Roads of Stone, Routes of Empire

By the 1st century BCE, the Roman Republic had stretched its arms across the Mediterranean, and with that expansion came the need for something more enduring than conquest—connectivity. Rome’s answer was its road network: straight, paved, and astonishingly durable. These roads weren’t just pathways—they were arteries of administration, movement, and military dominance. Behind each road lay a story of engineering excellence, hard labor, and imperial ambition.

The Vision and Necessity of Roman Roads

Rome’s early road projects were military in origin. The first major road, the Via Appia, was laid in 312 BCE to move troops swiftly to Samnium during the wars with the southern tribes. By the 1st century BCE, the purpose had evolved: to facilitate commerce, tax collection, political integration, and imperial communication.

As civil wars roiled the Republic—between Marius and Sulla, Caesar and Pompey—the need to move armies and supplies quickly became critical. Roads allowed Rome to react swiftly to threats, control rebellious provinces, and maintain a grip on distant lands.

The Role of Roman Engineers and Soldiers

Roman roads were designed by gromatici (surveyors) and architecti (engineers) who led teams of soldiers and laborers. Military engineers from the legions often carried out the work, supervised by commanders tasked with road building as part of provincial administration.

Surveyors used tools like the groma to align roads with mathematical precision. The Romans favored straight paths when possible, cutting through hills and spanning rivers with remarkable tenacity. Their philosophy was practical: efficiency over ease.

The Road Construction Process

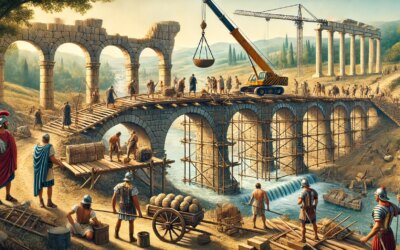

Roman roads were complex, multi-layered constructions designed to withstand time and weather. The typical method included:

- Excavation: A trench was dug along the planned route.

- Statumen: A foundation layer of large stones (about 10–12 inches deep).

- Rudus: A layer of crushed stones mixed with lime (approximately 9 inches).

- Nucleus: A finer layer of sand and gravel compacted into a firm surface (6 inches or more).

- Pavimentum: The top layer of flat paving stones, often polygonal in shape, fitted tightly together.

The entire structure was convex (cambered) to allow rainwater runoff, with drainage ditches on either side. Milestones, inscribed with distances and the names of builders or emperors, were placed regularly along the route.

Labor and Logistics

The workforce for these massive projects varied. Legionaries built roads during peacetime, gaining engineering skills and discipline. In other cases, local laborers, slaves, or prisoners of war did the digging and hauling. Materials were sourced locally, reducing transport costs but requiring smart adaptation to terrain and geology.

The coordination was impressive: construction teams set up mobile camps, transported equipment, and organized supply lines. Tools included picks, shovels, mattocks, levels, and wheeled carts—as well as basic cranes and pulleys for stonework.

Major Roads of the 1st Century BCE

By this time, many iconic Roman roads had already been constructed or extended:

- Via Appia: Extended deep into southern Italy, connecting Rome with Brundisium (modern Brindisi).

- Via Flaminia: Built in 220 BCE but heavily used during Caesar’s Gallic campaigns to access Cisalpine Gaul.

- Via Aemilia: Linked Rimini with Piacenza, uniting northern Italy’s agricultural regions.

- Via Aurelia and Via Cassia: Branched west and north, part of Rome’s vast arterial system.

These roads not only moved troops but enabled commerce, legal administration, and cultural exchange. Their economic value rivaled their military purpose.

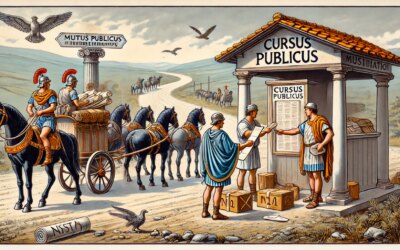

Political Messaging and Public Works

Roads also served as political propaganda. Senators and magistrates who commissioned roads left their names on milestones, emphasizing their generosity and contribution to Rome’s greatness. Caesar and Augustus both used roadbuilding as part of their public image strategies.

In the provinces, road networks showcased Roman superiority and organization, helping assimilate local populations into the empire’s framework.

The Road That Endured

Roman roads outlasted the Republic. Many were still in use during the Byzantine era and beyond. The principles of Roman road construction influenced medieval and modern infrastructure. Even today, parts of Italy and Europe still follow routes first paved in stone by Roman hands.

In total, the empire boasted over 400,000 kilometers of roads, of which more than 80,000 were paved. These roads were not just engineering feats—they were instruments of cohesion, facilitating unity across a diverse and sprawling dominion.

The Stones Beneath Empire

Beneath the clatter of Roman sandals, beneath the iron-shod wheels of ox-drawn carts, and beneath the hooves of mounted couriers, there was a system as enduring as Rome itself. These roads carried not just people and goods, but laws, letters, and loyalty. And though empires fall, some stones still bear the scars of a world once linked by lines drawn in stone.