The Empire’s Favorite Drink

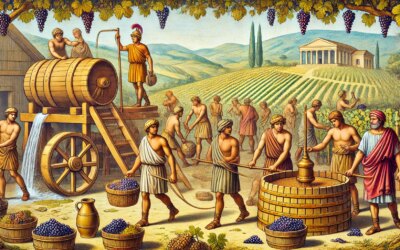

Across the rolling hills of the Roman countryside, rows of grapevines stretch toward the horizon. Laborers harvest ripe clusters, pressing them underfoot or with wooden beams into great stone vats. Amphorae are filled, sealed, and labeled for trade. This is Roman wine production in the 1st century AD—an agricultural triumph that reached every corner of the empire and shaped its social, economic, and cultural fabric.

The Rise of Roman Viticulture

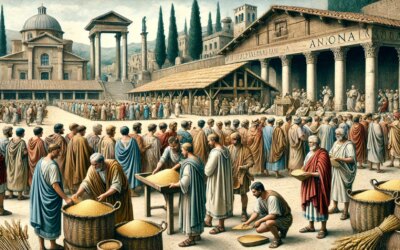

Wine was not merely a drink in ancient Rome—it was a daily necessity, a religious offering, a marker of class, and a diplomatic tool. By the 1st century AD, viticulture had expanded from its early roots in central Italy to become a cornerstone of Roman agriculture across provinces like Gaul, Hispania, and Africa Proconsularis.

Roman agronomists like Columella and Pliny the Elder recorded techniques for maximizing yields, enhancing quality, and managing estates. Their writings show a sophisticated understanding of grape varieties, soil composition, pruning methods, and fermentation.

From Vine to Vat: The Winemaking Process

Wine production followed a consistent seasonal cycle:

- Spring to Summer: Vines were pruned, tied, and maintained to encourage robust growth.

- Autumn (Vintage Season): Grapes were hand-harvested and transported to nearby villae rusticae (rural estates).

- Crushing: Grapes were pressed by treading barefoot or using mechanical wooden presses in lapides calcatorii—large stone vats.

- Fermentation: The juice was collected and stored in clay vats (dolia) or amphorae, sealed with pitch or wax.

- Aging: Wine aged in cool storage rooms. Some types were consumed young, others matured for years.

Amphorae were stamped with production details, including estate names, vintages, and quality rankings. Labels helped facilitate commerce and traceability across the Roman world.

Wine Varieties and Taste

Roman wines came in a wide range of flavors, strengths, and styles. The elite prized aged, sweetened, or spiced wines. Popular types included:

- Falernian: A strong, prestigious wine from Campania, favored by emperors and poets.

- Caecuban: Once favored by Augustus, later supplanted by other vintages.

- Mulsum: Wine mixed with honey, served as an aperitif.

- Lora: A cheap drink made from rehydrated grape skins, consumed by slaves and the poor.

Romans typically diluted wine with water—drinking it unmixed was considered barbaric. They often added herbs, resins, or sea water to alter taste and preserve freshness.

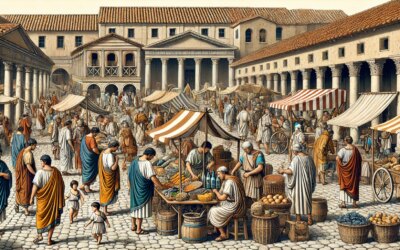

The Vineyard Economy

Vineyards were profitable ventures, especially when located near trade hubs or urban markets. A well-managed estate could produce enough wine for domestic use, local sale, and export. Viticulture also created jobs for laborers, overseers, and transporters.

Some estates specialized in premium wines and employed full-time staff, while others rented land to tenant farmers. Slave labor was common, especially on large-scale operations.

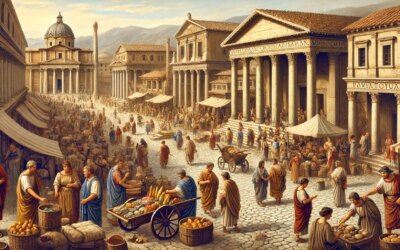

Trade and Transport

Roman wine was a key export commodity, shipped in amphorae via river, sea, and road networks. Warehouses in Ostia, Massilia, and Carthage stored vast quantities before redistribution across the empire.

Amphorae bearing the stamps of producers have been found from Britannia to the Caucasus, revealing the immense scale of Roman viticulture and trade. Some wine types became regional identifiers, promoting cultural pride and economic ties.

Wine and Roman Culture

Wine permeated every aspect of Roman life:

- In religion: Libations were poured to gods during sacrifices and feasts.

- In society: Banquets (convivia) featured wine as a centerpiece of conversation, wit, and excess.

- In medicine: Wine was prescribed for digestion, pain relief, and even wound cleaning.

- In law: Regulations governed quality control, sales, and export duties.

Even the poorest Romans consumed wine daily, making it an emblem of civilization as distinct from non-Roman “barbarian” societies, who drank beer or fermented milk.

Religious and Ritual Use

Wine held sacred value. It was offered in temples, used in funerary rites, and central to domestic rituals. The god Bacchus (Dionysus) embodied its dual nature—joy and danger, revelry and excess. Bacchic cults, though controversial, reflected wine’s deeper connection to mystery and transformation.

From Empire to Tradition

Though Rome’s political power faded, its viticultural legacy endured. Techniques, grape varietals, and trade routes established in antiquity shaped medieval and modern wine industries across Europe and North Africa. Many modern wine regions—Tuscany, Bordeaux, Andalusia—can trace their roots to Roman vineyards.

A Taste That Endures

In the clink of a modern wine glass and the aroma of aged grapes lies the memory of Rome’s agricultural brilliance. The vineyards of the 1st century AD remind us that civilization’s pleasures were once planted, pressed, and poured by hand. In every bottle that bears the trace of sun and soil, Rome’s spirit lives on.