Introduction: An Emperor’s Final March

In 208 AD, the Roman Empire stretched from the deserts of Africa to the misty highlands of northern Britain. At its helm stood Septimius Severus, a North African-born emperor whose ambition, ruthlessness, and military prowess had shaped a new imperial dynasty. But as he neared the end of his reign, Severus sought to leave one last mark: the total subjugation of northern Britain. His campaign beyond Hadrian’s Wall would be Rome’s final great military push in the British Isles—and a somber epilogue to a life of conquest.

The State of Roman Britain

By the late 2nd century, Roman control in Britain was fracturing. While the southern regions remained pacified, the north—home to fierce tribes such as the Caledonians and Maeatae—remained volatile. Hadrian’s Wall, built nearly a century earlier, had long served as a defensive boundary, but Roman governors struggled to maintain stability beyond it. In 208 AD, Severus crossed the Channel with a massive force, determined to reassert Roman power and bring permanent peace to the island’s wild frontiers.

Severus: Soldier and Strategist

Septimius Severus rose to power in 193 AD amid civil war and chaos. A seasoned general, he swiftly consolidated authority, crushed rivals, and established the Severan dynasty. Though often harsh, his reign brought reforms, urban development, and stronger central governance. Yet Severus remained ever the soldier-emperor, and when Britain faltered, he resolved to lead its conquest personally—despite his advanced age and failing health.

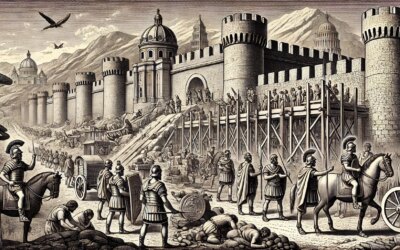

The British Campaign Begins

Landing in Britain with his sons Caracalla and Geta, Severus moved north in 208 AD with an army estimated at over 40,000 men. He established headquarters in Eboracum (modern York) and launched a systematic campaign into Caledonia. Roman forces rebuilt and reinforced forts along Hadrian’s Wall and pushed deep into enemy territory, constructing roads and supply lines across treacherous terrain. Yet the tribes avoided open battle, retreating into forests and mountains while harassing Roman troops with guerrilla tactics.

A Campaign of Attrition

Severus’s campaign was relentless and brutal. Ancient sources describe scorched earth tactics, mass slaughter, and the construction of punitive infrastructure. The Caledonians were slowly worn down, but Roman losses were heavy, and the gains proved fragile. In 210 AD, the emperor suffered a severe illness, possibly gout or arthritis, which left him immobile. Despite this, he continued to direct the campaign, famously declaring, “Let no one ever again speak of peace while I live—only of war.”

Death in Eboracum

In early 211 AD, Septimius Severus died in Eboracum. He was 65. His body was cremated and his ashes returned to Rome. His death ended the campaign, and his sons—particularly Caracalla—soon lost interest in continuing it. The Romans withdrew to Hadrian’s Wall, abandoning further efforts to conquer the highlands. The empire had reached its northernmost limit in Britain, and it would never push further.

Legacy of the British Expedition

Though the campaign failed to fully subdue northern Britain, it left a mark. Roman presence in the north was strengthened for a time, and the infrastructure built by Severus endured. His visit also symbolized the reach of Roman power and the emperor’s commitment to defending even the most remote provinces. Severus’s final act was one of duty, discipline, and defiance against old age and insurgency alike.

Conclusion: The Last Legion

Septimius Severus’s march into Britain in 208 AD was not merely a military operation—it was a statement. In the twilight of his life, he reminded the world that Rome remained a force to be reckoned with. Though his conquest was incomplete, the memory of his campaign endured, etched into the misty hills and fortified stones of Hadrian’s Wall. He died as he had lived—on campaign, in armor, in command.