Unleashing the Ancient Spirit of Rome

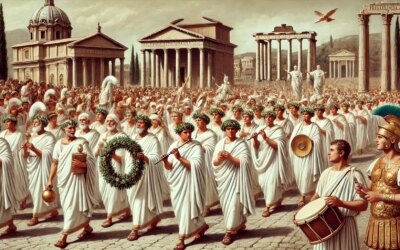

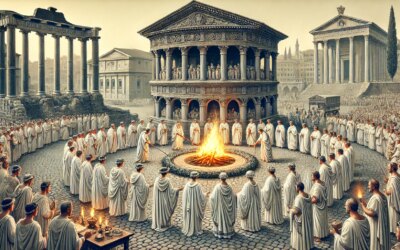

Before Valentine’s Day ever appeared on calendars, Romans in the 1st century BCE marked mid-February with a much older, more primal celebration: Lupercalia. Rooted in fertility rites, ancient myth, and community purification, Lupercalia was a wild, physical, and deeply symbolic festival that blended religious devotion with theatrical spectacle. For Roman citizens, it was both a ritual of renewal and an unforgettable street-side performance, steeped in tradition and blood.

Origins in the Cave of the Wolf

Lupercalia was held annually on February 15, with its name derived from the Lupercal—the legendary cave at the base of the Palatine Hill where the she-wolf (lupa) was said to have nursed Romulus and Remus, the twin founders of Rome. The festival honored Faunus (a rustic fertility god identified with the Greek Pan) and the Luperci, a brotherhood of priests who served him.

The rituals of Lupercalia likely date back to Rome’s earliest days, drawing on Italic and even pre-Roman traditions of animal sacrifice and seasonal renewal. While its mythic origins were revered, the celebration itself had evolved into a public spectacle by the late Republic—familiar to Romans from senators to slaves.

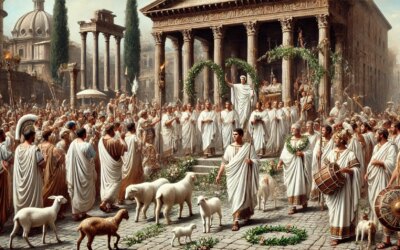

Blood, Sacrifice, and Purification

The rites began with the sacrifice of goats and a dog at the Lupercal cave by the Luperci. These animals were associated with virility and cleansing. Following the sacrifice, two young Luperci were anointed with the animals’ blood, which was then wiped clean with wool soaked in milk—a symbolic cleansing that mirrored the broader goal of the festival: to purify and revitalize the city and its people.

The Luperci then cut strips from the skins of the sacrificed goats, forming what were known as februa (from which the name “February” is derived). With these, they prepared for the most iconic part of the celebration: the race through the streets of Rome.

