Introduction: An Empire in Economic Crisis

By the dawn of the 4th century AD, the Roman Empire teetered on the edge of economic collapse. Rampant inflation, currency debasement, and widespread corruption had eroded the stability of the imperial economy. Amid these challenges, Emperor Diocletian, one of the architects of the Tetrarchy, attempted a sweeping solution: the Edictum De Pretiis Rerum Venalium, or Edict on Maximum Prices, issued in 301 AD. It was one of the most ambitious price-control efforts in world history—and one of the most telling signs of imperial overreach.

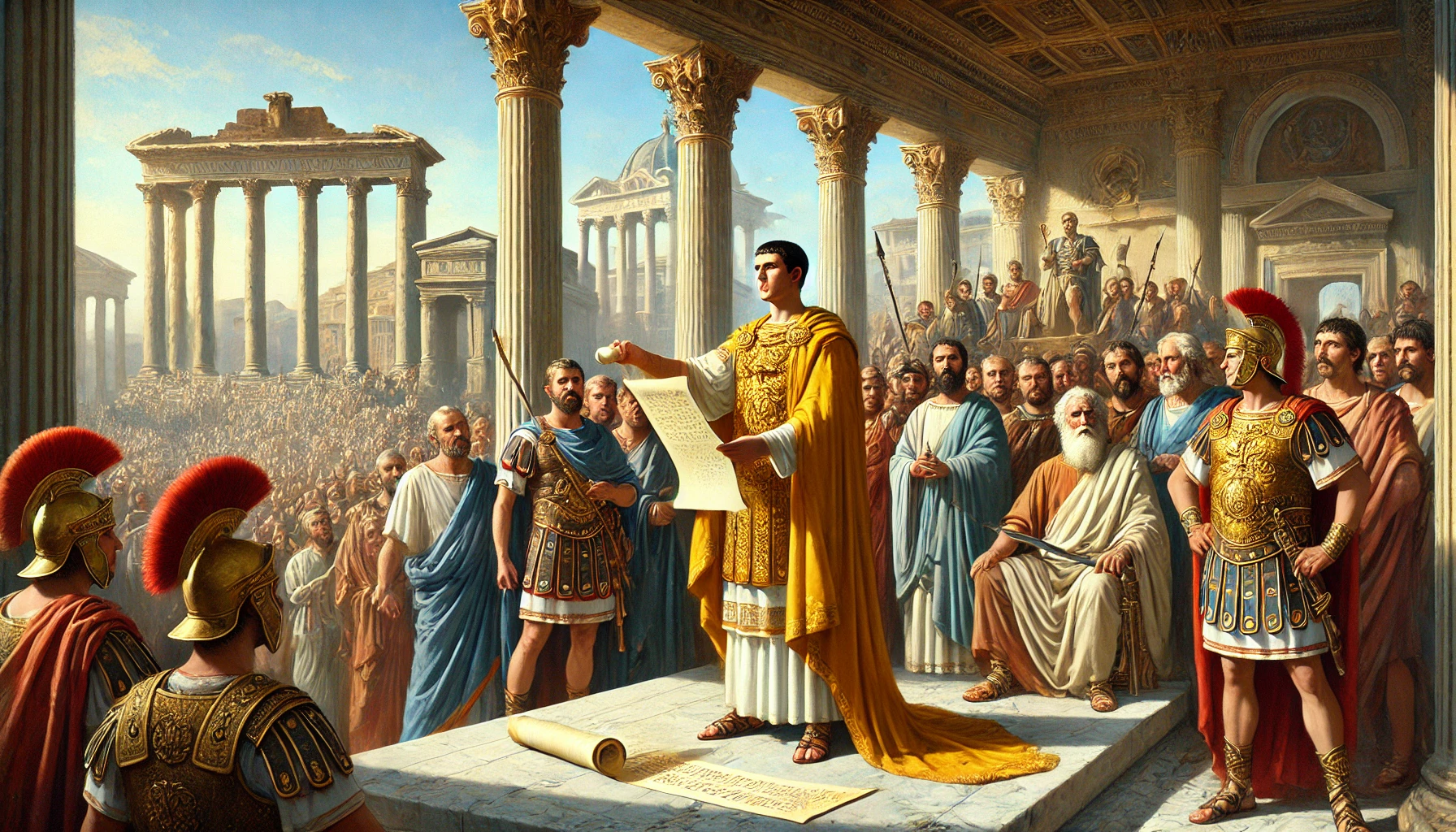

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy

Diocletian had risen to power in 284 AD after decades of internal strife and military usurpation. Determined to restore order, he created the Tetrarchy, dividing rule among four emperors to improve governance and defense. Alongside military reforms and bureaucratic expansion, Diocletian also confronted economic instability head-on, blaming greedy merchants, hoarders, and speculation for the empire’s woes.

The Problem of Inflation

Throughout the 3rd century, Rome experienced severe monetary degradation. Silver content in coins had dropped drastically, and the denarius had lost nearly all real value. Prices for everyday goods soared, soldiers demanded higher pay, and local markets devolved into barter economies. To restore confidence and halt inflation, Diocletian ordered a new coinage system—and paired it with a radical legal decree: fixed maximum prices for thousands of goods and services across the empire.

The Edict: Scope and Intent

The Edict on Maximum Prices listed over 1,000 items, including food, clothing, animals, building materials, and wages for various trades. It was inscribed on stone tablets and distributed throughout the empire. Diocletian claimed divine sanction for the act, warning that anyone who charged more than the stated maximum would be punished with death. The edict sought to protect consumers, prevent profiteering, and maintain social harmony.

Implementation and Enforcement

Enforcement of the edict proved virtually impossible. Local magistrates lacked the means—or the will—to monitor and police every transaction. Black markets flourished, goods disappeared from legal sale, and merchants often abandoned trade rather than risk execution. Ironically, the edict exacerbated shortages and further undermined trust in the economy it was meant to stabilize.

Resistance and Consequences

Public reaction varied from cautious compliance to outright defiance. In regions where the edict was strictly enforced, trade collapsed. In other areas, it was ignored altogether. Although some regions preserved inscriptions of the edict—particularly in Egypt and the Eastern provinces—the legislation had little lasting effect. By 305 AD, when Diocletian abdicated, the price controls had effectively failed.

Historians’ Judgment

Modern scholars view the edict as a reflection of Diocletian’s broader administrative mentality: centralized, moralizing, and steeped in autocratic ideology. While the intention to protect the poor and restore order was genuine, the mechanism chosen—state-imposed economic control—was ill-suited for the complex realities of a vast, diverse empire. The edict’s failure highlighted the limitations of imperial intervention in economic life.

Legacy of the Edict

The Edict on Maximum Prices stands as a milestone in the history of economic policy. It was the most extensive price control measure attempted in antiquity and remains one of the most ambitious in recorded history. Though ultimately ineffective, it provides modern historians with invaluable insight into the late Roman economy, the psychology of imperial rule, and the desperation of a state facing systemic decline.

Conclusion: Ambition in the Shadow of Decline

In 301 AD, Diocletian believed he could legislate stability into existence. His Edict on Maximum Prices was a bold, even visionary, attempt to confront a deep and complex crisis. But the limits of imperial authority—especially in economic matters—soon became clear. The emperor who divided the empire to save it, who built new capitals and reformed the army, could not conquer the invisible forces of market and mistrust. In stone and decree, his edict endures as a lesson: that even emperors cannot command prosperity by fiat.