Introduction: The Soldier-Emperor at War

In the turbulent year of 236 AD, the Roman Empire was ruled by a giant—literally and figuratively. Maximinus Thrax, a Thracian of humble birth and legendary stature, had risen from the ranks to become the first emperor without senatorial background. His reign was marked by relentless military campaigns, especially across the Danube frontier, where he sought to crush barbarian incursions and affirm his legitimacy through conquest. Yet his story is also one of the empire’s increasing instability, where sword and suspicion replaced Senate and tradition.

Rise of a Titan

Born around 173 AD in Thrace, Maximinus was said to stand over eight feet tall, with unmatched physical strength. His origins were humble—possibly Gothic or Alemannic—but his military talent earned him rapid promotion. In 235 AD, following the assassination of Emperor Severus Alexander by his own troops, Maximinus was declared emperor by the legions in Mogontiacum (modern Mainz). It was a break from precedent: a common soldier had seized the purple, signaling a shift in Roman politics.

The Crisis of the Third Century

Maximinus’ reign began amid mounting pressures: frontier invasions, economic strain, and political fragmentation. The Senate reluctantly confirmed his rule, though many aristocrats viewed him as a barbarian usurper. To consolidate power, Maximinus turned to what he knew best—war. The Danube frontier, always volatile, became the stage for his grand display of imperial might.

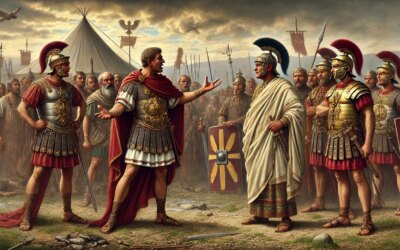

The Danubian Campaign of 236 AD

That spring, Maximinus crossed the Danube with a massive army. His targets were the Sarmatians and Germanic tribes who had taken advantage of Roman disarray. The campaign was swift and brutal. Roman sources speak of villages burned, hostages taken, and entire tribal coalitions scattered by Maximinus’ legions. He is portrayed as a tireless commander, marching through snow and forest alongside his troops, enduring hardships without luxury or pretense.

Military Glory and Domestic Discontent

Though the campaign succeeded militarily, it drained the treasury. To fund the war, Maximinus raised taxes, particularly on the senatorial class and wealthy elites. Discontent festered in Rome. The emperor never visited the capital, choosing to remain with the army on the frontier. His detachment from civilian governance and increasing autocracy alienated both the Senate and the urban population.

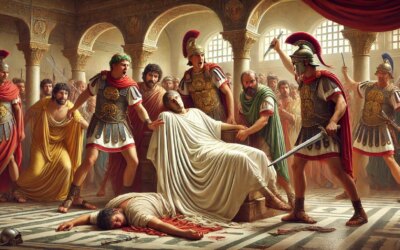

Rebellion and Decline

In 238 AD, the Senate backed a revolt in Africa, supporting the elderly Gordian I and his son as emperors. Though their rule was brief, it ignited further opposition. The Senate declared Maximinus a public enemy and elevated new emperors in his place. Maximinus marched toward Italy to reclaim control but was besieged at Aquileia. Cut off and demoralized, his troops turned on him, assassinating him and his son Maximus in the spring of 238.

Legacy of Maximinus Thrax

Maximinus’ reign was short but emblematic of the Crisis of the Third Century—a period when emperors rose and fell by military acclamation and civil war was the norm. He embodied the growing militarization of Roman politics and the erosion of senatorial influence. His physical strength and martial prowess were admired by soldiers, but his tyranny and detachment doomed his regime.

Conclusion: Strength Without Stability

Maximinus Thrax strode across the empire like a colossus, but even giants fall. His Danubian campaign, though tactically successful, highlighted the unsustainable model of imperial rule by force alone. In his towering frame, Rome found a warrior—but not a unifier. His legacy is one of brute power battling the currents of a crumbling world order, where emperors came from the barracks and died by the sword.