The Pulse of Roman Entertainment

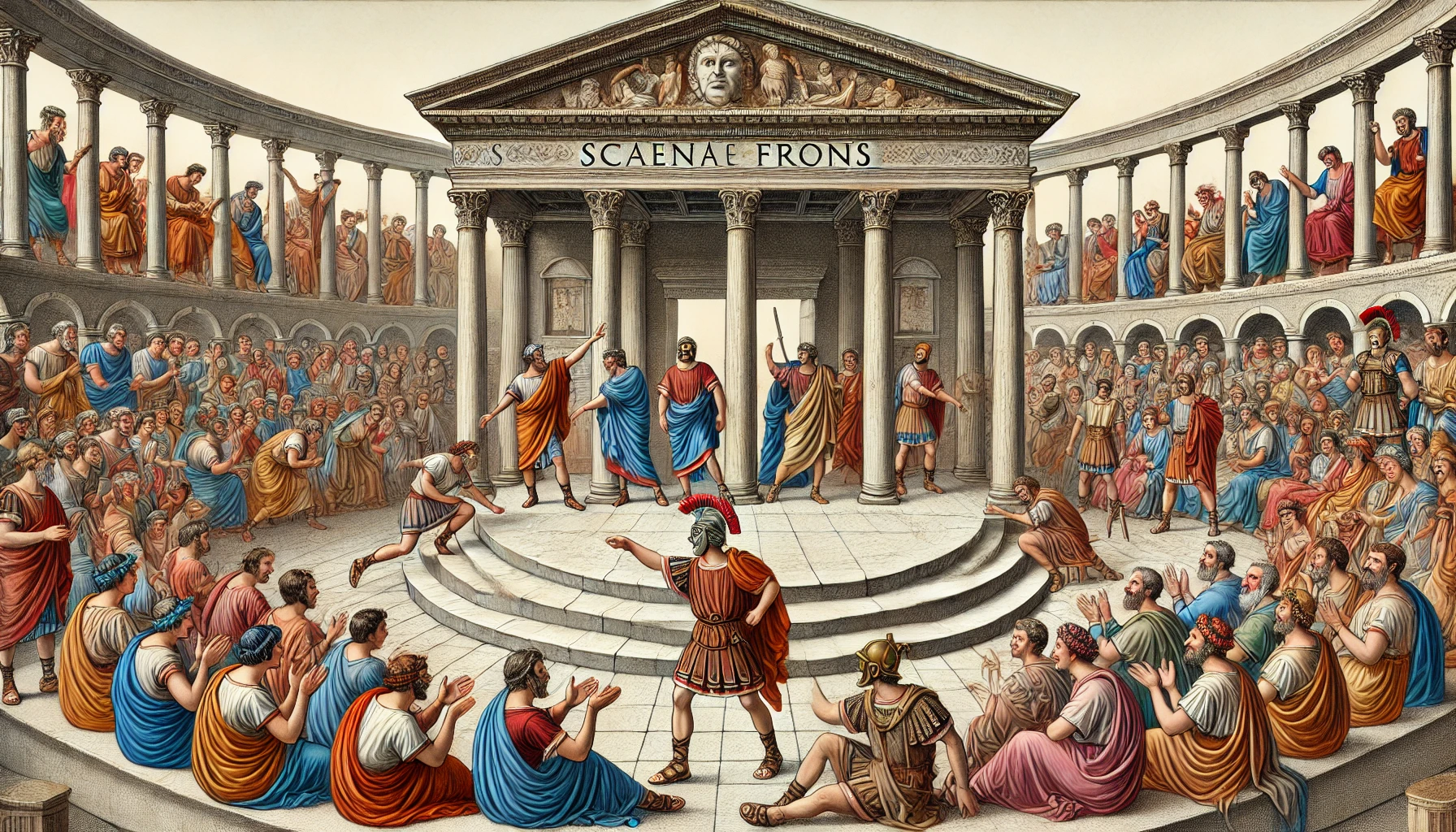

In the warm afternoon light of a Roman city, the clamor of the crowd settles as the curtain rises in a semicircular stone theater. Actors stride forward in brightly colored tunics and oversized masks, the chorus erupts in song, and the audience roars with laughter. This is the Roman comedy stage in the 1st century BC—a space where performance, satire, and civic pride converged in unforgettable spectacles of humor and humanity.

