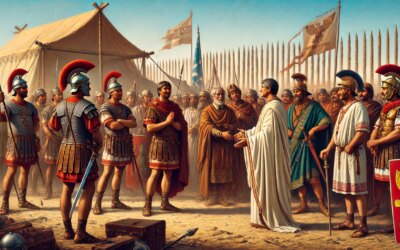

Introduction: Rome Enters the Greek World

In 196 BC, the ancient Greek world trembled on the brink of transformation. After centuries of internecine wars and Macedonian dominance, a new power had entered the stage—Rome. Yet unlike conquerors past, the Roman general Titus Quinctius Flamininus did not claim hegemony through subjugation. Instead, he stood before a crowd of Greeks gathered for the Isthmian Games and declared their freedom. This unprecedented act not only redefined Rome’s role in the East but also etched Flamininus into Hellenic memory as a liberator rather than a conqueror.

Context: The Macedonian Wars

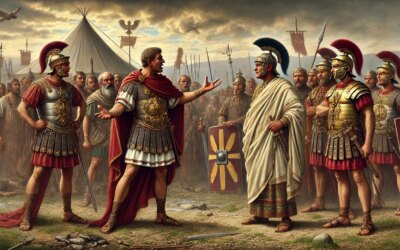

The Second Macedonian War (200–196 BC) pitted Rome against King Philip V of Macedon. Philip, ambitious and aggressive, had alarmed the Greek city-states and Rome alike with his expansionist policies. Rome, eager to curb Macedonian influence and secure its own strategic interests in the eastern Mediterranean, intervened under the pretense of defending Hellenic liberty. Flamininus, appointed commander of Roman forces in 198 BC, quickly emerged as both a military tactician and a shrewd diplomat.

The Battle of Cynoscephalae

In 197 BC, Flamininus defeated Philip decisively at Cynoscephalae in Thessaly. The battle showcased the superiority of the Roman manipular legion over the Macedonian phalanx and ended Philip’s ambitions in Greece. With the victory secured, Flamininus turned to politics—keenly aware that Rome’s image in the Greek world would shape future alliances and stability.

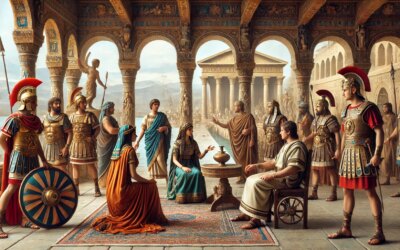

The Isthmian Games and a Proclamation

During the Isthmian Games of 196 BC, held near Corinth, Flamininus made his most memorable move. As thousands of Greeks gathered to celebrate, he ordered a herald to deliver a message that would reverberate across the Hellenistic world: “The Roman Senate and Titus Quinctius Flamininus proclaim the freedom of the Greeks… they shall live without garrisons, without tribute, and with laws of their own choosing.”

The Reaction of the Greeks

According to the historian Livy, the response was instantaneous and euphoric. The crowd erupted in cheers, unable to believe such a promise could come from a foreign power. Tears flowed, garlands were thrown, and statues of Flamininus began to appear across Greek cities. The carefully crafted message struck a chord with a people long under foreign rule. For the moment, Rome had not only won the war—it had won the narrative.

Flamininus: Liberator or Strategist?

While hailed as a hero, Flamininus was also a calculating realist. His declaration of freedom was not altruistic—it was deeply strategic. By removing Macedonian influence and avoiding overt annexation, Rome positioned itself as an arbiter and ally. Flamininus used Greek admiration to solidify Rome’s dominance without costly occupation. His gesture allowed Rome to maintain influence through diplomacy and client relationships rather than colonization.

Long-Term Implications

The freedom proclaimed in 196 BC was, in many cases, temporary. Over the following decades, Roman involvement in Greece deepened. By 146 BC, after the Achaean War, Rome would sack Corinth and formally annex much of Greece. Yet the memory of Flamininus endured. Even centuries later, his image remained prominent in Greek public life—a testament to the power of optics, symbolism, and political finesse.

Conclusion: The Moment That Changed a World

At the Isthmian Games in 196 BC, Titus Quinctius Flamininus did not raise a sword—he raised a voice. His proclamation of Greek freedom, though rooted in strategy, resonated as an act of vision and diplomacy. It marked the beginning of Rome’s complex and often contradictory relationship with Hellenic civilization. Flamininus stepped onto the field not just as a general, but as a bridge between worlds—Roman and Greek, East and West, conquest and cooperation.