The Public Theater of Roman Justice

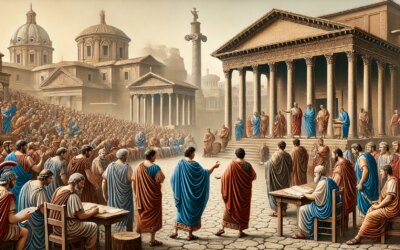

In the political heart of the Roman Republic, where laws were debated and decrees carved in stone, another spectacle unfolded—the courtroom trial. In the 1st century BCE, justice in Rome was a vivid blend of legal formality, political maneuvering, and rhetorical artistry. Courtrooms weren’t confined behind closed doors; they took place in bustling forums and basilicas, where senators, citizens, and clients gathered to witness the fate of defendants and the prowess of advocates.

Where Justice Was Served: Forum and Basilica

Trials in ancient Rome often occurred in open-air forums, beneath the colonnades of basilicas, or even at temporary platforms erected by magistrates. The most famous location was the Forum Romanum, where the Basilica Julia and Basilica Aemilia hosted numerous legal proceedings.

Here, justice wasn’t administered in hushed tones—it was a public event. Spectators watched intently, and reputations were made or destroyed. The atmosphere blended judicial solemnity with political theater.

The Players in the Courtroom

Each Roman trial was a carefully staged affair involving key participants:

- Magistrate (praetor): The judge presiding over the trial. He had the power to summon, question, and enforce judgments, though he did not always determine guilt.

- Judices: Lay jurors, often wealthy citizens, drawn from the senatorial or equestrian classes. They voted on the verdict.

- Accuser (accusator): The party bringing charges—often for political or personal gain.

- Defendant: The individual standing trial, who could be a senator, general, or common citizen.

- Advocates: Orators and lawyers, frequently from the elite, who presented arguments and called witnesses. The most famous was Cicero, whose courtroom performances remain legendary.

Scribes and assistants recorded proceedings, and witnesses testified under oath, often facing hostile cross-examination.

The Types of Cases

Roman trials covered both civil and criminal matters:

- Quaestiones perpetuae: Standing courts for specific crimes—like extortion (repetundae), treason (maiestas), or electoral bribery (ambitus).

- Private lawsuits: Including inheritance disputes, property damage, and contracts.

- Senatorial trials: High-profile political cases often heard before the Senate itself or special tribunals.

Penalties ranged from fines and exile to confiscation of property or even death, though executions were rare for elite defendants.

Rhetoric and Reputation: Weapons in the Court

Success in the courtroom depended as much on eloquence and reputation as on facts. Advocates crafted emotional narratives, appealed to Roman values, and invoked precedent and tradition. Cicero’s defense of Sextus Roscius and prosecution of Verres showcased the orator’s brilliance and turned legal cases into political statements.

Speeches were often circulated as literature afterward, solidifying careers and enshrining Roman legal values for posterity.

Law as a Political Tool

In the late Republic, trials became instruments of political warfare. Rivals brought accusations to discredit opponents. Prosecutions for corruption or treason could sway public opinion or remove threats. Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Mark Antony all used the courts strategically—either as defendants or behind the scenes.

As Rome’s institutions weakened, so did the impartiality of justice. By the 1st century BCE, bribery, intimidation, and mob influence increasingly shaped outcomes.

Legal Procedure and the Roman Mind

Trials followed structured stages:

- Initium: The accuser presented the charge to the magistrate, who approved or rejected the case.

- Nominatio judicis: Judges were selected or drawn by lot.

- Actio: Advocates presented their cases, examining evidence and witnesses.

- Sententia: Judges delivered their verdicts through a secret ballot.

While not lawyers in the modern sense, Roman advocates were often trained in rhetoric, logic, and law—skills honed in schools and sharpened in the Senate. Legal handbooks and texts, such as those by Gaius and Ulpian, began to codify legal reasoning that would shape future Roman law.

Justice for All?

In theory, Roman law applied to all citizens. In practice, status, wealth, and connections tilted the scales. Slaves could not sue free citizens; women needed guardians; non-citizens had limited rights. Yet the legal framework remained one of the most enduring legacies of Roman civilization.

The idea of written laws, due process, and public trials inspired later European legal systems and is echoed in modern courtrooms today.

The Lasting Echo of the Roman Court

Though marble courtrooms have crumbled and the voices of orators faded, Roman legal principles endure. The balance between reason and rhetoric, the presumption of law over force, and the structure of formal trials—these ideas still shape justice in the contemporary world.

In the 1st century BCE, the Roman courtroom was not just a place of judgment—it was a stage for ideas, a crucible of power, and a forum where the very meaning of justice was debated and defined.