Dining as Display: The Roman Convivium

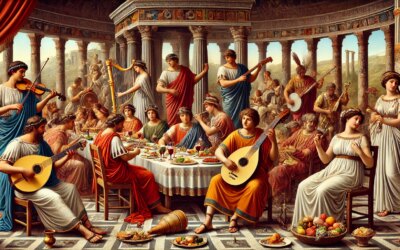

The scent of roasted game and spiced wine fills a richly frescoed dining room. Reclining on cushioned couches, Roman elites sip mulsum while listening to music played on lyres and flutes. Slaves move silently between the tables, offering platters of oysters, dormice, and figs. This is a convivium—a Roman banquet in the 1st century AD—where food and drink were more than sustenance. They were instruments of power, prestige, and cultural performance.

The Anatomy of a Banquet

A Roman banquet was typically hosted in a triclinium, a dining room with three couches arranged around a low table. Guests reclined on their left sides, propped by pillows, while eating with their right hands. Each couch seated three diners—an arrangement symbolic of Roman order and hierarchy.

The convivium was more than dinner; it was a ritualized event with rules and expectations. Guests were chosen carefully, seated by status, and entertained with music, poetry, or even political discussion. The host’s generosity—and taste—was on full display.

Food Fit for the Elite

Roman elite cuisine was diverse, experimental, and theatrical. Dishes were chosen not just for taste, but for novelty and display:

- Appetizers: Eggs, oysters, vegetables, sausages

- Main Courses: Roasted peacock, boar, fish, dormice stuffed with pine nuts and honey

- Desserts: Fresh fruits, pastries, sweetened cheeses, dates with almonds

- Condiments: Garum (fermented fish sauce), vinegar, honey, herbs

Meals were prepared by household cooks or professional chefs—often highly skilled slaves. Recipes were recorded in works like Apicius, offering a glimpse into Rome’s gastronomic sophistication.

Wine and Conversation

Wine flowed freely, always diluted with water and served in ornate vessels. Drinking customs were tightly linked to etiquette. A symposiarch or “master of the feast” regulated the strength and pace of drinking.

Toasts were frequent, and the topics ranged from love to literature, from the emperor’s latest decree to gossip about senators. Poets like Horace and Martial captured the mood of these events in witty verses that celebrated—or mocked—elite indulgence.

Entertainment and Atmosphere

No Roman banquet was complete without entertainment. Music was provided by hired performers—flute girls, harpists, and singers. Some banquets included readings of epic poetry, philosophical debates, or erotic dances.

Lighting came from bronze or terracotta oil lamps. Walls were decorated with mythological frescoes, mosaics, and sculptures. The visual and auditory environment was curated to impress and stimulate the guests.

Women at the Table

Unlike Greek symposia, Roman banquets included women—wives, mistresses, courtesans—depending on the host’s circle. Some women were celebrated hosts themselves, known for their wit, charm, and influence. The inclusion of women marked a more inclusive social dynamic within elite Roman life, though it remained structured by class and patriarchy.

Slavery and Service

Behind the opulence stood an invisible workforce. Slaves—ministri—prepared the food, poured wine, fanned guests, and cleared dishes. Others entertained or managed the household. Their labor sustained the elegance and luxury of the convivium.

Some slaves specialized in tasks such as carving meat tableside or interpreting guests’ subtle gestures. Their training and discretion were vital to maintaining the banquet’s smooth choreography.

Politics at the Table

Banquets were also arenas of influence. Alliances were forged, favors exchanged, and reputations made or broken over shared dishes. Hosts expected loyalty or political support in return for hospitality. A well-timed invitation could be more persuasive than a Senate speech.

Emperors hosted monumental feasts to assert their beneficence, while rival aristocrats competed through extravagance. The convivium was not only a celebration—it was a contest of cultural dominance.

Criticism and Satire

Not everyone admired the banquet’s excesses. Satirists like Juvenal and Petronius lampooned gluttonous hosts and vulgar displays of wealth. Their works reveal a moral anxiety about luxury and decline in Roman society, even as they indulged in its pleasures.

Banquets, they argued, had become disconnected from virtue and simplicity—symbols of a decadent Rome drifting from its republican roots.

The Echoes of the Roman Table

The legacy of the Roman convivium lives on in Western dining customs—from formal banquets to the concept of the dinner party. The idea that meals should foster conversation, culture, and community is deeply Roman.

Today, ruins of triclinia, mosaics of feasts, and surviving recipes remind us that how a civilization eats is how it lives—and how it tells its story.