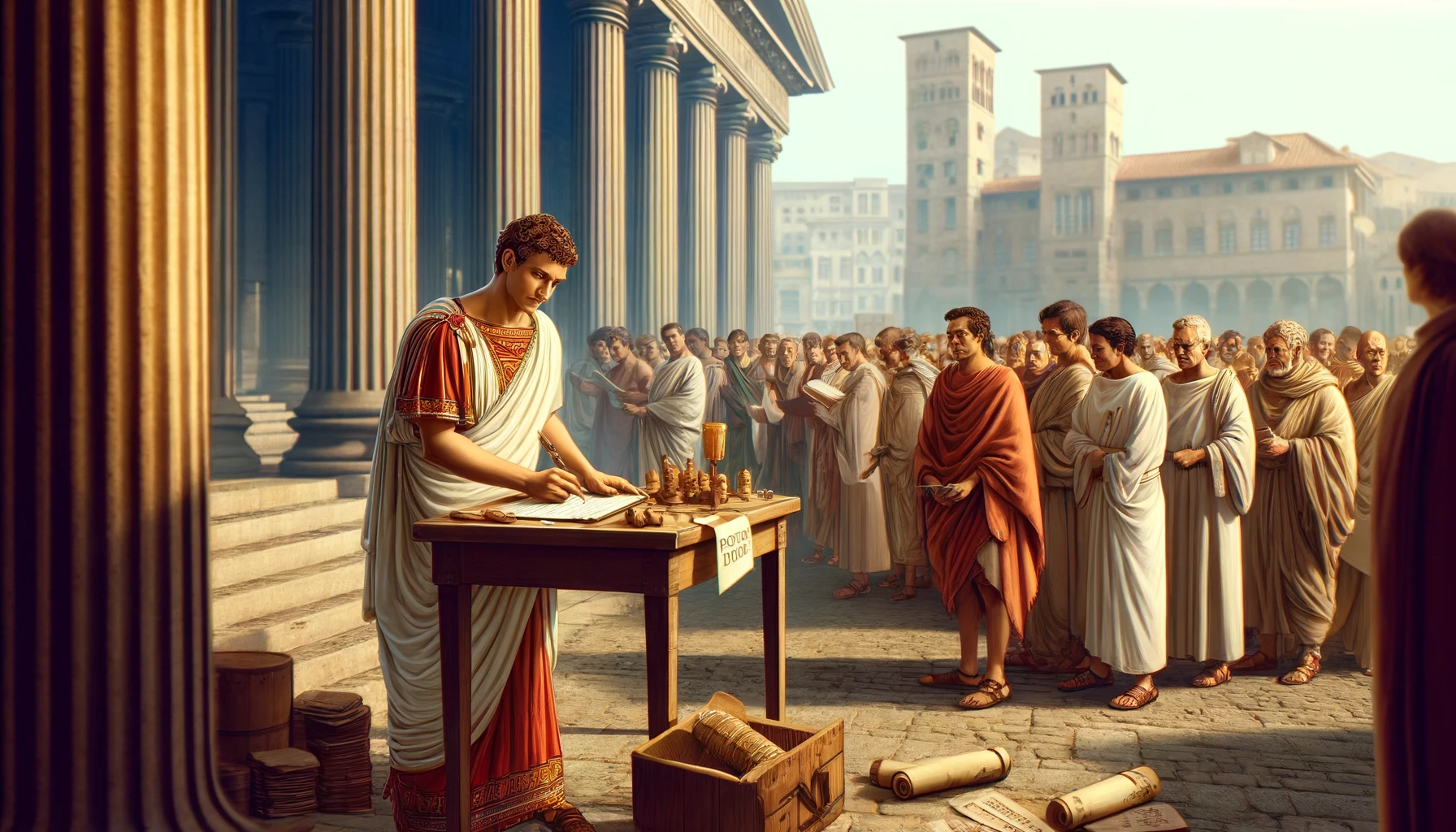

The Process of Enumeration

In the city of Rome, citizens would appear before appointed officials, often in large open spaces like the Campus Martius, to declare their family, assets, and social class. They swore an oath—professio—affirming the truth of their statements, recorded on wax tablets and papyrus scrolls by scribes.

The head of each household, the paterfamilias, was responsible for declaring information on behalf of his wife, children, and slaves. Declarations were logged, reviewed, and ultimately used to adjust tax brackets, military recruitment, and public service eligibility.

Census in the Provinces

As the empire expanded, provincial censuses became equally vital. Officials sent from Rome worked alongside local elites and governors to tally imperial subjects, especially in Egypt, Gaul, and Judaea. In fact, the New Testament account of Jesus’s birth refers to such a provincial census under Caesar Augustus.

Provincials who were not full citizens were still counted—particularly for taxation—but their legal rights and burdens varied. The census helped Rome impose uniform control across diverse cultures and territories.

Augustus and the Reforms of the Census

Under Augustus, the first emperor, the census was restructured to reflect imperial governance. He oversaw several censuses himself and instituted reforms to make the process more accurate and frequent. Census data allowed Augustus to calibrate the grain dole, military conscription, and senatorial appointments.

The emperor also used the census to promote his image as a careful steward of Roman values, tradition, and prosperity. In the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Augustus proudly recounts conducting three censuses and noting the total number of Roman citizens, presenting it as a measure of peace and order.

Tools of the Census

Roman administrators used a range of instruments to facilitate the process:

- Wax tablets for rough notes and temporary records

- Ink and papyrus scrolls for permanent storage

- Tabularia—state archives where census data was preserved

- Public inscriptions—to announce censuses or list civic responsibilities

The vast bureaucracy behind the census was a testament to Roman organizational genius. From scribes to notaries to archivists, the census employed thousands of officials, many of whom were slaves or freedmen working for the state.

Consequences of Census Results

The outcomes of a census had profound implications. Citizens might find themselves elevated to a higher voting class—or demoted due to failure to declare properly. Property declarations influenced the tribal system, military duties, and tax assessments. Dishonesty or omission could result in penalties or legal proceedings.

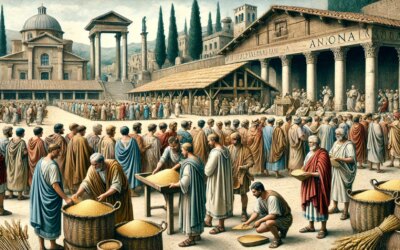

For elite citizens, census status determined eligibility for the senate or equestrian order. For the poor, inclusion in the census confirmed their right to the annona—the free grain distribution vital to survival in Rome.

Census and Social Control

The census wasn’t only administrative—it was ideological. It reminded every citizen of their place within the Roman order. The ceremony of the lustrum, held at the end of each census, involved a purification sacrifice affirming Rome’s collective moral and civic unity.

This ritual reinforced the central values of Roman identity: virtus, pietas, disciplina. The census thus functioned as both a bureaucratic tool and a political rite, underpinning the empire’s stability.

Echoes Through History

The Roman census laid the foundation for modern demographic practices. Its methods and purpose—registration, taxation, representation—remain core functions of governments worldwide. The word “census” itself comes from the Latin censere, meaning “to assess” or “to estimate.”

Though the empire has long since fallen, the impulse to count, to organize, and to govern through data remains as Roman as the toga itself.

Counting Citizens, Counting Power

The Roman census was a mirror of the empire—vast, hierarchical, meticulous. It counted people not merely as numbers, but as participants in a grand, structured society. Whether emperor or plebeian, soldier or merchant, the census asked the same of all: declare who you are, what you have, and where you belong. And in that declaration, Rome took shape—over and over again.