The Heartbeat of Roman Entertainment

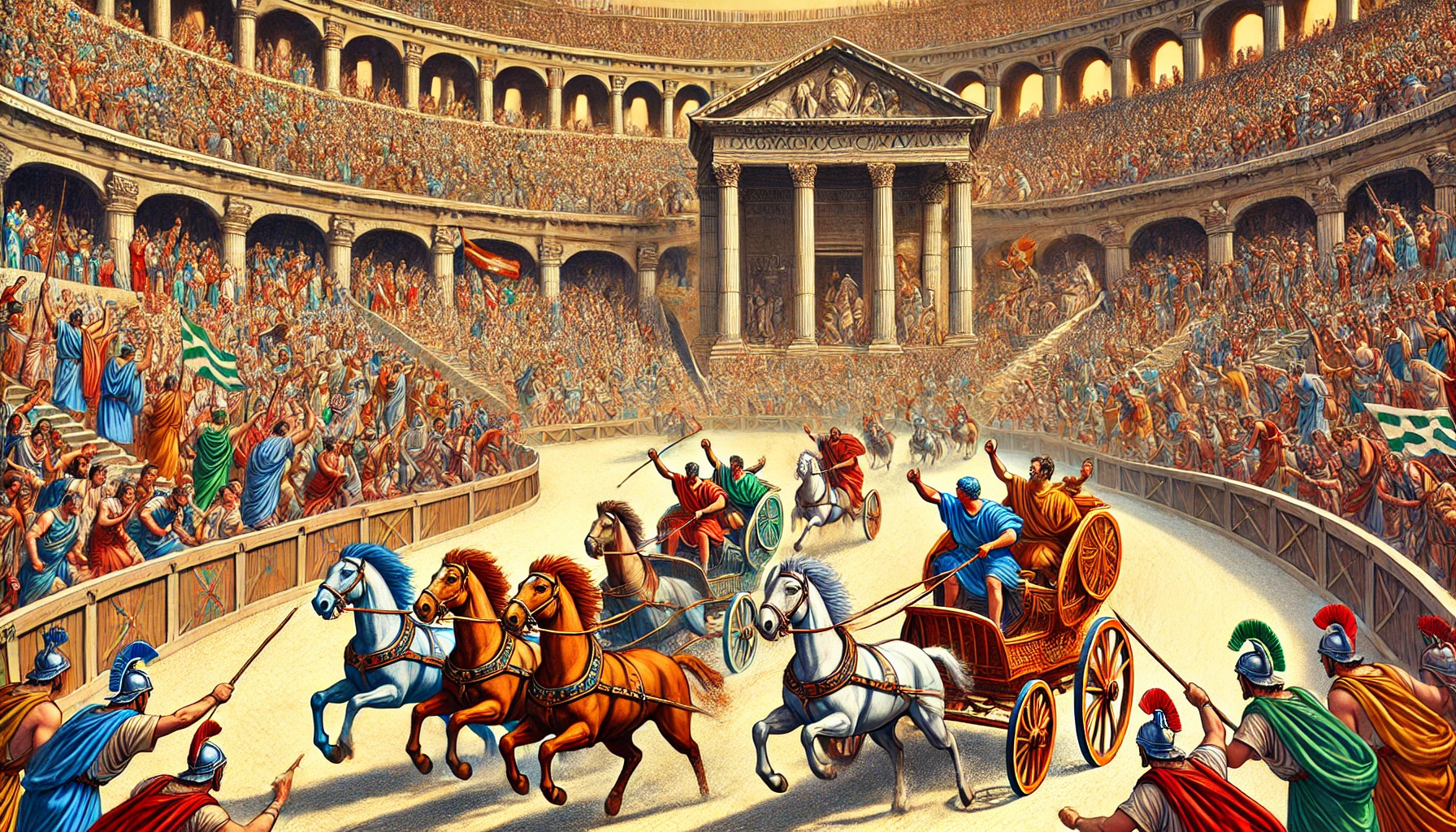

Long before the roar of crowds in modern stadiums, the Roman Empire pulsed with the thunder of hooves and the crack of whips at the Circus Maximus. Situated between the Palatine and Aventine hills, the Circus Maximus was the largest stadium in ancient Rome, capable of hosting over 150,000 spectators. At its center were the chariot races—a frenzy of color, noise, danger, and glory that captivated the Roman public for centuries. More than mere sport, these races reflected Rome’s values, politics, and obsession with spectacle.