Origins and Setting

Roman theater drew heavily from Greek traditions, especially from the plays of Menander and Aristophanes. However, by the 1st century BC, Rome had developed its own style, especially in comedic genres. Theater performances were staged in large, open-air venues—initially temporary wooden structures and later permanent stone theaters like the Theater of Pompey, completed in 55 BC, the first of its kind in Rome.

These theaters were architectural feats, featuring:

- Semicircular seating (cavea) arranged by social class

- Scaenae frons, a decorated backdrop with columns and statues

- Orchestra pits used by chorus or musical performers

- Velaria, retractable awnings for shade

Capable of hosting thousands, theaters became central to civic festivals, political campaigns, and cultural life.

Genres of Roman Theater

By the late Republic, two main genres dominated Roman drama:

- Fabula Palliata: Adaptations of Greek comedies with Roman twists

- Fabula Togata: Comedies with purely Roman settings and characters

These plays were filled with stock characters—the braggart soldier, the cunning slave, the miserly old man, the scheming parasite. Playwrights like Plautus and Terence shaped Roman comedic tradition with fast-paced dialogue, wordplay, and slapstick humor.

Masks and Acting

Roman actors wore exaggerated masks made of linen or cork, with distinct features for each role—angry, happy, old, young. The mask not only clarified identity but helped project voice and emotion across vast amphitheaters. Costumes were brightly colored and stylized to match the stock roles, aiding recognition from afar.

Acting was demanding. Performers memorized long scripts, delivered lines in precise rhythm (often to music), and had to gesture dramatically to engage the audience. Though actors were not always respected socially—many were freedmen or foreigners—the best earned acclaim and imperial patronage.

The Theater as Civic Spectacle

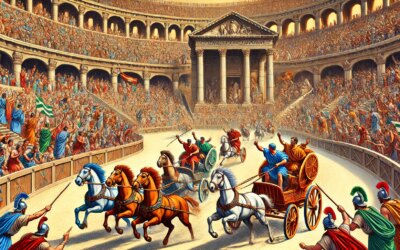

In Republican Rome, theater was more than entertainment—it was a political and social ritual. Plays were performed during public festivals such as the Ludi Romani (Roman Games), sponsored by politicians seeking popularity. Entry was free, reinforcing Rome’s tradition of bread and circuses for the populace.

Audiences were vocal, reacting with cheers, jeers, and applause. Popular actors were adored; unpopular ones booed off stage. Occasionally, plays included subversive or satirical jabs at political figures, a form of veiled critique protected under performance.

Behind the Scenes

Producing a play involved:

- Directors (dominatores) managing rehearsals and casting

- Musicians—flutists and percussionists for timing and mood

- Stagehands and prop masters handling scenery and costumes

Though few scripts survive intact, fragments, graffiti, and stage instructions show that performances were elaborately choreographed events.

Women and the Roman Stage

Unlike in Greece, women could attend Roman theater, though they sat in separate sections. Female actors existed, particularly in pantomimes or musical performances, but most speaking roles were played by men in costume and mask.

The participation of women, both as spectators and occasional performers, reveals a more inclusive, if still patriarchal, structure of Roman entertainment.

The Legacy of Roman Comedy

Roman comedic theater deeply influenced later European traditions. Medieval mystery plays, Renaissance commedia dell’arte, and even Shakespearean farce trace their roots to the masks and archetypes of the Roman stage.

Though time has weathered the stones of ancient theaters, many remain remarkably intact—testaments to the lasting appeal of public performance and shared laughter.

Echoes from the Stage

From the narrow alleys of Pompeii to the grand porticos of Rome, the voice of the Roman actor once rang clear. In every comedic twist, satirical line, and resounding ovation, the Republic expressed itself—not through decree or law, but through laughter. And long after the masks were set down and the props stored away, the theater remained—etched into Roman memory, as both mirror and mask of its people.