The Festival That Turned Rome Upside Down

In the depths of December, as winter shadows lengthened and the agricultural season ended, the Roman world erupted in a burst of light, laughter, and inversion. Saturnalia—Rome’s most beloved and chaotic festival—celebrated the god Saturn with a week (and sometimes longer) of feasting, role reversal, gift-giving, and social release. Held annually from December 17, Saturnalia was a vital cultural valve through which Roman society released tension and renewed community bonds, even as it mocked its own rigid hierarchies.

Honoring Saturn: From God of Seeds to Lord of Liberation

Saturn, the Roman equivalent of the Greek Cronos, was an ancient god of sowing, time, and renewal. In myth, his golden age was a time of peace, equality, and abundance. During Saturnalia, Romans tried to recapture this utopian memory through ritualized disorder. The festival began with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum, where the god’s statue—ordinarily bound with wool—was symbolically freed, signifying release from normal constraints.

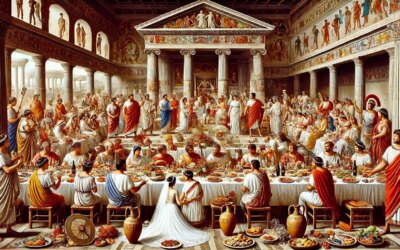

A public banquet followed, offered at the steps of the temple, kicking off days of indulgence. Throughout the city, private feasts echoed this divine revelry, with wine flowing freely and laughter echoing in villa courtyards and crowded insulae alike.

Reversal of Roles: Slaves as Masters

Saturnalia’s most famous feature was its temporary inversion of the social order. Slaves were granted freedoms unthinkable at other times of the year: they dined with their masters, spoke freely (sometimes insultingly), and even wore the pileus, a cap normally worn by freedmen. In some homes, masters served their slaves—a ritual both symbolic and performative, but one that underscored the festival’s radical turn.

This role reversal was not a rebellion but a release. It allowed for momentary equality, which paradoxically reinforced the normal hierarchy by defining its limits. Roman elites viewed the festival as a necessary indulgence that kept society stable by letting it temporarily go mad.

Customs and Celebrations

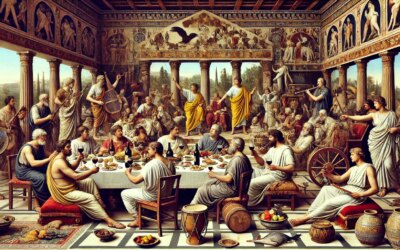

Saturnalia was marked by a series of vibrant customs:

- Gift-Giving: Small, often humorous gifts were exchanged—wax figurines, candles, dice, and poems. These sigillaria were purchased at markets held just for the occasion.

- Gambling: Normally frowned upon, gambling was permitted—even encouraged—during Saturnalia. Dice games were popular among all classes.

- Clothing Reversal: Citizens wore informal, colorful clothing instead of the sober toga. Even social appearances were turned on their head.

- Mock Kings: Many households or military units chose a “Saturnalian King”—a mock ruler who issued humorous orders and presided over revelry. This figure embodied the playful anarchy of the season.

Public spaces were decorated with greenery, garlands, and lamps. Songs filled the streets, and satirical poems circulated, often poking fun at politicians, philosophers, and societal norms.

Religious Roots and Transformation

Though Saturnalia had deep agricultural and mythological roots, by the 1st century BCE it had become a cultural cornerstone. Writers like Seneca and Martial documented its chaos with affection, even as they mocked its excesses. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus, himself a former slave, reflected on the humanity the festival momentarily restored to all people.

The emperor Augustus attempted to limit Saturnalia’s duration and public disorder, but even his power couldn’t restrain its spirit. Under Caligula, Nero, and later Domitian, the festival reached extravagant new heights, blending political theater with popular celebration.

Legacy and Echoes in Modern Culture

With the rise of Christianity, Saturnalia’s prominence declined but its customs endured. The early Church, aiming to suppress pagan festivals, eventually positioned Christmas on December 25—partly to absorb the joyful energy of Saturnalia. Elements like feasting, gift-giving, merrymaking, and even the image of a jolly man issuing decrees (Saturnalia’s king) were culturally repurposed into Christmas and New Year’s traditions.

The term “saturnalia” lives on in language as a synonym for wild celebration. Its enduring appeal lies in its duality: both a social critique and a collective exhale. Saturnalia allowed Rome to laugh at itself, to humanize the powerless, and to affirm that even in an empire of rules, joy must sometimes reign.

Memory of a Festival Eternal

Though the Roman Empire has long vanished, Saturnalia remains a glowing ember in the hearth of Western festivity. In every candlelit dinner, every exchanged gift, and every holiday toast to chaos and cheer, the spirit of Saturn’s week flickers on—reminding us that even the most serious civilizations need time to dance, to laugh, and to briefly let go.