Harvesting Empire: The Backbone of Roman Viticulture

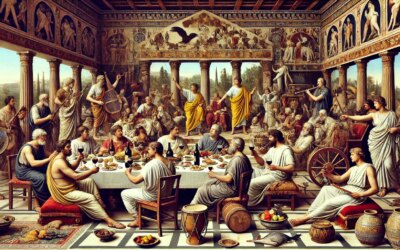

As the autumn sun warmed the Italian countryside, rows of vines hung heavy with ripe grapes. In the 1st century AD, across the sprawling estates of Latium, Campania, and Gaul, Roman slaves bent to the rhythm of the harvest, picking fruit, loading baskets, and pressing juice into vats. These vineyards were not only agricultural enterprises—they were engines of wealth, culture, and social stratification. Behind every amphora of wine poured in Roman banquets stood legions of enslaved laborers whose lives were shaped by the vine.

The Rise of Roman Wine Culture

By the early empire, wine had become a symbol of Roman identity. From the poorest citizen to the emperor himself, wine flowed as a staple of daily life. Vine cultivation spread with Roman expansion—from the hills of Italy to the shores of Hispania and the valleys of Gaul. As consumption increased, so too did the demand for mass production—and with it, a greater reliance on the labor of slaves.

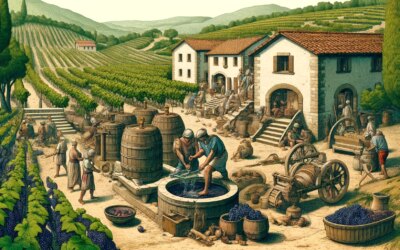

Roman villas, especially the villa rustica (countryside estate), became centers of viticultural activity. Wealthy senators and equestrians invested heavily in vineyards, often owning multiple estates dedicated to wine production for domestic use and export.

Slavery in the Roman Countryside

Unlike the better-known domestic slaves in Roman households, agricultural slaves faced grueling, monotonous labor under harsh conditions. In vineyards, tasks included:

- Pruning and training vines throughout the year.

- Harvesting grapes in large teams, often working from dawn to dusk during the short harvest window.

- Transporting grapes in baskets to the torcularia (wine press house).

- Operating presses, including manual or beam presses for juice extraction.

- Cleaning equipment and storing wine in dolium or amphorae for fermentation and shipment.

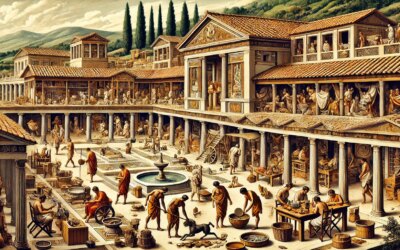

Many slaves lived on-site in barracks-like accommodations. Supervised by overseers (vilici), their days were dictated by the rhythms of agriculture and the ambitions of estate owners.

The Role of the Overseer

Overseers were often trusted slaves or freedmen charged with maintaining discipline and productivity. They managed schedules, distributed tools, and enforced quotas. Harsh punishments awaited those who slowed work, broke equipment, or disobeyed orders.

The power dynamic was strict and hierarchical. The master rarely visited during harvest—his role was to plan, finance, and reap profits, while the vilicus ensured execution.

Tools, Techniques, and Innovation

Roman viticulture employed impressive agricultural technology:

- Pruning knives and sickles for vine maintenance and harvesting.

- Wooden presses, some operated by levers and screws to maximize juice extraction.

- Clay fermentation vats and amphorae marked with vintage and estate information.

- Terraced landscapes and drainage systems to optimize sun exposure and prevent flooding.

Roman agronomists like Columella and Pliny the Elder detailed best practices in vineyard management—though such knowledge was rarely accessible to the enslaved laborers who made it possible.

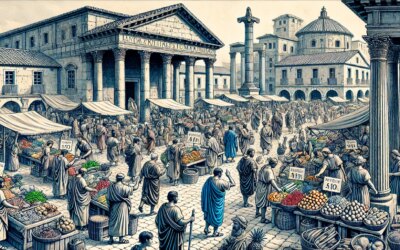

Wine as Economy and Identity

Wine was more than a beverage—it was an economic pillar. Roman wine was exported across the empire, from Britannia to Africa to the eastern provinces. The popularity of brands like Falernian or Caecuban attests to the sophistication of Roman wine commerce.

Slaves powered this trade. They didn’t just pick grapes—they created a product that crossed oceans and defined a civilization. Their work funded temples, games, and political campaigns. Ironically, while their labor fueled leisure and indulgence, their lives remained invisible in the empire’s celebratory narratives.

The Human Cost of Agricultural Wealth

While the Roman elite celebrated wine in poetry and politics, the reality for slaves was toil without respite. Disease, injury, and exhaustion were common. Runaways faced severe punishment, and legal protections were minimal. Unlike urban slaves, vineyard laborers had little chance for manumission.

Yet archaeological evidence—from slave quarters to burial inscriptions—speaks to their resilience. Some left behind names, others stories captured in epitaphs, shedding light on lives otherwise lost to history.

Legacy and Reflection

Today, remnants of Roman vineyards survive—rows of ancient vines, ruined presses, amphorae buried under centuries of soil. The wines of Europe owe much to Roman cultivation techniques, but also to the unnamed workers who made those vintages possible.

The Roman vineyard was a microcosm of the empire—advanced, productive, and deeply unequal. Its story is not just one of fermentation, but of labor, exploitation, and the enduring human spirit beneath the vine.