The Bread of Empire

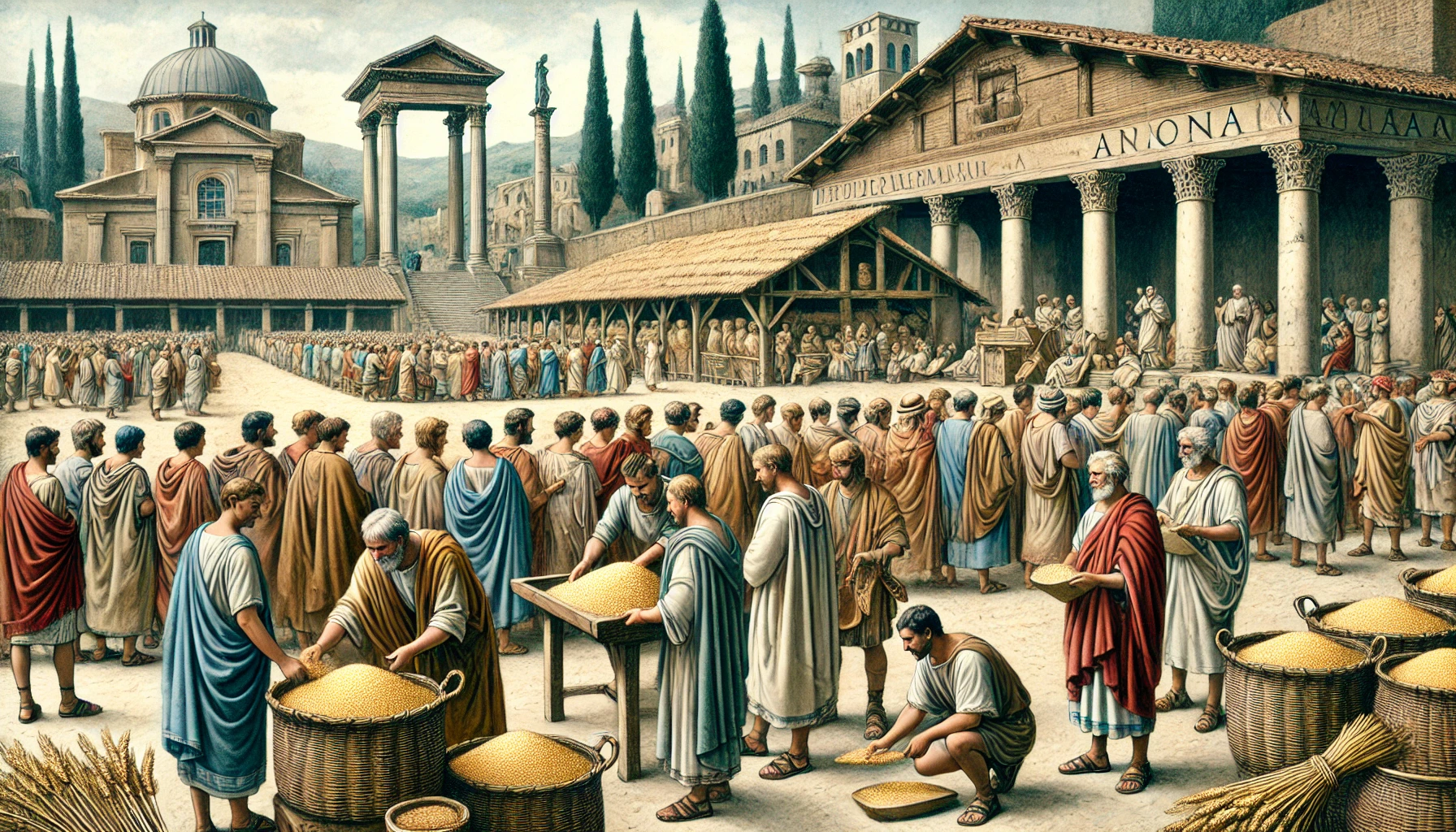

In a bustling square near the Forum, lines of Roman citizens snake past granaries, waiting their turn to receive a monthly allotment of grain. Officials with scrolls verify names, clerks weigh sacks, and baskets overflow with wheat. This is the annona—the Roman grain dole in the 1st century AD—a cornerstone of imperial welfare and urban survival.

