Marching for the Gods

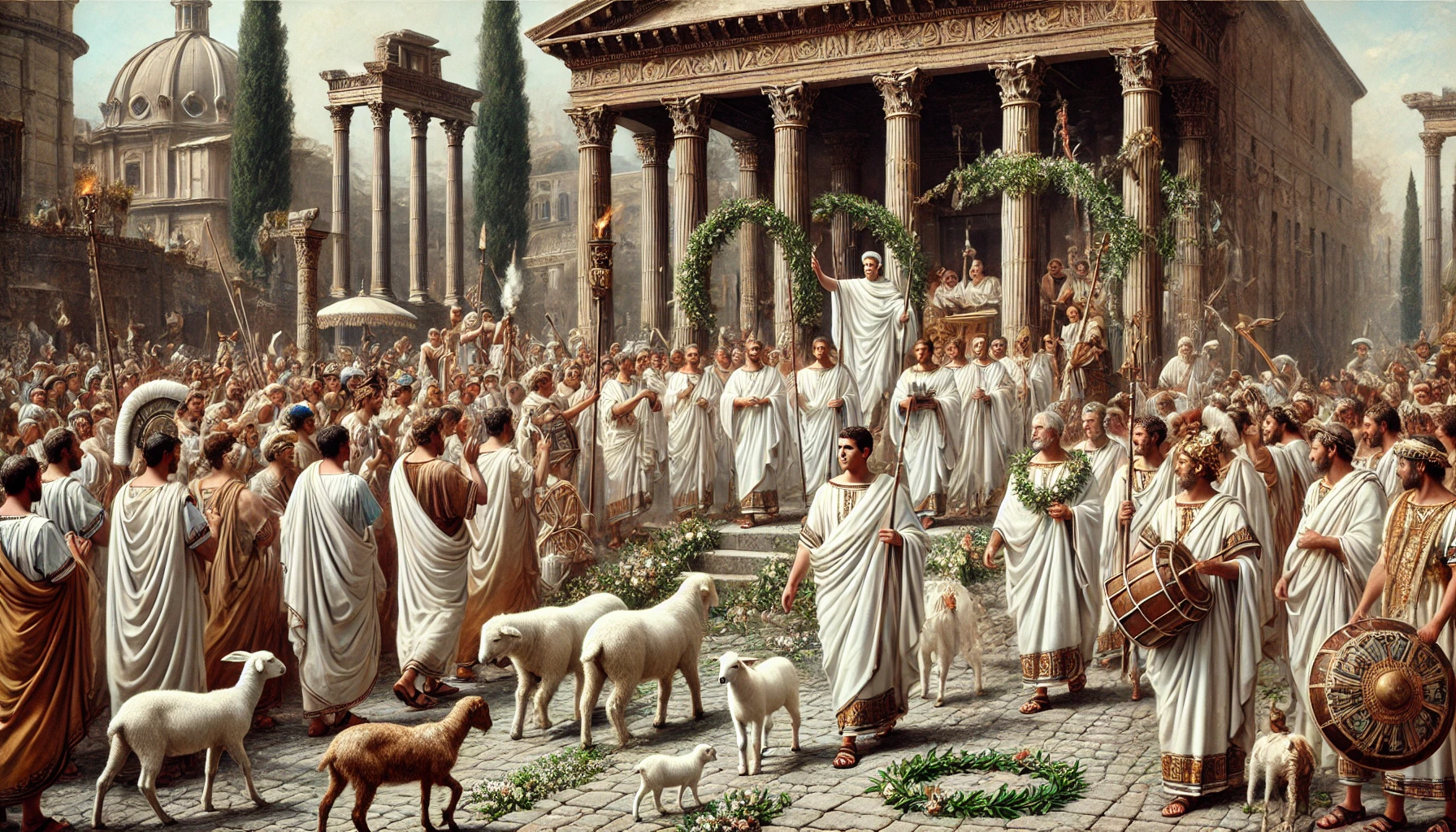

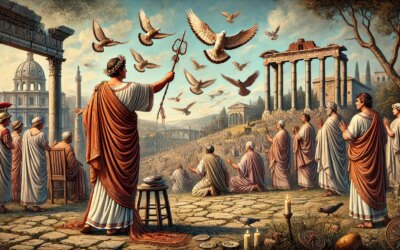

The air is thick with the scent of incense and rose petals. Horns blare, drums pound, and the solemn chants of priests echo off marble columns. At the heart of a Roman city in the 2nd century AD, a religious procession winds its way through crowded streets. This is not mere pageantry—it is a sacred performance of devotion and identity, a theater of faith where Rome’s civic and divine orders intertwine.

