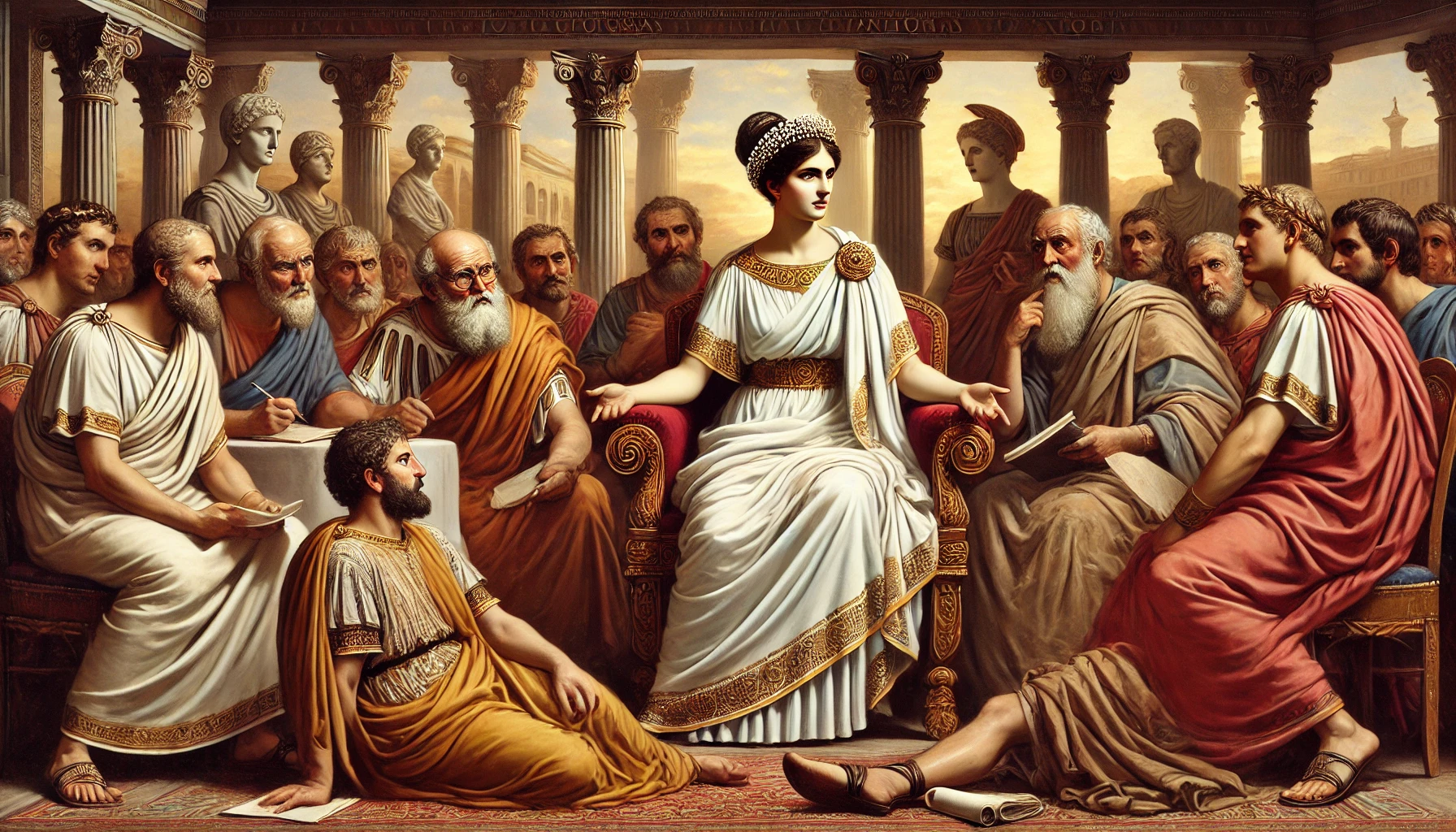

Introduction: The Philosopher-Queen of the East

In the early 3rd century AD, as Rome’s imperial power stretched from Britannia to Mesopotamia, a remarkable woman stood at the heart of its intellectual and political life: Julia Domna. As wife of Emperor Septimius Severus and mother to emperors Caracalla and Geta, she held immense influence. But it was in Antioch, around 210 AD, that she truly flourished—not as a ruler, but as a patron of minds. Her court became a haven for scholars, philosophers, and rhetoricians, blending governance with a passion for ideas.

Background: From Syria to Rome

Julia Domna was born in Emesa (modern Homs, Syria) around 160 AD into a powerful priestly family devoted to the sun god Elagabal. Her marriage to Septimius Severus in 187 AD was politically astute—uniting Roman military ambitions with eastern religious prestige. As empress, she accompanied Severus on military campaigns and participated in statecraft with a keen intellect and unshakable presence.

Antioch: Rome’s Eastern Capital

By 210 AD, Julia Domna had established a semi-permanent imperial presence in Antioch, one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the empire. There, she created a vibrant court modeled on Hellenistic ideals—a place where political advisors and literary figures mingled, and where philosophy was not a distraction from power, but its complement. Antioch under Julia was Rome’s Eastern mind, its cultural soul extending beyond military conquest.

The Circle of Julia

Julia’s entourage included luminaries such as Philostratus, the sophist and biographer of Apollonius of Tyana, and Galen, the famed physician whose writings shaped medical understanding for centuries. She supported the collection and commentary of ancient texts, funded philosophical lectures, and debated matters of state with both senators and scholars. Her court revived the classical Greek tradition of learned aristocracy—echoing Pericles’s Athens and Alexandria’s Library.

Philosophy Meets Politics

Julia Domna believed in reasoned discourse as a pillar of governance. In an era marked by dynastic feuds and military despotism, her intellectualism offered a humanistic counterpoint. She championed Stoicism and Neoplatonism, philosophies that emphasized duty, rational order, and the harmony of the cosmos—principles she sought to reflect in her administration and her personal comportment.

Personal Trials and Public Wisdom

Despite her cultural prestige, Julia’s life was shadowed by tragedy. Her son Geta was murdered by his brother Caracalla in 211 AD, and she was forced to continue as empress under a son whose tyranny grew unchecked. Yet even in grief, she remained a central figure at court, offering counsel and projecting imperial dignity. Her resilience became legendary, and her commitment to learning never waned.

The End of an Era

Julia Domna died in 217 AD, reportedly by suicide following Caracalla’s assassination. Her passing marked the end of the Severan cultural flowering and the beginning of deeper imperial instability. But her legacy endured: future empresses looked to her as a model, and the fusion of philosophy and rule she promoted inspired later thinkers from Augustine to Boethius.

Conclusion: The Mind of Empire

In 210 AD, within the marble halls of Antioch, Julia Domna stood as a rare figure in Roman history: an empress of intellect, a queen of discourse. Her court was not just a place of power, but of enlightenment—proof that in an age of emperors and legions, ideas still shaped the empire’s soul. In her legacy lies a timeless truth: wisdom, when wedded to authority, can illuminate even the darkest corridors of power.