Where Rome’s Future Took Its First Steps

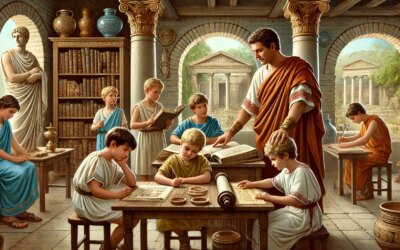

In a modest Roman room lined with frescoed walls and oil lamps, a group of children sit on wooden stools, styluses in hand. Their instructor, cloaked in a toga, reads from a scroll with slow precision as pupils inscribe his words onto wax tablets. This is a ludus—a typical Roman elementary school in the 1st century AD. Far from the grandeur of the Senate or the roar of the Colosseum, this classroom shaped the minds that would one day command provinces, plead cases, or manage estates across the empire.

The Structure of Roman Education

Roman education was deeply stratified and largely reserved for boys from affluent families. Girls typically received instruction at home, focusing on domestic skills and basic literacy, though exceptions existed among the elite. Education was seen as essential for citizenship, especially in a republic—and later, an empire—that prized rhetoric, administration, and cultural refinement.

The educational journey began in the ludus, moved through the grammaticus stage (secondary education), and culminated under a rhetor who taught the art of persuasion—a key skill for lawyers and politicians.

The Ludus and the Ludimagister

The ludus was a basic primary school where children learned to read, write, and count. It was run by a ludimagister, a teacher who was often poorly paid, socially overlooked, and required to teach large, unruly groups of students in small, rented rooms or open porticoes.

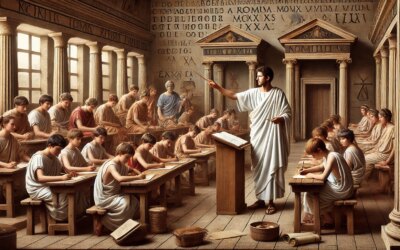

Classes began at dawn and lasted until midday. The curriculum included:

- Alphabet recitation and dictation

- Writing on wax tablets using styluses

- Memorization of moral maxims and Latin proverbs

- Basic arithmetic, often through counting boards or pebbles

Students progressed through repetition and rote learning, often accompanied by strict discipline. The ferula (rod) was a common tool of correction, and Roman writings occasionally reference beatings as a form of classroom control.

Materials of Learning

Roman students used a range of educational tools that reflected the resources of the time:

- Wax tablets: Wooden frames filled with wax served as reusable writing surfaces.

- Styluses: Metal, bone, or wooden pens used to etch letters into wax.

- Parchment or papyrus scrolls: Used for copying texts and reading literature.

- Counting boards (abaci): Used for learning arithmetic.

Reading materials often included fables, moral aphorisms, and excerpts from authors like Ennius or early Roman historians. Poetry and mythology also found their way into the classroom to inspire both style and virtue.

Discipline and Morality

Roman education emphasized moral formation as much as intellectual skill. Children were taught values like pietas (duty), fides (trustworthiness), and disciplina (discipline). Teachers were expected to correct not just grammar, but behavior.

Philosophical education would come later, but even in the ludus, the foundation of Roman ethics was laid. Through repetition of maxims, students internalized the moral architecture that supported Roman society and law.

Beyond the Classroom

For wealthier families, education continued at home with private tutors—often Greek slaves or freedmen—who provided personalized instruction in Greek language, philosophy, and rhetoric. For most, however, the ludus was the sole formal institution of learning before entry into apprenticeships or family businesses.

By adolescence, many boys would leave the classroom behind and begin real-world training. But for a select few, education opened doors to public service, legal careers, or positions in the imperial bureaucracy.

Education and Social Status

Literacy in the Roman world was a powerful marker of class. While some slaves were literate and could act as scribes or tutors, the vast majority of Romans, especially in rural areas, were illiterate. Those who passed through the ludus often belonged to the plebeian middle class or higher—families with enough wealth to invest in a child’s schooling.

Education was also a tool of cultural assimilation in the provinces. As Roman rule expanded, local elites were encouraged—or compelled—to educate their children in Roman language and values, helping to integrate conquered peoples into the imperial system.

The Enduring Legacy of Roman Education

The Roman educational model influenced countless generations. Medieval monastic schools preserved its structure, and Renaissance humanism revived its content. The image of children learning by repetition, under strict guidance, on reusable slates or tablets, persisted in European classrooms for centuries.

Modern schooling owes much to Roman pedagogy—especially in language learning, classical literature, and the idea that education forms not just the mind, but the citizen.

In Wax and Word, a Civilization Was Formed

The Roman ludus may have lacked comforts, but it shaped the thinkers, scribes, and statesmen of an empire. In dusty rooms filled with the scratch of styluses and the stern voice of the ludimagister, Roman children encountered the tools that would define their future—and the future of the ancient world. Through discipline, repetition, and the steady light of learning, they were forged not just as literate citizens, but as heirs to a civilization that believed in the power of education to rule the world.