Sounds of Splendor: Music at the Roman Table

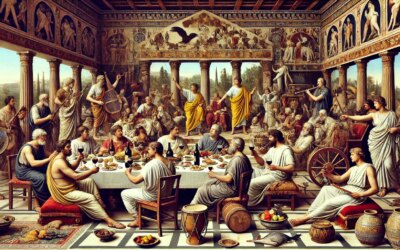

In a Roman triclinium, oil lamps flicker, frescoes glow on plastered walls, and silver platters gleam with roasted meats and sweet fruits. Reclining on couches, guests sip wine and converse in low tones. But amid the feasting, a new performance begins: musicians step forward, lyres in hand, flutes poised, ready to flood the banquet hall with melody. In the 1st century AD, music was the soul of Roman banquets, a refined art that blended culture, performance, and social signaling.

The Roman Banquet: A Cultural Showcase

Banquets, or convivia, were far more than meals—they were social theaters. The elite used them to display wealth, education, and patronage. Held in elaborately decorated dining rooms, they involved multiple courses, flowing wine, and curated entertainment. Music, in particular, played a central role in establishing the ambiance and status of the host.

Hosting musicians signaled sophistication. The presence of trained performers elevated a gathering from a mere dinner to a cultural event. Like modern gala soirées, Roman banquets became stages for personal branding, where the harmony of flutes and strings served political and personal ambition.

Instruments of the Empire

Musicians at Roman feasts employed a wide array of instruments, many inherited from Greek tradition and adapted to Roman tastes. Commonly featured were:

- Lyra (lyre): A small stringed instrument often played by women, associated with poetry and refinement.

- Tibia: A reed-based wind instrument, similar to an oboe, often played in pairs for melodic richness.

- Cithara: A large, wooden string instrument used in more formal performances, requiring skilled technique.

- Percussion instruments: Tambourines, hand clappers, and cymbals added rhythm and excitement.

Musicians tuned their instruments carefully before each performance and often improvised variations on familiar melodies. Some were slaves trained in music, while others were hired professionals who traveled from city to city seeking patronage.

Who Were the Performers?

Performers at banquets included both men and women, with many drawn from eastern provinces like Greece, Egypt, and Syria, where musical traditions were deeply rooted. Female musicians were especially popular for their grace and vocal talent, though their presence could be seen as titillating or even scandalous depending on context.

Some musicians achieved fame and prestige, performing not only at private feasts but also at public events and imperial gatherings. Inscriptions commemorate skilled artists who won favor with emperors and patrons, earning status typically denied to performers of lower classes.

Music and Mood

Roman music was closely tied to the emotional tone of the event. At the start of a banquet, soft string pieces accompanied the gustatio (appetizer course). As wine flowed, musicians might switch to livelier melodies, dances, and even comedic skits.

During philosophical or poetic recitations, background music underscored key themes. The music might also reflect the setting—a seaborne banquet could feature songs of the sea, while a springtime gathering included pastoral airs.

Musical Literacy and Elite Identity

Understanding and appreciating music was a sign of elite education. Hosts often boasted of their musical knowledge, and guests might critique performances or request specific works. Music theory was taught in rhetorical schools, and authors like Boethius and Quintilian discussed music’s moral and aesthetic value.

In this world, the ability to distinguish between a Dorian and Phrygian mode wasn’t mere pedantry—it was a signal of Roman sophistication.

The Politics of Performance

Imperial Rome used music as a tool of statecraft. Emperors such as Nero, who fancied himself a virtuoso on the lyre, performed at banquets and public spectacles. While his participation scandalized traditionalists, it underscored how deeply music had permeated Roman life and politics.

Public figures who curated musical performances at feasts could gain favor, form alliances, and assert cultural authority. The line between entertainer and elite blurred—particularly as successful performers won patronage and public acclaim.

Preserving the Sound of Rome

While no Roman sheet music survives, archaeological finds—like mosaics, frescoes, and instruments—offer clues about how music was played. Written accounts by authors like Pliny and Suetonius describe the repertoire, while reconstructions of ancient instruments have allowed modern scholars and musicians to recreate Roman sounds.

The revival of Roman music in museums and reenactments continues to bridge the gap between past and present—letting us hear echoes of a world long gone.

Echoes in the Atrium

In the laughter of guests, the clinking of cups, and the delicate plucking of lyre strings, Roman banquets revealed a civilization where art and appetite were inseparable. Music was more than entertainment—it was a language of status, pleasure, and meaning. And in its notes resounded the harmony of empire, reminding every guest that they dined not merely in luxury, but within the cultural crescendo of Rome itself.