Where Cleanliness Met Community

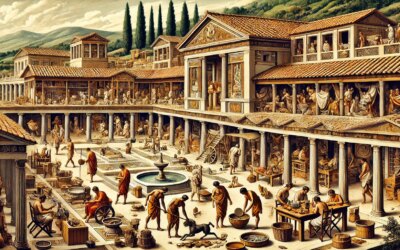

In the grandeur of ancient Rome, where aqueducts arched over valleys and the Colosseum echoed with crowds, another innovation quietly shaped daily life—public latrines. By the 1st century AD, these facilities were more than utilitarian necessities. They were feats of urban planning, sanitation engineering, and even social engagement. Roman latrines showcased how one of history’s greatest civilizations addressed hygiene with sophistication, pragmatism, and a touch of communal flair.

Why Latrines Mattered in Rome

With over a million inhabitants, imperial Rome was the largest city in the ancient world. Keeping it clean and habitable required an infrastructure that included sewers, aqueducts, and public toilets. The Cloaca Maxima, Rome’s grand sewer, had been operational since the Republic, but by the 1st century AD, the focus expanded to public comfort and widespread sanitation.

Latrines served multiple purposes:

- Improved hygiene: Reducing open defecation and disease.

- Controlled waste management: Channeling sewage into sewer systems.

- Social interaction: Functioning as informal meeting places.

- Urban equality: Making sanitation accessible to all classes, not just the wealthy.

