When Fate Was Written in the Stars

In the quiet of a Roman villa by lamplight, a figure bends over a scroll marked with celestial symbols. Outside, the night sky glimmers above the rooftops of the city. For the Romans of the 1st century AD, astrology was not merely a superstition—it was a respected, pervasive system of knowledge, one that linked cosmic patterns to earthly fate. And at the heart of this belief stood the Roman astrologer, a scholar, diviner, and often confidant to emperors and elite citizens alike.

The Rise of Astrology in Rome

Astrology was imported into Rome from Hellenistic Egypt and Babylon, where star-gazing had long served both ritual and administrative purposes. By the 1st century AD, it had become deeply embedded in Roman intellectual and spiritual life, combining Greek philosophical speculation with Eastern systems of celestial omens.

Philosophers like Posidonius and Ptolemy helped systematize astrology into a pseudo-science based on astronomical observations, while Roman thinkers adapted these ideas to their cultural framework. Astrology offered explanations for personal destiny, imperial legitimacy, and natural phenomena.

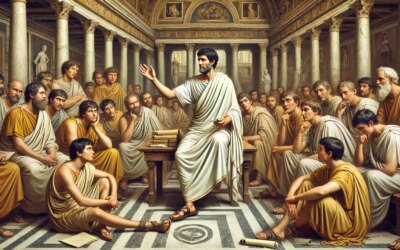

The Role of the Astrologer

Known as mathematici or astrologi, Roman astrologers occupied a unique social position. They were simultaneously feared and revered, often consulted in private by emperors, generals, and aristocrats. Their tools included:

- Horoscopes drawn from natal charts based on birth time and place.

- Ephemerides—tables tracking planetary positions and movements.

- Astrolabes and celestial globes, used to visualize the heavens.

- Papyri and scrolls filled with interpretations and diagrams of zodiacal signs and aspects.

Their consultations were often shrouded in secrecy, as emperors like Tiberius and Domitian feared their predictions—and the political implications they carried.

Astrology and the Emperors

Roman emperors were obsessed with omens. Augustus famously claimed his birth had coincided with favorable signs, while Tiberius employed personal astrologers and banned others from publishing horoscopes without state approval. The great astrologer Thrasyllus gained Tiberius’ trust by accurately predicting his rise—and by telling him he would die soon if he had not.

Astrologers could gain favor or provoke deadly suspicion. In 69 AD, the “Year of the Four Emperors,” astrological predictions circulated widely, fueling ambition and unrest. The Senate passed laws prohibiting the publication of imperial horoscopes to curb political manipulation.

Astrology and the Common Roman

Astrology wasn’t confined to the elite. Common Romans visited astrologers for guidance on marriage, childbirth, business ventures, and travel. Astrological handbooks sold in marketplaces offered simplified charts and interpretations. Zodiac rings, engraved birth signs, and planetary amulets became common adornments.

Temples incorporated celestial iconography, and household shrines sometimes included astrological symbols alongside Lares and Penates. Astrology became a shared language, helping ordinary people make sense of an unpredictable world.

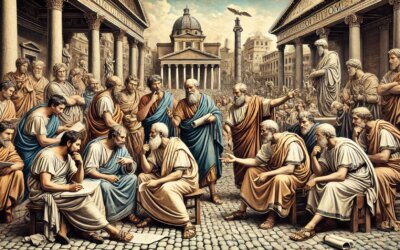

Astrology, Religion, and Philosophy

Astrology intersected with Roman religion in complex ways. Some traditionalists saw it as foreign and un-Roman, while others integrated it into existing beliefs about fate (fatum) and the divine. Stoics believed in cosmic determinism—perfectly compatible with astrology’s premise that human lives followed celestial patterns.

Others, like Epicureans, rejected astrology as irrational. Skeptical voices such as Cicero and Seneca critiqued astrologers’ reliance on vague interpretations, yet even Seneca acknowledged the emotional power of celestial contemplation.

Astrological Knowledge and Texts

Astrologers drew on a wide range of texts. Works like Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos and Manilius’ Astronomica (written under Augustus) offered poetic and technical overviews of planetary influence. The latter, in particular, cast astrology as a noble art, merging literature, astronomy, and destiny.

Tables known as ephemerides were painstakingly calculated using Greek mathematical techniques and then copied across the empire. The practice required both literacy and numeracy—skills not common to all citizens—adding to the aura of mystery surrounding astrologers.

Legacy and Transformation

With the rise of Christianity, astrology’s influence waned but never disappeared. Church fathers condemned it as pagan fatalism, yet it persisted in both private devotion and public calendars. In the Byzantine world and Islamic caliphates, Roman and Greek astrological texts were preserved, translated, and elaborated upon.

By the Renaissance, astrology returned to prominence in Europe—thanks in part to the foundations laid in Roman villas and academies. Its enduring appeal lies in its blend of observation, interpretation, and the eternal human desire to find meaning in the stars.

Celestial Maps of Power and Meaning

The Roman astrologer stood at a crossroads of belief, science, and ambition. With charts in hand and sky overhead, he dared to read the divine in planetary paths. Whether whispering to emperors or advising merchants, his art shaped lives and politics alike, proving that in Rome, even the heavens bent toward human destiny.