The Whispered Rituals of Midnight Rome

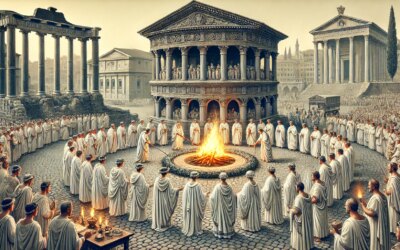

In the quiet hours of the night, when even the city’s ever-burning lamps dimmed in the silence, Roman families would gather inside their homes to confront the most intangible and unsettling of presences—the dead. Among Rome’s many sacred observances, Lemuria stands apart for its eerie intimacy and deeply spiritual undertones. Celebrated annually on May 9th, 11th, and 13th, this ancient Roman festival was not about feasting or triumph, but about fear, appeasement, and ancestral duty.

A Festival Rooted in Fear and Family

The Lemuria was believed to date back to Rome’s earliest religious traditions. According to the Roman scholar Ovid in his work Fasti, the festival was instituted by Romulus himself, in memory of his slain brother Remus. As Rome matured from a tribal kingdom to a sprawling empire, the private domesticity of Lemuria endured—a ritual deeply embedded in the identity of the Roman household.

The core belief behind Lemuria was that restless spirits of the dead, known as lemures, returned to the world of the living during these nights. These were not the honored ancestors or protective spirits (the lares and manes), but rather vengeful ghosts, unburied souls, or those whose deaths were violent or unjust.

The Pater Familias: Priest of the Household

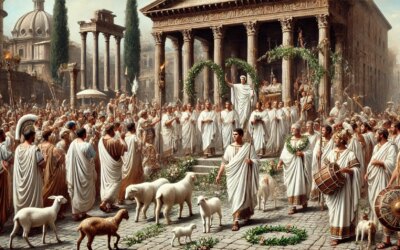

At the heart of the Lemuria was the pater familias, the male head of the Roman household. Just before midnight, he would rise barefoot and in silence. After washing his hands in pure spring water, he would walk through the darkened home and begin the ritual of expelling the spirits.

Holding black beans—symbols of mourning and spiritual appeasement—the pater familias would toss them over his shoulder, chanting nine times: “Haec ego mitto; his redimo meque meosque fabis.” (“With these I redeem me and mine.”) The beans were believed to be irresistible offerings to the dead, allowing the family to ransom themselves from the spirits’ malevolence.

While this ritual unfolded, the rest of the family would remain silent. No eye contact. No interruptions. Only when the pater familias clashed bronze pots and shouted “Ghosts of my fathers, be gone!” would the rite come to its chilling end.

Symbolism, Superstition, and Sacrifice

The Lemuria was not conducted in the temples or public squares, but within the sacred walls of the Roman domus. This distinction underscored the intimate relationship between the living and their dead. Unlike grand public festivals like Saturnalia or Lupercalia, Lemuria was introspective and secretive—much closer to what modern societies might consider spiritual or even haunted.

The black beans used in the rituals carried powerful symbolic weight. In Roman culture, black was the color of the underworld, and beans—linked to the earth—were thought to embody life and death. By casting them away, Romans figuratively “paid off” the ghosts, allowing them to rest.

No Weddings, No Fires: Lemuria’s Taboos

Because of its associations with death, Lemuria was regarded as a time of ill-omen. Marriages were forbidden during the entire month of May, a superstition that echoes in the modern Italian saying: “Maggio non ti sposare, né partire.” (“Don’t marry or leave in May.”)

Temples were closed, festivals were suspended, and even commercial activities were reduced. For three nights, Rome would dim its grandeur and retreat into the shadows of ancestral reckoning.

Lemures, Larvae, and the Roman Ghost Lore

The lemures weren’t the only spectral figures haunting Roman imagination. They were often conflated with larvae, more malevolent and chaotic spirits. These figures populated Roman nightmares, inspired cautionary tales, and warned of the consequences of neglecting burial rites or offending the divine order of the dead.

Inscriptions and epitaphs throughout the Roman world reflect this fear. Graves often featured protective curses or warnings: “Do not disturb,” “May this tomb not bring you misfortune.” Even the poor made efforts to provide proper burials, lest their souls wander restlessly after death.

A Legacy in Shadow

With the rise of Christianity in the 4th century AD, many pagan festivals were either abolished or reinterpreted. Lemuria, with its ghostly elements and pagan rituals, was too antithetical to Christian doctrine to survive. By the 6th century, Pope Boniface IV repurposed its date, transforming the pagan festival of the dead into what would eventually evolve into All Saints’ Day—another recognition of the boundary between life and death, though now sanctified by the Church.

Why Lemuria Still Resonates

Lemuria offers a glimpse into a Rome not of marble or conquest, but of superstition, family, and fear. It reminds us that even the most powerful civilization of antiquity wrestled with the unknown and the unseen. In its rituals, we see echoes of modern ghost stories, funerary customs, and our continuing struggle to make peace with mortality.

As Romans did 2,000 years ago, we too light candles for the departed, speak their names, and hope that the veil between the living and the dead, if ever crossed, remains a peaceful one.