The Religious Landscape of the Roman Empire

By the 2nd century AD, Rome’s religious traditions were a sophisticated blend of state rituals, local cults, and imported deities. The traditional Roman pantheon—Jupiter, Juno, Mars, Venus—remained central, but new gods from Egypt, Syria, and the East had been adopted and integrated.

Religious ceremonies were not private acts of faith, but public, performative, and communal. The line between political and religious authority was blurred, and the emperor was often portrayed as divinely favored, if not semi-divine himself. Public processions were the physical expression of this spiritual and political unity.

Structure of a Roman Religious Procession

Roman religious processions, or pompae, varied by occasion—dedication of a temple, state festival, military triumph, or sacred calendar event. A typical procession included:

- Priests and Vestals: Dressed in ritual togas and garlands, they led prayers and carried sacred items

- Musicians: Trumpeters, flautists, and drummers added rhythm and solemnity

- Standard-bearers: Carried religious emblems and banners

- Citizens and magistrates: Joined in rank, wearing formal attire

- Animals for sacrifice: White bulls or sheep, decorated with ribbons and flowers

- Incense bearers and dancers: Waved censers, filling the air with fragrant smoke

Processions were carefully choreographed. Streets were cleaned in advance, and stops were made at key altars or temples for blessings and libations.

Temples and Sacred Spaces

The destination of a religious procession was often a temple or public altar. Rome’s urban landscape was rich in sacred architecture: the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the Pantheon, the Temple of Mars Ultor. These buildings were not only religious centers but also monuments of state power and artistic grandeur.

Temples were adorned with garlands, offerings, and sometimes theatrical backdrops. The culmination of a procession often involved a sacrifice (sacrificium), a communal meal, or the unveiling of a divine statue.

Ritual and Symbolism

Every element in a Roman religious ceremony was steeped in symbolism. The white toga represented purity; laurel crowns signified victory and divinity; the color red warded off evil. Priests performed augury and haruspicy, reading omens from the flight of birds or the entrails of sacrificed animals.

Even the order of the participants was significant—those with higher religious or political rank marched nearer the front. This reinforced Rome’s hierarchical but communal religious worldview.

Festivals and Calendar Events

The Roman calendar was packed with religious festivals that featured processions, including:

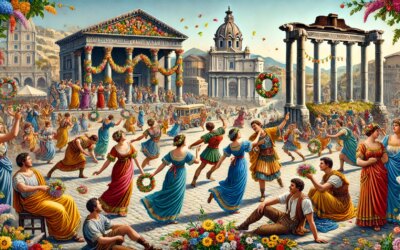

- Saturnalia: A mid-December celebration of reversal and revelry

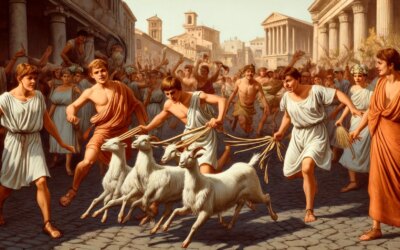

- Lupercalia: A fertility rite involving priests and public ritual

- Parentalia: Honoring ancestors with tomb-side offerings and processions

- Compitalia: Celebrating household gods (Lares) with neighborhood marches

These events often mixed sacred ritual with theatrical performance, feasting, and public games, turning the entire city into a living stage of piety and pleasure.

Imperial Religion and the Emperor’s Role

By the 2nd century AD, the emperor was not only the head of state but also Pontifex Maximus—the chief priest of Rome. Processions frequently included statues of the emperor or dedications to the Imperial cult, reinforcing loyalty and divine sanction.

Under emperors like Hadrian and Antoninus Pius, religious festivals and public ceremonies were used to project stability, piety, and continuity, especially during times of transition or unrest.

Participation and Inclusion

All Roman citizens could participate in religious processions. Even women, children, and slaves had roles—lighting torches, carrying offerings, or preparing altars. This broad inclusion gave processions a democratic appearance despite their hierarchical organization.

Non-Roman residents of the empire often watched or participated as well, especially in provinces where Roman religious rituals coexisted with local traditions.

The Echo of Ritual

Though temples now lie in ruins and processions have long ceased, the spirit of Roman religious ritual endures in Western traditions of parades, public ceremonies, and state pageantry. The integration of faith, power, and community remains a legacy of Roman religious practice.

To witness a procession in 2nd-century Rome was to see the divine made visible—gods marching among mortals, guided by incense and prayer, in a spectacle of civic unity and celestial homage.