Faith in Motion: Rituals That Marched Through the City

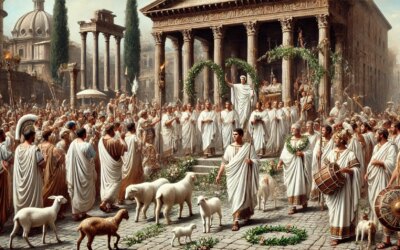

In the streets of 1st century BCE Rome, religion was not confined to temples or private altars. It moved, visibly and powerfully, through the city in the form of sacred processions—solemn marches led by priests, followed by citizens, musicians, and magistrates. These public rites, central to Roman religious life, were a blend of devotion, statecraft, and spectacle. They reminded every observer that piety was a civic duty and that the favor of the gods was vital to the Republic’s stability.

Rituals Rooted in Tradition

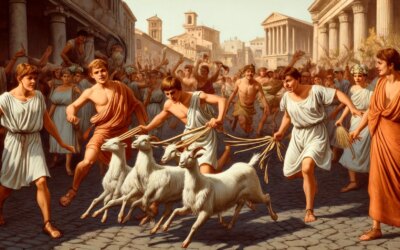

The Roman calendar teemed with religious festivals, many of which included processions through the Via Sacra, the Forum Romanum, and other public spaces. Among these were the Lupercalia, Parilia, Ambarvalia, and the Secular Games. Each had unique deities, rituals, and participants, but all shared a common form: movement through sacred space as a communal act of worship.

Processions were not mere pageants—they were solemn, orchestrated events believed to purify, protect, or honor the city. By walking together in prayer or song, the Roman people reaffirmed their bond with the divine and with each other.

The Priests and Sacred Orders

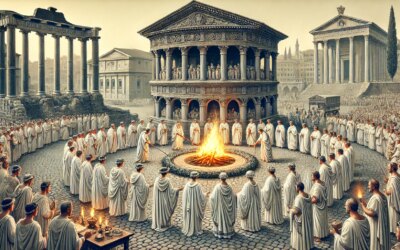

Leading most processions were Rome’s priests and religious officials, including the pontifices, augures, and flamines. Dressed in white togas with red borders, they carried sacred symbols—lituus staffs, sacrificial tools, or images of gods. The Vestal Virgins, guardians of the eternal flame, sometimes joined, particularly in rites tied to Vesta or the hearth.

One key figure was the rex sacrorum, a priestly position embodying Rome’s early monarchical religion, and the pontifex maximus, chief priest of the Roman state—held by Julius Caesar himself by the mid-1st century BCE. Their presence gave processions official weight and spiritual authority.

The Music and the Masses

No Roman procession was silent. Musicians played flutes, lyres, and curved horns, keeping rhythm as marchers advanced. Ritual chants or hymns, like the ancient Carmen Arvale, were recited by choruses of priests and acolytes. Citizens dressed in laurel wreaths or garlands followed in orderly columns—men and women, rich and poor, all united in the act of sacred movement.

Children often joined at the front, carrying torches or flowers, symbolizing renewal and purity. Slaves and foreigners were usually excluded unless specific rites allowed their participation, underscoring the Roman hierarchy even within sacred acts.

Pathways of the Sacred

Processional routes were themselves consecrated paths. The Via Sacra (“Sacred Way”) led from the Capitoline Hill, through the Forum, to the Colosseum’s future site. Along the way stood temples to Jupiter, Saturn, Vesta, and other deities—landmarks where processions paused to offer incense or prayers.

On feast days like the Armilustrium (October 19), soldiers purified their arms in the Circus Maximus. During the Lemuria, a more private ritual, families processed within homes to expel malevolent spirits. Thus, both public squares and private doorsteps became part of Rome’s living religion.

Processions as Political Theater

Religious processions also served as political displays. Leading a major festival or organizing a lavish ritual gave ambitious magistrates visibility and popular favor. Triumphs—victory parades awarded by the Senate—followed a similar form: a general paraded spoils, prisoners, and his army through the city, crowned with a laurel wreath, and followed by sacrificial rites at the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.

Even religious processions became tools of prestige and propaganda. Julius Caesar, as pontifex maximus and later dictator, used his position to shape rituals, emphasizing his connection to Venus and divine favor. Religious legitimacy became a weapon in the struggle for political supremacy.

Ritual Amidst Crisis

In times of crisis—plague, famine, military defeat—the Senate could order extraordinary supplicatio processions, calling on the gods for mercy. Citizens donned humble clothing, walked barefoot, and carried votive offerings. The entire city participated, a visible gesture of humility and hope. These events reminded Romans of their dependence on divine will and the fragility of fortune.

Priests examined omens before and after, interpreting birds, lightning, or entrails for signs of approval. If omens were unfavorable, the procession might be repeated or rituals adjusted—revealing the central role of divinatio (divination) in Roman public religion.

The Enduring Processional Tradition

Even as Christianity spread, the form of Roman processions endured. Christian liturgies adopted elements of Roman ceremonial—incense, chanting, processional crosses—rooted in the very rituals they sought to replace. In late antiquity, papal processions followed the same streets once trodden by augurs and Vestals, blending new faith with old form.

Modern parades, civic marches, and religious festivals across Europe bear echoes of the Roman ritual march—where public space became sacred through shared movement, and a city celebrated not only its gods but its identity.

The March of Belief

In the Republic’s twilight, as Rome grappled with war, ambition, and change, its processions carried something eternal. They moved not just through streets, but through the hearts of a people bound by custom, reverence, and spectacle. To follow a Roman procession was to walk with ancestors, gods, and fellow citizens—to believe, together, in the sacredness of Rome itself.