The Origins of the Race

Chariot racing was among the oldest public entertainments in Rome, predating even the Republic. According to legend, Romulus himself used a horse race to distract the Sabines while his men abducted their women—an infamous tale tied to the founding of the city. By the 1st century AD, during the reigns of emperors like Augustus and Nero, the races had become professional, commercial, and political enterprises that dominated public life.

Structure and Design of the Circus

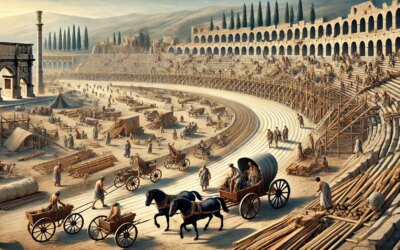

The Circus Maximus was an engineering marvel. Over 600 meters long and 150 meters wide, it featured tiered seating, multiple levels of access, and a long central spina—a barrier that divided the track and housed obelisks, fountains, and turning posts (metae).

At one end stood the carceres, the starting gates, from which up to twelve chariots would launch at once. The race typically consisted of seven laps (roughly 5 km total), each lap tracked by markers shaped like dolphins or eggs—a nod to the gods Neptune and Castor.

Factions and Fanatics

Races were not just athletic contests—they were ideological battlegrounds. Charioteers raced for color-coded teams, or factions: the Reds, Whites, Blues, and Greens. These factions commanded massive loyalty among Roman citizens, who bet on their teams, wore their colors, and fought street battles to defend their honor. By the Imperial era, emperors like Caligula and Nero openly supported factions, understanding their influence on public opinion.

The fiercest rivalry was between the Blues and the Greens. This rivalry would outlast the Western Empire and ignite riots as far afield as Constantinople, centuries later.

The Lives of the Charioteers

Charioteers, or aurigae, were often slaves or freedmen, but their fame and fortune could rival that of emperors. The most legendary of all was Gaius Appuleius Diocles, a Lusitanian who raced for 24 years, won 1,462 races, and retired with a fortune equivalent to tens of millions of modern dollars.

They raced quadrigae—four-horse chariots—guided by leather reins wrapped around their waists for greater control, a technique that made crashes (and fatalities) frequent. Sharp turns around the metae caused spectacular collisions called naufragia (“shipwrecks”), which thrilled the crowd and heightened the danger.

More Than Just a Game

Chariot races served as a form of social control and political theater. Emperors used them to gain favor, distract the populace, and project power. Tickets were free, provided by the state or generous patrons. The races often opened festivals or celebrated military victories and public holidays. During the Ludi Romani or Saturnalia, races could last for days, drawing spectators from across the empire.

Races also reinforced Roman ideals: virtus (courage), fortuna (luck), and gloria (glory). The spectacle of man and beast against danger, set in a highly structured environment, mirrored the Roman worldview—a balance of chaos and control.

The Roar Fades, but Not the Memory

By the 6th century AD, the races dwindled as the Western Roman Empire fell and Christian authorities grew less tolerant of pagan spectacle. The last recorded race at the Circus Maximus was held in 549 AD. Over time, the site fell into ruin, its marble stripped for churches and palaces. Yet the idea of chariot racing lived on in Byzantine Constantinople, and its legacy permeated literature, film, and popular culture.

Today, the outline of the Circus Maximus is still visible in Rome—a quiet park echoing the cheers of centuries past. Tourists walk where emperors sat, and the ghosts of Diocles and the Greens still race in imagination.

A Legacy of Speed and Spectacle

Chariot races at the Circus Maximus were more than games—they were the lifeblood of Roman public life, a stage where courage met risk, where the crowd ruled with roars, and where, for a few laps, glory was all that mattered. As Rome shaped the world, its greatest arena reminds us that civilization has always needed its moments of wild, glorious escape.