Introduction: Empire at the Edge

In 106 AD, Emperor Trajan completed one of the most celebrated military campaigns of the Roman Empire: the conquest of Dacia. But military victory was only the beginning. What followed was a massive logistical and architectural effort to secure and integrate the new territory. At the heart of this transformation were the Roman legions, who turned battlefields into blueprints, constructing roads, fortresses, and administrative centers along the empire’s new northern frontier.

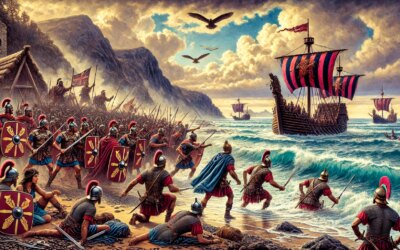

The Dacian Wars and Roman Victory

Trajan’s Dacian Wars, fought between 101–102 and 105–106 AD, brought a wealthy and strategically vital region under Roman control. Dacia, rich in gold and located north of the Danube, was both a prize and a challenge. After the defeat and suicide of King Decebalus, Rome annexed the region, creating the province of Dacia. Yet resistance from surrounding tribes and the rugged terrain meant the Romans had to act quickly to fortify their presence.

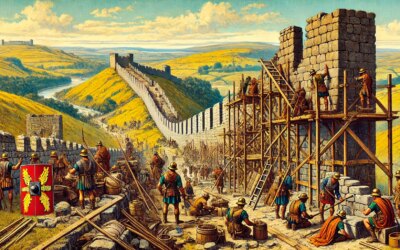

Engineering an Occupation

The Roman military wasn’t just a fighting force—it was an engine of construction. Immediately after the conquest, soldiers began building a network of forts, watchtowers, and roads across Dacia. The goal was twofold: defend the new borders and project Roman authority deep into the province. These structures were often built with both stone and timber, depending on local resources, and were typically standardized in layout for efficiency and defensibility.

Castra: The Roman Military Fortresses

At the core of Roman presence in Dacia were the castra—fortified camps designed to house garrisons, serve as supply hubs, and act as administrative centers. Forts like Apulum (modern Alba Iulia) and Porolissum became essential nodes in the provincial network. These complexes included barracks, armories, headquarters buildings (principia), baths, and even small temples. Each fortress reflected the meticulous planning and organizational power of the Roman army.

The Role of the Legions

Legions stationed in Dacia, such as Legio XIII Gemina and Legio V Macedonica, played a crucial role not just in defense but in construction. Roman soldiers were trained in masonry, carpentry, surveying, and even road-building. Under the supervision of centurions and engineers, they laid the foundations for long-term Roman rule. Veterans often settled in these areas, further Romanizing the region and contributing to its economic development.

The Strategic Importance of Dacia

Dacia was more than just a distant outpost. It formed a buffer zone against hostile tribes such as the Sarmatians and Roxolani, and its roads connected the Danube frontier with the empire’s Balkan heartlands. The integration of Dacia into the Roman infrastructure system—especially through the construction of the Via Traiana and bridge crossings over the Danube—was a masterstroke of imperial logistics.

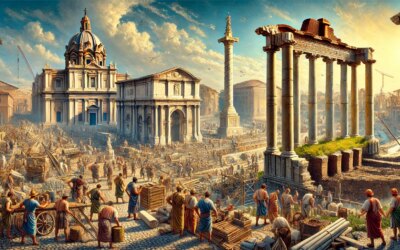

Architecture and Romanization

Roman forts became the seeds of towns. Civilian settlements—canabae—grew alongside the military camps, housing merchants, craftsmen, and families of soldiers. Temples, amphitheaters, and forums followed. These structures imposed Roman culture, language, and law onto the Dacian landscape, creating a hybrid society that would endure even after the Romans withdrew in the 3rd century AD.

Conclusion: Stone by Stone, Empire Built

The construction of frontier fortresses in Dacia after 106 AD was not just about defense—it was about transformation. Rome’s ability to turn conquest into consolidation through engineering and administration was one of its defining strengths. In the shadow of the Carpathians, beneath watchful Roman walls, the empire forged a new province, ensuring that its victories endured not just in marble reliefs, but in the living bones of the land itself.