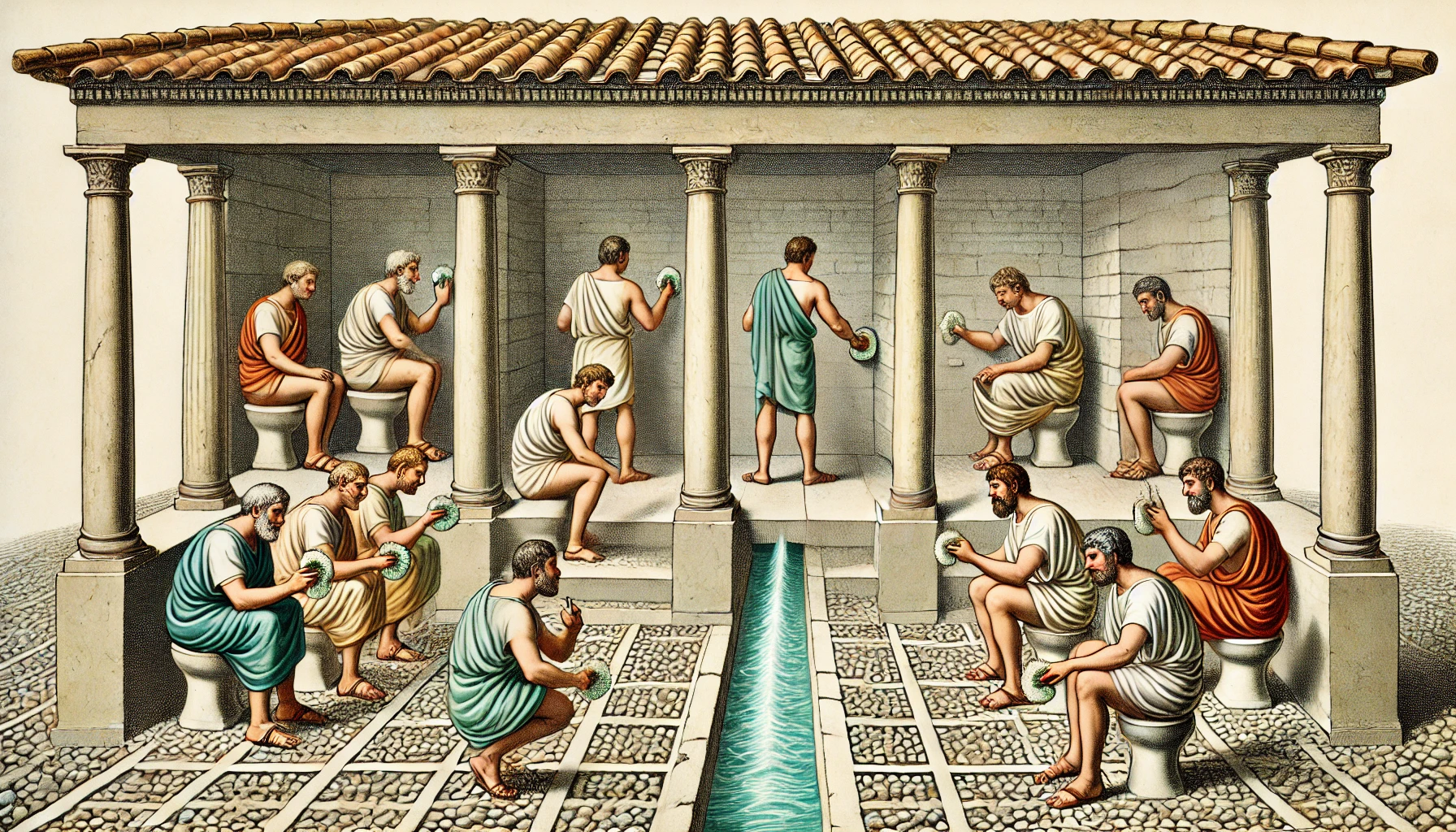

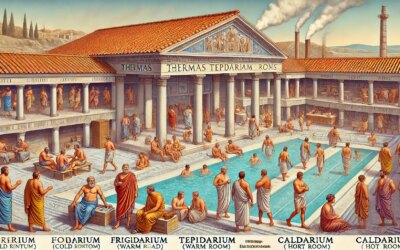

Architecture and Design of Roman Latrines

Roman latrines were carefully constructed, often as part of bath complexes, marketplaces, or along main roads. A typical layout included:

- Marble or stone benches with keyhole-shaped openings arranged along walls.

- Running water channels beneath the seats to carry waste away.

- Secondary water troughs at foot level for cleaning sponge sticks (tersorium).

- Drainage systems connected to the broader sewer network.

- Ventilation shafts and mosaic floors to reduce odor and improve aesthetics.

Some latrines could seat dozens of people at once, without partitions, emphasizing functionality over privacy. Decorations included marine motifs and inscriptions, reflecting Roman beliefs in cleanliness, health, and the natural order.

The Sponge on a Stick: Hygiene, Roman Style

Instead of toilet paper, Romans used a tersorium—a sponge attached to a wooden stick, soaked in water or vinegar. After use, it was rinsed in the trough. While the idea may raise eyebrows today, it was an effective and sustainable solution in the absence of modern hygiene products.

Use of the tersorium was communal, though wealthier citizens might have their own or use cloth. Despite lacking germ theory, the Romans displayed surprising awareness of cleanliness, relying on water flow, air circulation, and frequent flushing to maintain hygiene.

Public and Private Usage

Most citizens used public latrines, especially in densely populated insulae (apartment buildings) where private toilets were rare or rudimentary. Latrines were free or inexpensive to use, maintained by municipal workers or benefactors. Wealthier homes occasionally had private facilities, often featuring similar designs on a smaller scale.

Etiquette in latrines was informal. People talked, exchanged gossip, and debated politics. Poets like Martial and satirists like Juvenal referenced latrines in their work, indicating their ubiquity and the relaxed atmosphere they fostered.

Waste Management and the Cloaca Maxima

Rome’s impressive sanitation infrastructure ensured that latrines did not overflow or become stagnant. Waste flowed via clay or lead pipes into the Cloaca Maxima and eventually into the Tiber River. Engineers ensured proper gradients and maintenance schedules.

Regular inspections, supported by the aediles (urban magistrates), enforced cleanliness. Blockages were cleared, and repairs made to prevent disease outbreaks or foul conditions. In this sense, latrines were part of a broader commitment to public health.

Latrines Across the Empire

The Roman model was exported across the empire. Archaeological sites in Britain (e.g., Housesteads), North Africa (Leptis Magna), and the Near East (Jerash) feature remarkably similar latrine structures—testament to Rome’s standardized approach to sanitation.

In military forts, legionary latrines were positioned at the edge of camps, often near bathhouses and granaries. Efficiency, durability, and hygiene were key concerns even on the frontier.

Reliefs, Inscriptions, and Archaeology

Reliefs and graffiti in Pompeii, Ostia, and beyond show latrines as part of daily life. Inscriptions sometimes joke about their usage or commemorate builders and patrons who funded their construction. Excavated sponge sticks, latrine benches, and drainage systems have given scholars detailed insight into their function and social role.

In one Pompeian latrine, a graffiti reads: “Cacator cave malum” (“Watch out, defecator, for evil!”)—perhaps the ancient equivalent of a bathroom warning or jest.

Modern Echoes of Ancient Sanitation

Rome’s legacy in sanitation influenced medieval and Renaissance public health planning. The idea that clean cities require integrated waste systems remains foundational. The use of flowing water, public access, and municipal oversight are all principles that still govern urban hygiene today.

Though the tersorium has faded into history, the Roman latrine reminds us that civilization’s strength is measured not just in monuments—but in plumbing.