Introduction: The Day Rome Stood Still

On a radiant September morning in 61 BC, the streets of Rome transformed into a theater of military glory. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus—known to history as Pompey the Great—was about to celebrate his third and most spectacular triumph. No Roman in living memory had conquered more, marched farther, or won more acclaim across the empire’s frontiers. His procession, winding through the city’s sacred streets, symbolized not only martial dominance but the shifting balance of power within the Roman Republic.

Pompey’s Meteoric Rise

Born in 106 BC, Pompey quickly established himself as a military prodigy. By his early thirties, he had cleared the Mediterranean of pirates, ended the Mithridatic Wars in the East, and brought vast new provinces into Rome’s fold. He was hailed as the Roman Alexander and bestowed unprecedented honors, including a peacetime triumph after his campaigns in Africa and Hispania. But his third triumph—celebrating victories in Pontus, Syria, and Judaea—eclipsed all prior pageantry.

The Path to Triumph

Following the conclusion of the Third Mithridatic War, Pompey returned to Rome in 62 BC. He had reorganized Asia Minor, deposed kings, annexed Syria, and settled scores of client kingdoms. His victories extended Roman hegemony farther east than ever before. Though politically cautious, Pompey sought recognition from the Senate for his achievements. After some delay and political wrangling, he was granted the honor of a full triumph—a celebration traditionally reserved for Rome’s greatest victors.

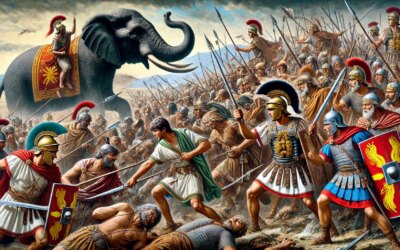

Preparations for Glory

The scale of Pompey’s triumph was unprecedented. According to ancient sources, the procession included representations of 14 conquered nations, 300 captured cities, and thousands of prisoners and exotic animals. Gold, jewels, and artworks from the East dazzled the crowds. Models of temples and fortresses were paraded alongside inscriptions boasting of lands “from the pillars of Hercules to the shores of the Euxine Sea.”

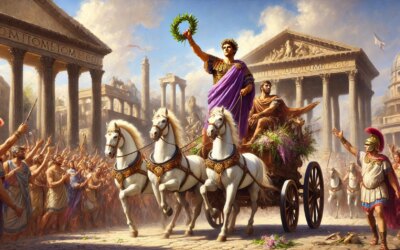

The Triumphal Procession

Pompey’s chariot was drawn by four white horses—a symbol of divine favor. He wore a golden toga, mimicking the attire of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and held a laurel branch in one hand and an ivory scepter in the other. A slave stood behind him, whispering reminders of his mortality in the ancient Roman tradition: “Memento mori.” The people roared, senators observed in silence, and the temples filled with offerings. His route ended at the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, where sacrifices sealed his supremacy.

The Political Implications

While the people adored Pompey, the Senate remained wary. His military successes had made him dangerously powerful in a republic suspicious of singular dominance. His subsequent political maneuvering—especially his uneasy alliance with Crassus and Julius Caesar in the First Triumvirate—would reshape Roman politics, contributing to the eventual collapse of the Republic. Yet in 61 BC, Pompey was still viewed as the savior of Rome’s empire, not yet its rival.

The Cultural Legacy

Pompey’s triumph set new standards for imperial celebration. Artists, poets, and historians immortalized the event. The Theater of Pompey, completed soon after, stood as a permanent monument to his glory and a cultural hub for generations. His triumph also marked a subtle shift in Roman identity—from a city-state of citizen-soldiers to an empire led by charismatic military elites.

Conclusion: The Apex of Republican Splendor

The third triumph of Pompey the Great in 61 BC was more than a victory parade—it was a declaration of Rome’s global ambition and a harbinger of change. For one day, Rome saw its future: an empire led not by consensus, but by the will of generals. Pompey stood at the height of his power, the city at the height of its pageantry. In that golden chariot, rolling through the Forum under banners and cheers, a republic celebrated—perhaps for the last time—its greatest living son.