The Origins of the Annona

The practice of distributing grain to Rome’s citizens originated during the late Republic, around 123 BCE, when Gaius Gracchus introduced subsidized grain sales as a populist reform. Over time, this evolved into a free monthly ration under Julius Caesar and Augustus, as the imperial administration sought to stabilize a capital city swollen with poor and unemployed citizens.

By the 1st century AD, under emperors like Tiberius and Claudius, the annona was an institutionalized system that provided free or heavily subsidized grain to approximately 200,000 eligible recipients—a vital mechanism for preventing famine, unrest, and political instability.

How the Dole Worked

Grain was distributed monthly or bi-monthly to male Roman citizens registered in the urban plebs. The process involved:

- Registration: Citizens were listed on rolls and issued tokens (tesserae frumentariae) authorizing collection

- Distribution points: Specific granaries and depots—horrea—were designated for dole collection

- Allotments: Recipients received a fixed amount, typically around 5 modii (roughly 35 kg) per month

- Record keeping: Clerks maintained detailed logs to prevent fraud and manage stock levels

The annona was administered by a praefectus annonae, a senior official charged with overseeing the entire supply chain—from grain procurement and storage to distribution and dispute resolution.

The Grain Supply Chain

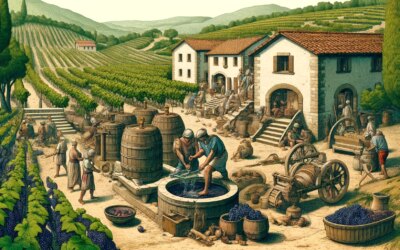

Feeding a million residents demanded a global logistical network. Grain was imported from:

- Egypt—Rome’s primary supplier after Augustus annexed it in 30 BCE

- Africa Proconsularis (modern Tunisia)

- Sicily and Sardinia

- Gaul and other provinces during shortages

The grain was transported by large merchant ships across the Mediterranean, stored in ports like Ostia, and transferred up the Tiber River by barge to massive warehouses, including the Horrea Galbae and Horrea Lolliana.

The Horrea: Rome’s Granaries

Granaries were state-of-the-art structures—multi-story warehouses with ventilation, raised floors, and fireproofing—designed to store grain safely and in large quantities. They were essential to the city’s food security and operated under strict regulation.

The largest horrea could hold tens of thousands of tons of grain, and their smooth functioning was crucial to Rome’s urban resilience. A fire, flood, or supply chain delay could trigger inflation, riots, or worse.

Political and Social Implications

The grain dole was more than a social policy—it was a political instrument. Emperors and magistrates used it to gain favor, show magnanimity, or stabilize their rule. During crises, emperors would increase rations, distribute additional goods (like olive oil or pork), or host public feasts.

The crowd in Rome—the plebs urbana—was both a power base and a threat. Keeping it fed was a matter of political survival. The annona became a symbol of imperial generosity and control.

Criticism and Controversy

Some Roman elites viewed the grain dole with suspicion or disdain. They saw it as encouraging dependency and undermining moral virtue. Writers like Juvenal and Tacitus critiqued a citizenry “content with bread and circuses,” arguing that the annona diluted Roman strength and discipline.

Despite this, few dared abolish or radically reform it—doing so would provoke unrest. The system endured because it worked, albeit imperfectly.

Beyond the Grain: Expanding Urban Welfare

Over time, the annona system expanded. Emperors introduced distributions of olive oil, wine, pork, and even money (congiaria). By the 3rd century AD, food distribution had become a complex apparatus that blended welfare, propaganda, and public order.

Even children were eventually included, especially under Christian emperors who promoted almsgiving and social care as civic duties.

The Legacy of the Annona

The Roman grain dole is often regarded as one of the first large-scale welfare systems in human history. Its scale, sophistication, and integration into state policy laid the groundwork for modern public assistance programs.

The very word “annona” lives on—in Italian and Spanish—as a term for food supply and provisioning, reminding us of its long-lasting cultural impact.

Feeding the Heart of an Empire

In the shadows of temples and columns, beneath the watchful eyes of emperors carved in stone, the people of Rome queued for their grain. What they received was more than sustenance—it was a promise that the empire would care for its own. In the weigh of each basket, the strength of the Roman state was measured—not just in legions or law, but in daily bread.