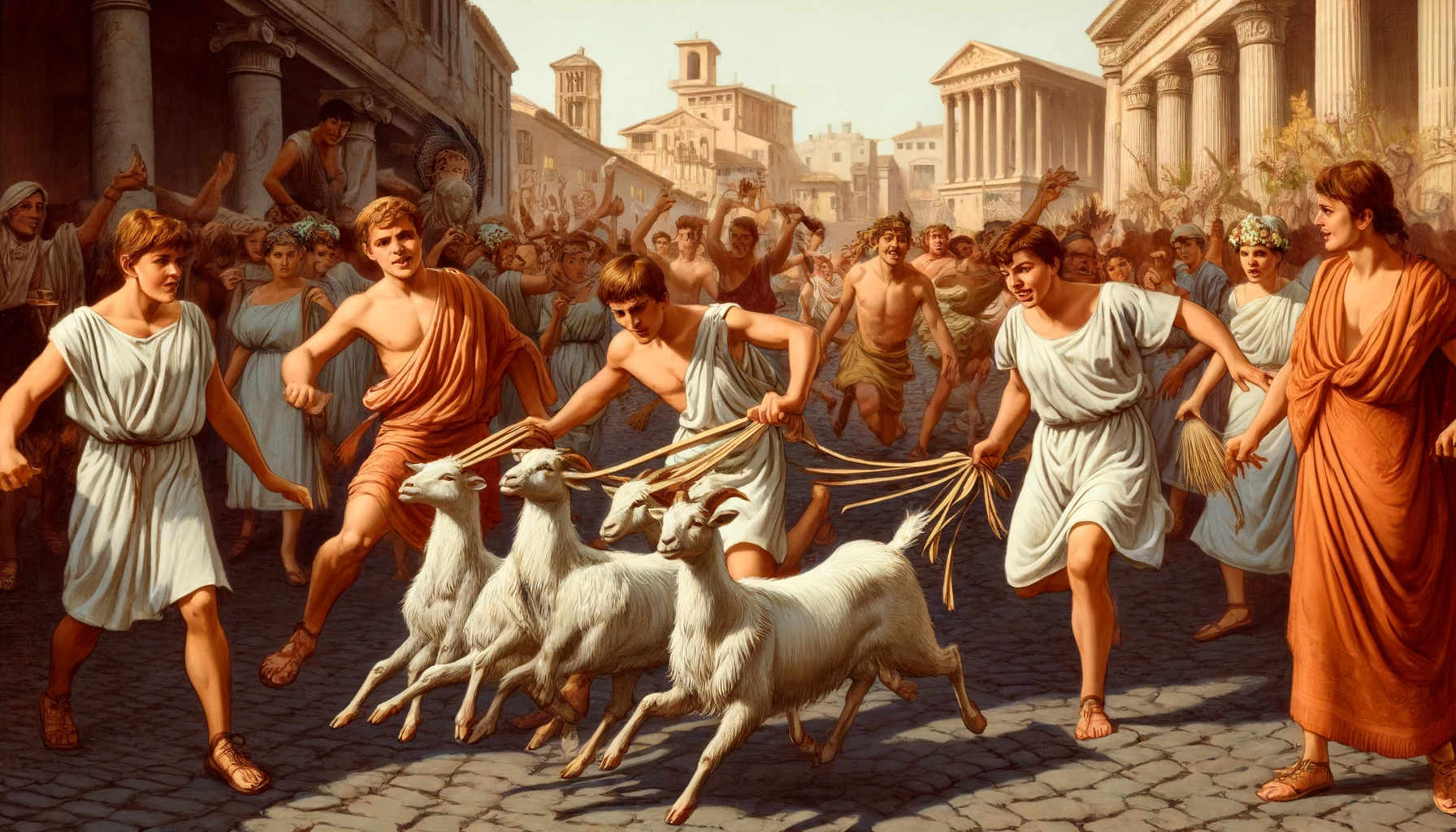

The Running of the Luperci

Clad in little more than loincloths—or sometimes naked—the Luperci raced along the Via Sacra and through the Roman Forum, laughing, shouting, and lightly whipping bystanders with their goat-hide thongs. Far from being seen as humiliating or violent, these strikes were considered blessings of fertility and purification.

Women, especially those hoping to conceive or secure safe childbirth, willingly stood in the path of the Luperci, extending their hands or baring their backs to receive the lashes. This ritualistic contact blurred the lines between sacred and sensual, divine ritual and public revelry.

Political and Social Undertones

Lupercalia also carried political resonance. In 44 BCE, Julius Caesar famously attended the festival shortly before his assassination. During that year’s celebration, Mark Antony—serving as a Lupercus—offered Caesar a crown in front of the cheering crowd, which Caesar theatrically refused. The gesture, loaded with symbolism, played into debates over Caesar’s ambition and Rome’s future. That moment would later be immortalized by Shakespeare and serves as one of the most dramatic intersections of Roman religion and politics.

The Festival in Decline

Though Lupercalia remained popular well into the Imperial period, its associations with paganism and unbridled celebration made it a target in the Christianizing era of the late empire. By the 5th century AD, Christian leaders had begun suppressing the festival. Pope Gelasius I is often credited with formally abolishing Lupercalia in 494 AD, replacing it with a more modest celebration of Saint Valentine—though the historical connection remains debated.

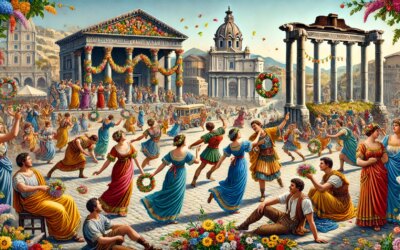

Despite its suppression, echoes of Lupercalia’s themes—fertility, romance, purification—resonate in modern Valentine’s Day traditions, even if they now wear gentler, more commercialized masks.

A Legacy of Wild Ritual and Cultural Memory

Lupercalia was more than a festival; it was an expression of Rome’s ancestral memory—of a city born from myth and nurtured by the wilderness. Its rites reminded Romans that beneath their laws, architecture, and order pulsed a more primal force: life, fertility, chaos, and renewal. In the throes of winter, Lupercalia called that force to the surface.

Today, scholars and enthusiasts revisit this ancient celebration not to revive its more unruly aspects, but to understand how deeply ritual shaped Roman identity. In a world of empire and discipline, Lupercalia was a brief, cathartic unraveling—a return to the raw vitality from which Rome itself had sprung.